Biden’s hugely consequential high-tech export ban on China, explained by an expert

An employee works on the production line of semiconductors at a factory in Huai’an, China, on September 27. | VCG/VCG via Getty ImagesThe ban on semiconductor exports to China is one of the most important policy moves of the...

One month ago, the US Commerce Department issued an exceptionally broad set of prohibitions on exports to China of semiconductor chips and other high-tech equipment.

The very technical nature of the export controls might obscure just how consequential this new policy could be — perhaps among the most important of this administration.

The new rules appear to mark a major shift in the Biden administration’s China strategy, and present a substantial threat to high-tech industries in China, including military technology and artificial intelligence. Washington think tank CSIS called the White House’s new approach to the Chinese tech sector “strangling with an intent to kill.” A Chinese American tech entrepreneur tweeted that China’s chip businesses fear “annihilation” and “industry-wide decapitation.”

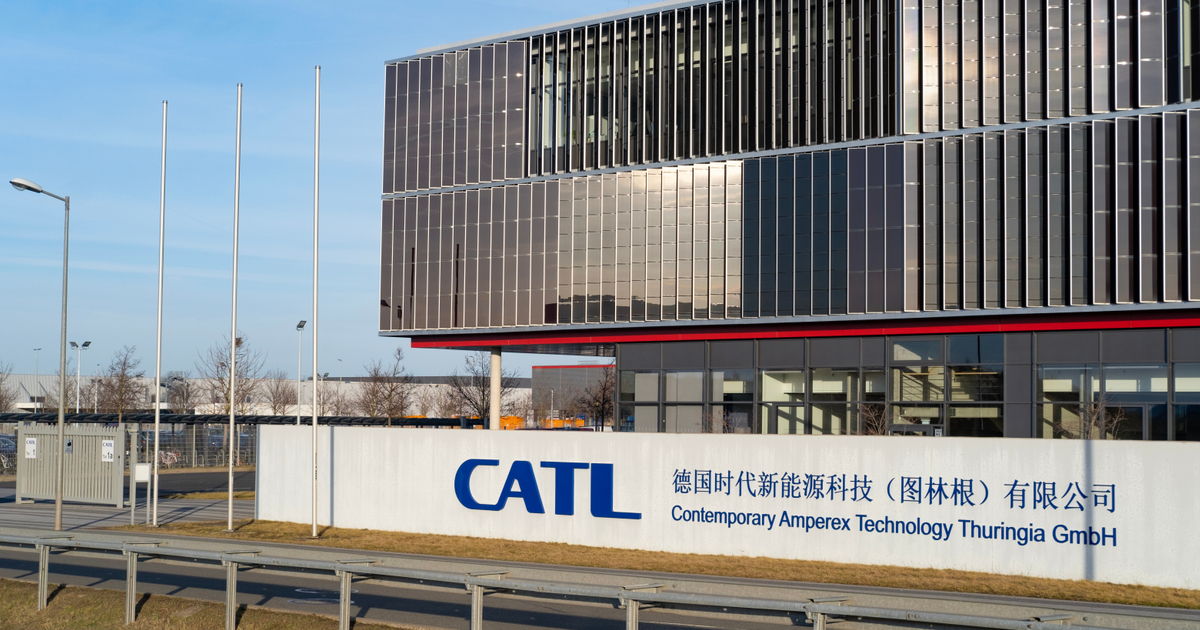

Dominance across cutting-edge technologies has long been a centerpiece of Beijing’s vision for the country’s future. China can already compete with industry leaders across a range of leading-edge technologies, but global semiconductor production is still dominated by a few corporations, none of them Chinese. China is dependent on foreign chips; the country spends more per year importing chips than oil.

But the new export controls ban the export to China of cutting-edge chips, as well as chip design software, chip manufacturing equipment, and US-built components of manufacturing equipment. Not only do the prohibitions cover exports from American firms, but also apply to any company worldwide that uses US semiconductor technology — which would cover all the world’s leading chipmakers. The new rules also forbid US citizens, residents, and green-card holders from working in Chinese chip firms.

In short, the Biden administration wants to prevent China from buying the world’s best chips and the machines to make them. These top chips will power not only the next generations of military and AI technologies, but also self-driving vehicles and the surveillance tech that Beijing relies on to monitor its citizens.

What are the stakes of the Biden administration’s move? How will China respond? Where does this geopolitical drama go next? To find out, I spoke with Jordan Schneider, a senior analyst for China and technology at the Rhodium Group, a research firm. A transcript of our conversation follows, edited for length and clarity.

Michael Bluhm

What is the Biden administration hoping to achieve with these export controls?

Jordan Schneider

In a speech in September, National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan gave a new justification for US thinking about export controls of emerging technologies in China. He made the case that certain technologies are “force multipliers,” and so important to future economic and national security eventualities that the US needs to do whatever it can to increase the gap between American and Chinese capabilities.

Because of that, you now see these path-breaking and very aggressive tech controls on semiconductors. The goal is to maintain, for certain foundational technologies, as large a lead as possible for the rest of the world ahead of China.

Michael Bluhm

Observers in both the US and China have said that this is a tremendously important move by the Biden administration, for both technology and geopolitics. How big of a deal is this?

Jordan Schneider

It’s a big deal for the Chinese semiconductor industry. It’s a big deal for the global semiconductor industry. When you’re weighing its importance in the entirety of US policy, it is a relatively niche thing, but it’s important because it’s an inflection point.

It’s the first manifestation of this new doctrine that Jake Sullivan put forward, and it’s likely to play out across a number of different technologies. Alan Estevez, the undersecretary of commerce who leads the Commerce Department’s Bureau of Industry and Security, said in late October that the US is not necessarily going to stop at semiconductors. They’re going to go down the list of the potential, emerging technologies that will define the next few decades of the global economic and technological landscape, and then figure out what the US can do to try to constrain domestic Chinese capabilities.

The export controls are an important fulcrum for a number of reasons. First, during these first two years of the Biden administration, it wasn’t clear that they would land where they did: taking much more aggressive steps to constrain Chinese technological development.

Second, it’s a milestone on a very long arc. In the early 1980s, the US was trying to boost Chinese technology, to balance against the Soviet Union. We brought China into the World Trade Organization. And now, the conclusion by a centrist Democrat president — which would be ramped up and amplified if a Republican took office — is that China can’t be trusted with frontier tech.

That’s because of China’s place in the world, and in particular because of the centrality of civil-military fusion in [Chinese President Xi Jinping’s] vision — the idea that the Chinese state is hoping to use civilian companies to directly increase Chinese military capabilities.

The restrictions are a very dramatic decision by the Biden administration, and if US-China competition weren’t already baked in, this is really a point of no return for the relationship.

Michael Bluhm

This seems like a dramatic geopolitical moment. And this relationship, at least according to some analysts, might define global politics in the 21st century. How might the export controls affect dynamics between the US and China?

Jordan Schneider

It’s important to recognize that this is a dynamic environment. The Chinese government will have its say, too. With the Chinese Communist Party’s recent Party Congress, we had a dramatic manifestation of just how much Xi has consolidated power and how his vision of China’s future will dominate the People’s Republic for years.

The Biden administration spent its first two years saying to China, “Let’s do some stuff on climate change. Maybe we can collaborate on some public-health issues.” Time after time, the Chinese government has just not been interested in pursuing the positive-sum activities that the Biden administration came in thinking that it might be able to pursue.

The Biden administration would have liked a slightly more even balance between the competitive, collaborative, and adversarial parts of the US-China relationship, but that’s not where Xi wants to take it.

The administration has come to the conclusion that the types of collaboration that Xi is particularly interested in — such as the transfer to China of foreign technologies — doesn’t play to the US advantage in the long term. There’s a completely merited lack of trust, in the Biden administration, for where Xi wants to take China.

Michael Bluhm

You began your answer by making the point that China has agency here, too— and by noting Xi’s increasing political dominance. So how are China’s leaders responding to the export controls?

Jordan Schneider

We haven’t heard a lot in the past few weeks, for understandable reasons. The Party Congress is the largest political event every five years, and it definitely led to less decision-making bandwidth for senior leaders.

Given some recent reporting from Bloomberg about a conversation that officials from China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology had with senior executives in the Chinese semiconductor industry, it seems like they’re still processing what this means for the future of their industry. They will soon find, if they haven’t already, that this is a really devastating blow for the future of Chinese firms trying to develop frontier tech in the chip space.

They have a number of potential paths ahead. They could double down on manufacturing lagging-edge tech, which means well-established technologies that are still widely used in countless products. They could try to punish the US by retaliating against leading electronics firms. They could retaliate directly against the semiconductor supply chain by making moves on the rare earth minerals necessary to make chips, or on packaging — areas where China has a considerable place in the global market. They could do something as escalatory as a cyber-attack on some leading-edge American chipmaker.

Given how core this vision of creating a self-reliant tech ecosystem is to China’s leaders, I don’t think they’re going to look at these export controls and say, “Okay, maybe we should give up and focus somewhere else.” The long-term goal of creating leading-edge capacity in China has been such a core part of Xi’s vision that I find it hard to imagine them not taking this as a challenge.

Michael Bluhm

Building a cutting-edge tech industry is a critical part of Xi’s strategy, as you say, but the US is also working to move some chip manufacturing onshore. The pandemic made clear to many in both parties that the US was dependent on fragile supply chains for many of the most critical technologies.

The CHIPS Act passed in July with bipartisan support in the Senate, and it aims to support research and production of semiconductor chips in America. But how realistic is it to build a substantial chip manufacturing industry in the United States?

Jordan Schneider

It’s definitely realistic. For a long time, America manufactured most of these chips. It’s unrealistic to do what China is now going to have to do: create leading-edge chips in China by localizing thousands of different steps in the supply chain.

The CHIPS Act and the broader push to restore semiconductor fabrication to the US has a number of different aims. The Commerce Department outlined four goals in its strategy document: to invest in American production of strategically important chips, particularly leading-edge chips; to make the global supply chain more sustainable, particularly for national security purposes; to support American R&D; and make the American semiconductor workforce more diverse and vibrant.

Those aims are achievable, though it’s unclear whether the funding in the act is going to be enough. Given the worries about potential disruption of chip manufacturing in Taiwan, this is a bit of an insurance policy for any eventuality there.

There is also a broader justification in industrial strategy, because this is and will continue to be one of the most important industries. Without this support, it’s unlikely that much new semiconductor fabrication capacity would come online at all within the US, because it’s competing against Taiwan, Singapore, Japan, China, and South Korea, all of which subsidize domestic manufacturers.

Michael Bluhm

In the end, how seriously do you think this could damage the Chinese high-tech industry?

Jordan Schneider

This is essentially freezing in place the level to which these Chinese fabrication firms have advanced today. There’s a ton of fabrication capacity in lagging-edge tech in China. They’ll be able to continue business as usual, making hundreds of millions of chips that go into electronics sold all over the world. But they won’t be able to make the highest-end, highest performance, most power-efficient chips, which the US government has identified as being important — particularly for WMD, but also in the coming artificial intelligence revolution. These are the chips that are going to be running the AI models that are going to shape our lives militarily and economically.

The advancement that you would expect Chinese firms to make is now largely closed off to them. The international technology and suppliers that they would need to advance to where Intel, TSMC, and Samsung currently are, is now blocked off to them, thanks to these new regulations.

Michael Bluhm is a senior editor at The Signal. He was previously the managing editor at the Open Markets Institute and a writer and editor for the Daily Star in Beirut.

Hollif

Hollif