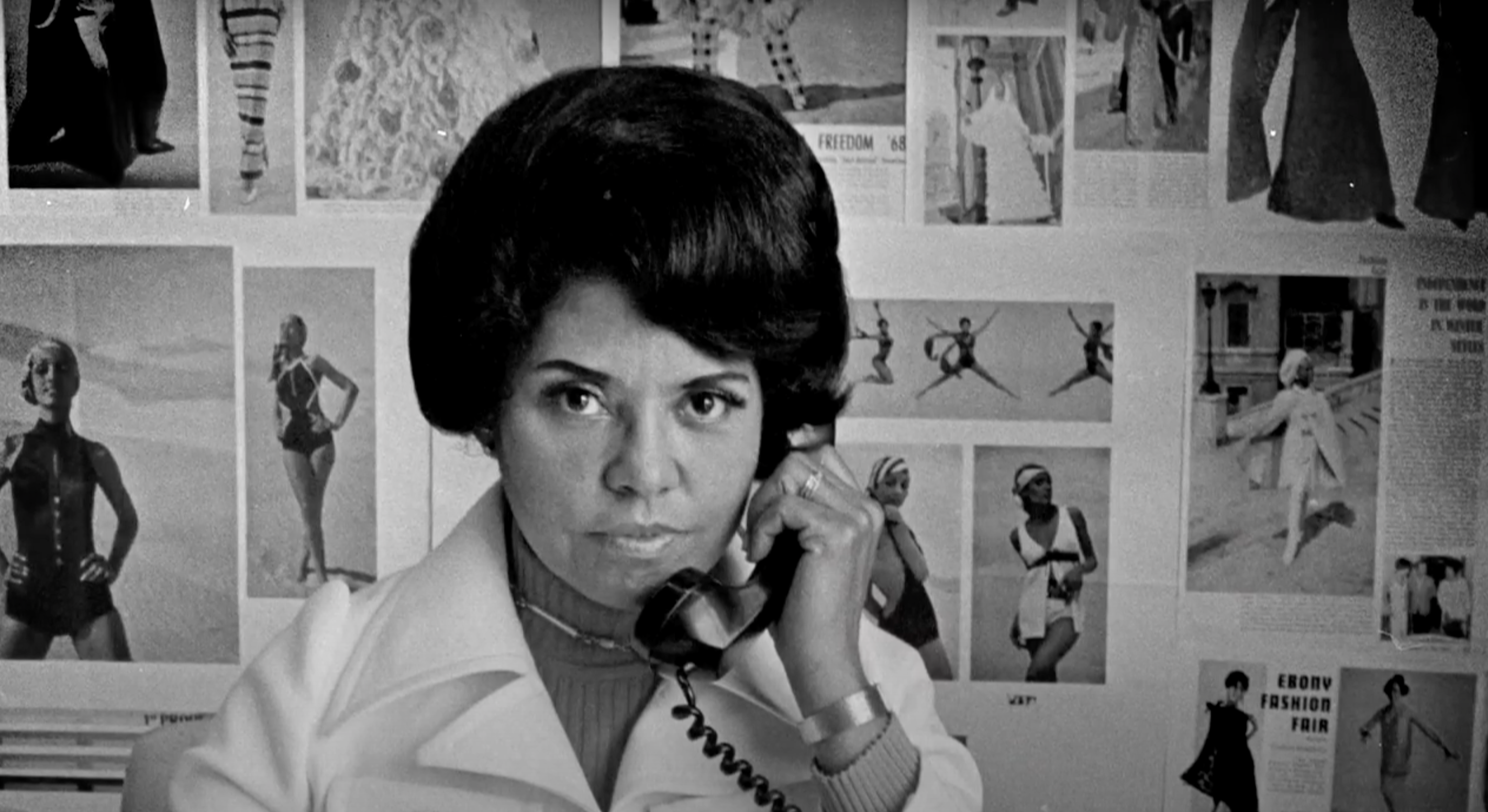

DOC NYC 2022 Women Directors: Meet Fatimah Dadzie – “Fati’s Choice”

As a filmmaker, Fatimah Dadzie’s forte is in telling compelling stories about marginalized groups. She previously directed “success stories,” about the reproductive health of adolescent girls. “Fati’s choice” is her first documentary film. It was awarded best feature film...

As a filmmaker, Fatimah Dadzie’s forte is in telling compelling stories about marginalized groups. She previously directed “success stories,” about the reproductive health of adolescent girls. “Fati’s choice” is her first documentary film. It was awarded best feature film at the 2021 Global Migration Film Festival and won the Audience Award at the 2022 Filmfest Eberswalde Provinziale.

“Fati’s Choice” is screening at the 2022 DOC NYC film festival, which is running from November 9-27.

W&H: Describe the film for us in your own words.

FD: Fati didn’t want to go to Europe — it was her husband’s dream. Unemployed, the TV repairman left their village in Ghana but didn’t make it any further than Libya. He was arrested in Tripoli, where he asked Fati to join him. She went, and when she fell pregnant, the couple decided to make one last bid at reaching the West.

They made it to Italy but were sent to a migrant camp. It was there that Fati broke. She asked to be repatriated but paid a heavy price: her husband divorced her and her community considers her a failure. But Fati wants to provide for her family, even though she still has to liberate three of her children from the custody of her in-laws.

“Fati’s Choice” explores the stigma associated with returnees and how such societal judgment contributes to irregular migration.

W&H: What drew you to this story?

FD: Growing up, many people in my community traveled abroad and never returned home. The fear of being labeled a failure was one of several reasons that prevented them from returning. Additionally, those who made it home had to go to extra lengths to impress family, friends, and even the whole community to be recognized as successful, earning themselves the name “Been Tos.” I wanted to dig deeper into this phenomenon to understand why people feel the need to travel to Europe to succeed. Is it due to our colonial past, which causes everything Western to be perceived as good?

But most importantly, I saw the perfect protagonist in Fati because she stood out as a woman who cherished her independence, made personal decisions, and stood by them, irrespective of the consequences. I was inspired by her story, especially the bold decision to return home regardless of the inevitable stigma and criticisms that she will face.

W&H: What do you want people to think about after they watch the film?

FD: I want the audience to reflect on the issues raised in the film, especially the difficult choice Fati had to make for her children’s wellbeing. To Fati, the love she has for her children supersedes the unrealistic expectations in Europe.

W&H: What was the biggest challenge in making the film?

FD: Getting the protagonist, Fati, to agree to participate was a big challenge. She was skeptical about how she would be represented, afraid that I would be judgmental of her decision, like most people have been, and refused to be on camera. But as a filmmaker, I helped her understand my intention to tell stories of people with exceptional experiences, stories that could change public perceptions and even government policies.

It took about six months of convincing that her story is important and inspiring before Fati decided to share it with the world.

W&H: How did you get your film funded? Share some insights into how you got the film made.

FD: STEPS, a Cape Town-based non-profit media company specializing in documentary filmmaking, was seeking African filmmakers to tell stories about migration. I forwarded my idea and was selected for a story development workshop. My project was later considered for further funding through a series of subsequent production workshops. All this was made possible by the DW Akademie.

W&H: What inspired you to become a filmmaker?

FD: I started my career in TV as a promotions producer and then moved to TV content licensing. I got inspired to venture into filmmaking when I had the opportunity to produce and direct “success stories,” an NGO documentary film on the adolescent and reproductive health of girls in the remotest parts of my country.

The voices of the underrepresented touched me in so many ways. It was then that I began to appreciate the power of film and the change that storytelling can bring to a society.

W&H: What’s the best and worst advice you’ve received?

FD: The best advice I have received was to go independent as a filmmaker. It was a huge risk at that time, considering how the freelance landscape in Ghana doesn’t provide any job security. But I’m happy I made the decision to go independent because I’m now doing what I’m most passionate about.

Worst advice? I was advised to pursue law because my high school results were apparently “too good” for me to pursue arts. During the time I was growing up, the arts were seen as a discipline pursued by non-achievers. Things are gradually changing as people are now becoming more exposed to the prospects of creative careers.

W&H: What advice do you have for other women directors?

FD: I was not taken seriously as a filmmaker. I was even told that my work was considered only because I am a woman, not because of what I want to tell the world, as if what I have to say is less important than my identity as a woman.

That said, I would advise fellow women in film to be confident in their professional capabilities and be assertive in their roles as filmmakers with something to contribute to society. Do not let others patronize you simply because you are a woman.

W&H: Name your favorite woman-directed film and why.

FD: “Buddha in Africa,” a documentary film directed by Nicole Schafer. The issue of colonialism is sensitive and rarely discussed in Africa. Unfortunately, we often see it rearing its ugly head again in a different form but seem to be unaware of it. However, Nicole captures this reemergence in a way that exposes our political systems and the loopholes that provide a fertile ground for this issue to fester.

Aside from the issues that it raises, “Buddha in Africa” was beautifully filmed and the storytelling is top notch.

W&H: What, if any, responsibilities do you think storytellers have to confront the tumult in the world, from the pandemic to the loss of abortion rights and systemic violence?

FD: It is the responsibility of storytellers to present diverse perspectives of issues our society is facing. There are different sides to every issue and stories must reflect that.

W&H: The film industry has a long history of underrepresenting people of color onscreen and behind the scenes and reinforcing – and creating – negative stereotypes. What actions do you think need to be taken to make Hollywood and/or the doc world more inclusive?

FD: We must have more filmmakers from diverse backgrounds telling stories from their unique perspectives and bringing fresh angles to even seemingly exhausted themes and topics. On the other hand, established writers and directors must, as a matter of urgency, explore and understand underrepresented stories and apply new approaches to represent them appropriately.

AbJimroe

AbJimroe