Freedom Is a Small-Town Gay Bar on Christmas Eve

On Tilopa's Six Nails, letting go, and going no-contact The post Freedom Is a Small-Town Gay Bar on Christmas Eve appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

On Tilopa’s Six Nails, letting go, and going no-contact

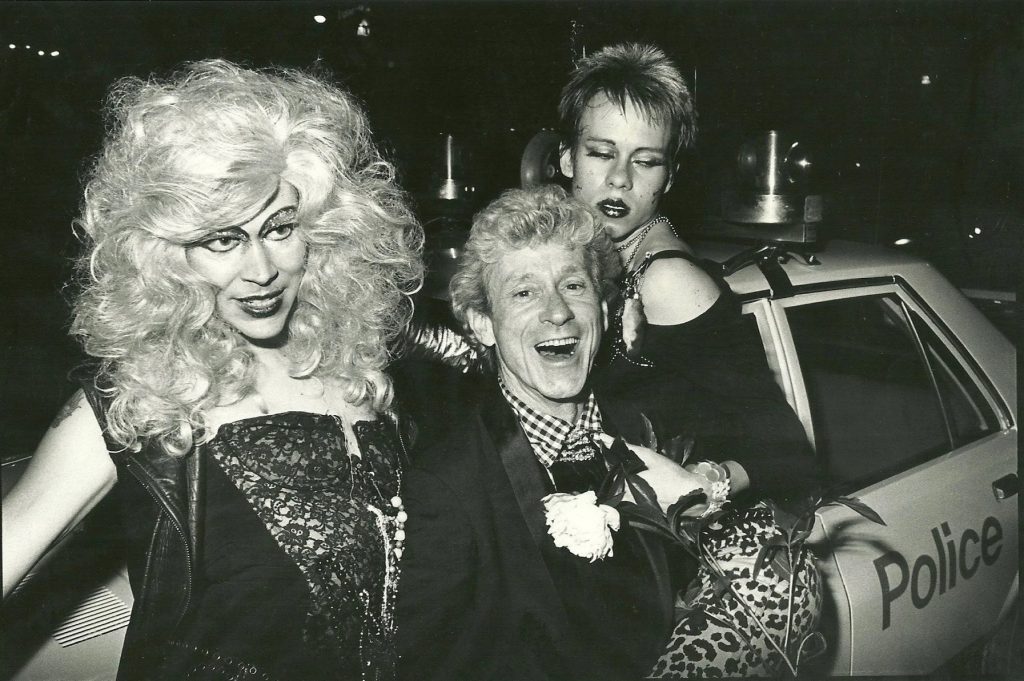

By Sarah Kokernot Dec 24, 2025 Legendary artist and queer Kentuckian, Henry Faulkner (middle), on what appears to be a very fun night in Lexington. | Image courtesy Faulkner Morgan Archive.

Legendary artist and queer Kentuckian, Henry Faulkner (middle), on what appears to be a very fun night in Lexington. | Image courtesy Faulkner Morgan Archive.

I don’t know if you’ve ever gone to a small-town gay bar on Christmas Eve. If you have, you likely ended up there because there was nowhere else to go that night.

I was back home for Christmas in Lexington, Kentucky, where I’d grown up and went to college. My partner just asked me to marry him in a snowy arboretum filled with fat robins dining on red holly berries. We returned home to tell my family it was official: we were getting married. But something wasn’t right.

One of my parents berated me for two hours in the living room. I listened to them tell me how selfish I was. Not just then, but since adolescence, the time that I started to become my own person. This parent struggles with severe, untreated mental illness. They had been verbally abusive to me and to my other parent for a while, but this was one of the first nights of many that I would experience them becoming so aggressive and cruel.

My partner sat on the couch in the back of the house, listening. When it was over we walked together outside to the driveway. He stopped and looked at me, astonished. He clearly wasn’t expecting that reaction from my parent.

We can leave right now and never come back if you want, he told me.

He didn’t understand that being berated by someone who was supposed to love me felt normal. I was upset, but I couldn’t leave. And I would never leave. I was their daughter and it was my job to stay no matter what they said or did.

*

In meditation and spiritual practice, we are often instructed to let go. To rest, to surrender, to allow. In the first three of The Six Nails by Tilopa, translated by Ken McLeod, we are told:

“Don’t recall. Let go of what has passed.

Don’t imagine. Let go of what may come.

Don’t think. Let go of what is happening now.”

Tilopa does not tell us what will happen when we let go. It’s as though he loves a good surprise, or that he hates to give away the ending. I can understand why he’s a bit secretive. Or why he wants us to figure it out on our own.

Still, I think it’s helpful to consider the question, What happens when we let go? The answer varies from person to person. This is what I’ve found to be true for myself.

*

I couldn’t let go, but I needed some space that Christmas Eve.

The one place I knew that would be open was The Bar, called so as a matter of discretion back in the early 1960’s when it was co-owned by Rock Hudson. For decades, heavy curtains covered the front windows so no one could see who was inside. I had my twenty-first birthday there as a college student. During that time, in the aughts, there was no sign on the front door advertising its name. Only the thudding bass on a Saturday night would hint that there was anything interesting happening inside.

My partner and I waited in the car for a moment before going in. I looked in the mirror to see if it looked like I’d been crying. It did.

We waited a while longer. Then we walked across the icy street and opened the doors.

Across the room, the bartender looked up at me. In his gaze shone a look of deep recognition. He didn’t need to know my story to understand why I was there. Even now when I recall him looking at me, something melts in my shoulders. It’s incredible what a simple look of compassion can do for us. I could see myself better because he saw me. It wasn’t true, what my parent said. There was goodness in me. I didn’t deserve to be treated that way. No one does.

I wanted something warm. The bartender poured a decaf coffee with Bailey’s, on the house.

*

Beneath the discomfort of letting go is a fear of uncertainty.

Beneath the discomfort of letting go is a fear of uncertainty. When we can’t let go, we stay toxically attached or toxically hopeful. When we let go, we also let go of the familiar. We lose even the comfort of familiar pain. Without the familiar we walk into the vast unknown, into a spaciousness that can at first feel overwhelming. We can only take our curiosity with us.

What’s there?

*

It would take me fifteen years to decide to finally go no-contact with the parent who was abusive to me. Nothing I did could ever persuade them to get help. I had tried everything and I had read every book. I went to ask a therapist how I could communicate better with my parent. How I could talk in a way that would calm them down and make them understand they were hurting me. My therapist told me I was suffering from anxiety and PTSD from being exposed to repeated verbal and emotional abuse. But I wouldn’t leave. I hoped my parent would get better. Surely there was something I could do.

There wasn’t.

It was the hardest decision I’ve ever made. There was no changing them. There was no saving them. I had to let go.

*

It’s been a year since I broke things off. Going no-contact with my abusive parent was the greatest act of self-love that I’ve ever given myself.

The only way I was able to leave was by letting go of all that I thought was me. My childhood home, the mementos from my beloved deceased parent, the vacation souvenirs and treasured possessions from my grandparents, the farm I would have inherited, the albums of photos, and most of all, the relationship with a person who has known me since my heart started to beat. Who at one point in my life, had not been a terrible parent. At one point they had been well enough to love me in a way that didn’t feel awful. I would trade everything I own for a parent who loves me unconditionally and in a way that doesn’t hurt. But that is not possible.

I was able to let go because I listened to Tilopa’s advice.

Over and over again, through hours upon hours of meditation, I practiced letting go.

With my other parent deceased, and my extended family broken and estranged, I often feel like an orphan from my own past, my own childhood, my own personal history.

But when I let go, I discover a state of being that feels as vivid as a physical place, where it is boundless and warm and constant. Inside us there’s a home that never changes. A constancy of love and compassion from which we’ll never be exiled. It took me years to find it. Once you find it, you know you belong there. Even in the moments when all seems lost, it’s still there.

Resting in this state of being reminds me of that small-town gay bar on Christmas Eve. When everything else is shut, this place is open. It welcomes those who are banished from their homes. It doesn’t care who you are. When I can relax in that place of acceptance, it feels like someone is always there, gazing at me with compassion and warmth. I don’t have to tell them my story to feel understood. When they see me I see myself.

*

The holidays can be a real bastard for so many of us. If that’s you, dear reader, I hope that you can feel your own awakened heart—or the universe, or God, or the ancestors, or the mystery—and feel yourself being seen, and know the seer is also you.

I hope you know you belong here.

♦

Originally published on Sarah Kokernot’s Substack. Reprinted with permission.

![]()

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.

This article is only for Subscribers!

Subscribe now to read this article and get immediate access to everything else.

Already a subscriber? Log in.

Lynk

Lynk