Her Gaze

Poet Li-Young Lee on his mother, the first mystery The post Her Gaze appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

Poet Li-Young Lee on his mother, the first mystery

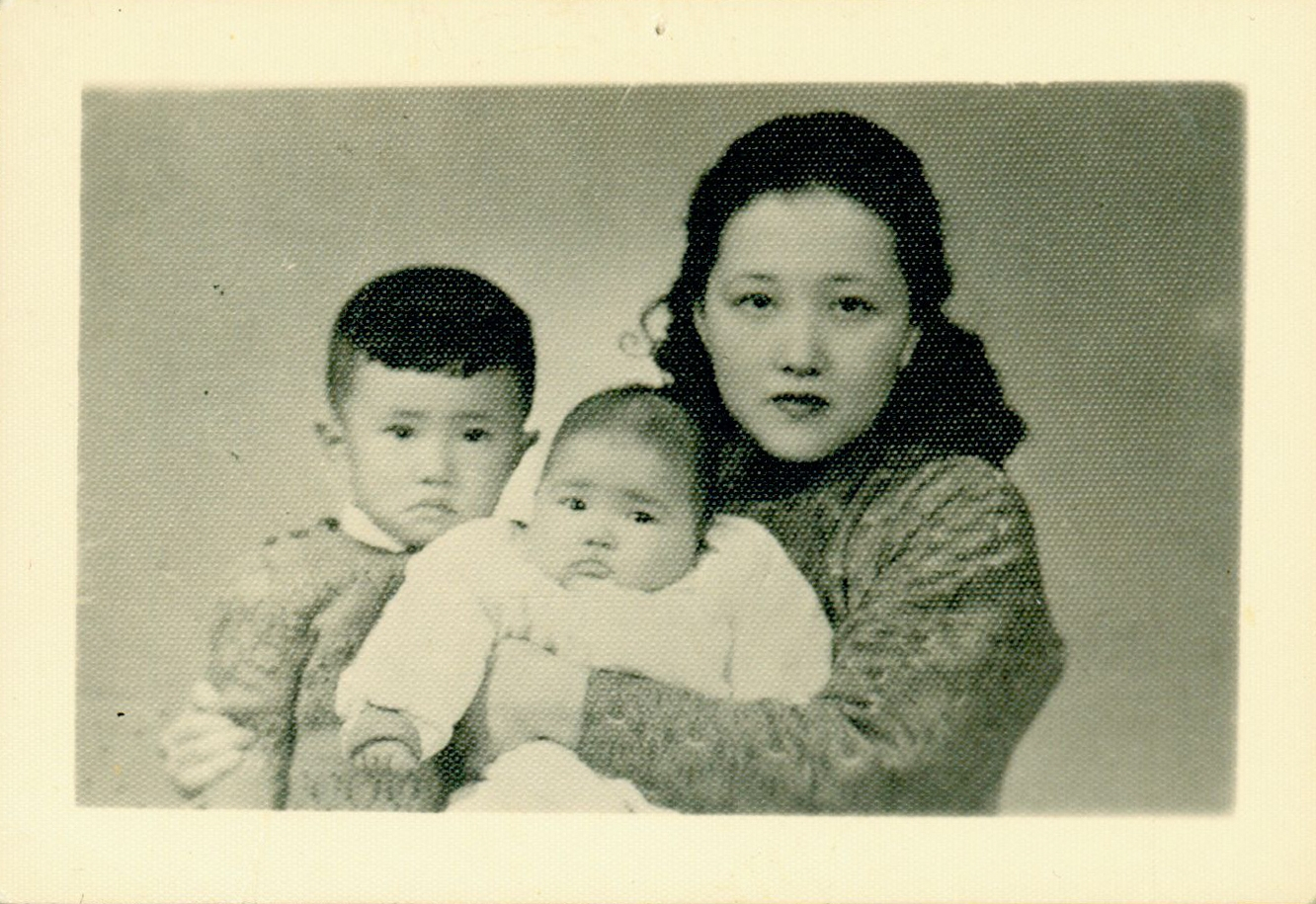

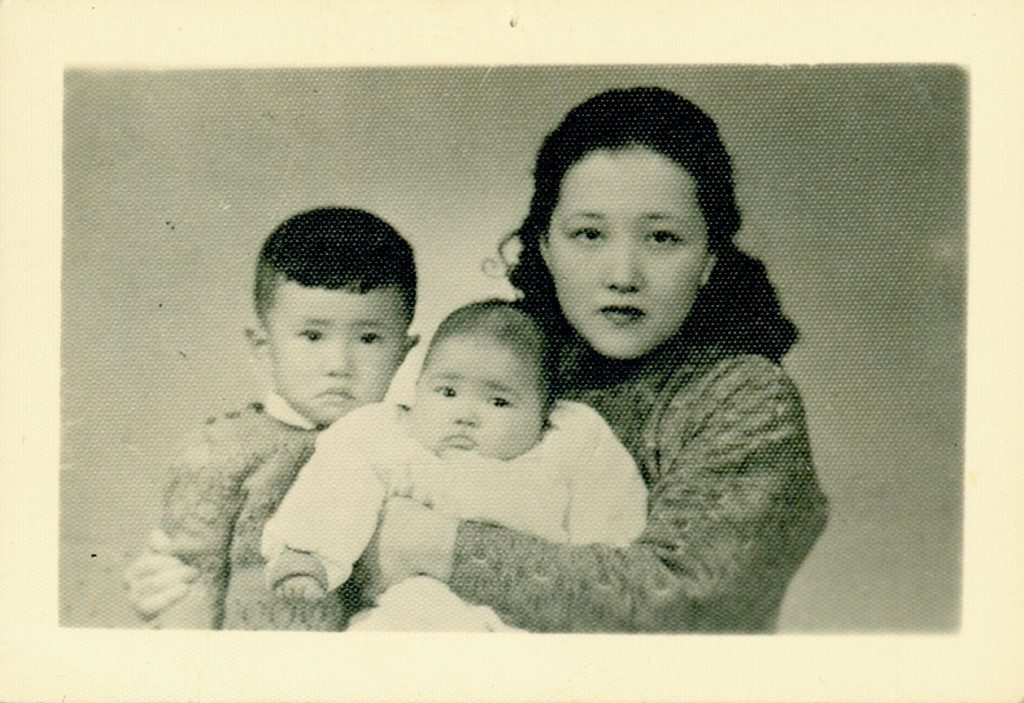

By Li-Young Lee, edited by Oliver Egger Dec 26, 2025 Li-Young Lee (middle) with his older brother and mother. | Photo courtesy Li-Young Lee.

Li-Young Lee (middle) with his older brother and mother. | Photo courtesy Li-Young Lee.

The following is a composite of perspectives from two interviews with Li-Young Lee conducted by Oliver Egger.

It’s impossible for me to talk about my mother. She comes before everything, before words, before the world, and before words for the world. Before syntax.

My mother is difficult to think about and to talk about because she was one of the most mysterious people I’ve ever met. She means so many things to me and at so many levels, at so many scales, in so many dimensions, that I feel eternally as if I’m her subject. I’m second person to her first personhood, somehow.

She saw me before I saw her. And she taught me to pray. And she reminded me all the time to pray. She said, “Only pray. Nothing else makes sense, just pray.” And what is prayer? I’ve been asking my whole life.

There is an inner room in me, and I think my mother either helped me build that room, or I inherited it from her. One of the early introductions to this inner room was when, as a child, I found her crying to herself. By allowing me into her grief, I found this inner room inside myself.

All of my sentence patterns more than likely have imprinted upon them the patterns she pressed into my very body and soul while I lay inside her, growing, listening, a pattern growing inside of her patterns of happiness and sadness, hope and despair, hunger and satiety, waking, dreaming, or sleeping, love and fear. For all I know, her face lies behind every face I see. My mother’s face is the first face. She is the first voice. The face and the voice before everything. I can’t contemplate what comes before everything. That’s like thinking about God. That’s impossible.

But Poetry is impossible. Poetry is impossible because poetry is thinking which contemplates its own source, words spoken within hearing of their precondition: silence. Poetry is words which find their source not in other words but in human listening and its silence. And that’s why we who practice poetry continually practice turning a line back to the beginning. Writing poetry is impossible. Thinking about poetry is impossible. Two impossibles: poetry and my mother. I have my beginning in both. Syntax and mother, both come before the world. Poetry made the world. Poetry is the language of creation. Poetry is the language of ultimate reality. Poetic logic is the logic of creation, the logic of God, the logic of ecstasy, since ecstasy is that process by which any phenomenon emerges, by which any and all worlds are manifest. Poetry is in the world but not of the world. Poetry makes the world.

Poetry is words which find their source not in other words but in human listening and its silence. And that’s why we who practice poetry continually practice turning a line back to the beginning.

My mother never assimilated. She never quite learned English. She learned enough just to get her through to about the age of 60. And then she totally just gave up and spoke very little English. And before that, she spoke very halting English. She spoke only Chinese with us. She wanted to ensure that we spoke our Chinese. She was a symbol for me, a living symbol of old China and of the inner world of family. The family was Chinese. And because of that, America remained outside. America always felt like it was not quite home.

So many things that happened to her, terrible things just happened to her. Things like a mob coming to her house and destroying it. She wasn’t going to have a say there. She wasn’t going to put her foot down and go, “OK, I’m asserting my power.” No, no, no, no. You’re going to say, “How small can I make myself so I don’t get in the way?”

I keep thinking about the nature of the mother, and I keep thinking that she was a perfect mother if that means she was the bearer of all things. She literally bore all things. And the nature of that is the same as how to make a poem. The poem is a receptacle of consciousness and unconsciousness. So, it’s a maternal practice, and it’s a practice of the mind and the mind retiring and nursing.

Home was where my mother’s audience began. And I grew up in her audience. She had a very loving, very capacious, and very blank audience that allowed for a lot. She was a very tolerant, very loving, and very private woman. And this privacy she instilled in me.

In the beginning was poetry. And without poetry, there is neither cosmos nor world, and certainly no person or persons. No figures, no mother, no son.

There was a bipolarity to her. She went from a total sanctification, intelligence, and understanding to just total grief and despair. There’s a similar bipolarity in art, in the poem. The poem is an altar. This altar, traditionally, is the place a human being makes exchanges with the divine realms: the dead, the upper worlds, the lower worlds. That symbol of the altar to my mind, that’s what the blank page is, that’s what the horizon of the pages is. The poem invites the greatest contradictions and solves them without reducing any of the elements to some sort of incoherent soup. That, to me, is the great poem.

Poetry is the voice of ultimate experience and death. Poetry is the understanding of first and last things.

This idea of the inner room, the inner sanctum, the place for prayer, these are all feminine ideas. I think my mother set the terms in the same way that the feminine sets the terms in poetry. The way the sonnet sets the terms. Fourteen is a feminine number, directly related to the feminine body, and it was invented, legend has it, by a woman who set the terms for a male to fulfill during the times of the troubadours. This is prior to Petrarch, who stole it from the troubadours. So this idea that the feminine sets the terms is a founding principle of all myths and legends of the art forms that are deeply embedded in the structure of the lover and the beloved.

To think about my mother is to contemplate first things. First patterns. Cradles are made in her image. Poetry is the voice of infancy and the mind of innocence. But so are boats and entrances to temples and tombs made in her image. Poetry is the voice of ultimate experience and death. Poetry is the understanding of first and last things.

I never knew if I was trying to win my mother’s heart or God’s when I wrote poems.

There was always so much between us that was unclear. I wrote in order to clarify myself to her. I wanted her to see me clearly.

Her gaze on me and my gaze on her. I grew up in her gaze. That’s what I mean by her audience: her gaze. She had a beautiful gaze. And she had a beautiful “Amen.” She taught me how to pray.

When she was dying, I just crawled up onto her bed and didn’t leave for, what was it, a month, two months? I don’t even know how long. I should know. As she died, I just held her and held her and held her. And she kept confusing me for somebody else. My father. She turned into a baby. Her body was just riddled with bed sores. I was changing her bandages three or four times a day. But man, she was a beautiful, beautiful person.

♦

“Her Gaze” reprinted from I Ask My Mother To Sing: Mother Poems of Li-Young Lee, edited by Oliver Egger (Wesleyan University Press, 2025).

![]()

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.

This article is only for Subscribers!

Subscribe now to read this article and get immediate access to everything else.

Already a subscriber? Log in.

Astrong

Astrong