The 8 Things Stressing Americans Out the Most (and Some Hope for Each)

A recently published Harris Poll conducted on behalf of the American Psychological Association paints a bleak picture of a disaffected America. We’re disillusioned by government, see our nation as beset by violence and crime, and feel increasingly financially insecure....

Photo: Govorov Evgeny (Shutterstock)

A recently published Harris Poll conducted on behalf of the American Psychological Association paints a bleak picture of a disaffected America. We’re disillusioned by government, see our nation as beset by violence and crime, and feel increasingly financially insecure. In other words, everyone is stressed out; so stressed out that more than a quarter of us (27%) report we can’t function on most days.

There’s no denying the bleak national mood, but are our national fears reasonable? How much of our angst is a product of actual events, and how much comes of the distorted worldview provided by the funhouse mirrors of social media and the mass media?

Because I am a contrarian and an optimist (and maybe to make myself feel better), I’ve considered the eight things Americans are most likely to be stressed about according to the APA poll, and tried to find a reason each might not be as bad as they seem.

Inflation

Probably due to pandemic-related stimulus programs and a pandemic-related supply chain issues, inflation began increasing worldwide in 2021 and hasn’t’ let up since. No doubt Americans are are freaked out: learning that a thing you always buy is suddenly significantly more expensive is a jarring experience. But there is an upside to inflation, especially if you’re in debt.

You only have to pay back the number of dollars you borrowed, so if the value of each dollar decreases, your debt shrinks. It’s bad for your 401K, but great for your home or student loans. A couple weeks of Venezuelan style inflation and you could pay off your credit cards for the cost of a ham sandwich.

Of course, a 1,500% inflation rate would mean you had bigger problems than paying back some money you borrowed, but our current inflation is nowhere close at “only” 8%, and there’s reason to think that number has already peaked (though it will likely be a while before prices begin dropping).

Inflation is a result of too much money in the system, and when we want to lower inflation, the Federal Reserve Bank taps on the economy’s brakes by making money more expensive to borrow. The Fed has raised interest rates by a full three percentage points in the last six months. They’re relatively delicate on the pedal because raising interest rates too much, too fast can lead to recession, so we haven’t see dramatic effects yet, but according to some economists, including Paul Krugman, that’s only because of the lag between policy being enacted and its effects being realized. So more reasonable economic days are ahead. Maybe.

The future of our nation

According to the APA’s survey, 68% of respondents said this is “the lowest point in our nation’s history that they can remember.” It makes sense that people feel that way, but I don’t think it’s because this is a uniquely bad moment historically. It’s the opposite: In general, Americans have had it so good for so long, we can’t remember what actual bad times are like because we haven’t experienced any.

Imagine, for instance, you were born in 1900. As you turn 14 and are starting high school, the entire world is engaged in an all-out war that leaves 40 million people dead and lasts until you’re in college. About a decade later, when you’re in your early 20s, the U.S. economy slides into a state of ruin that is orders of magnitude worse than any recession any of us have experienced, and it lasts for 10 years. As you reach middle age, another, even worse World War breaks out. 50 million more people die, including nearly half a million Americans. Those are three worse moments, by far, than anything people are facing now, and you’ve experienced all of them before you turned 50.

Violence and crime

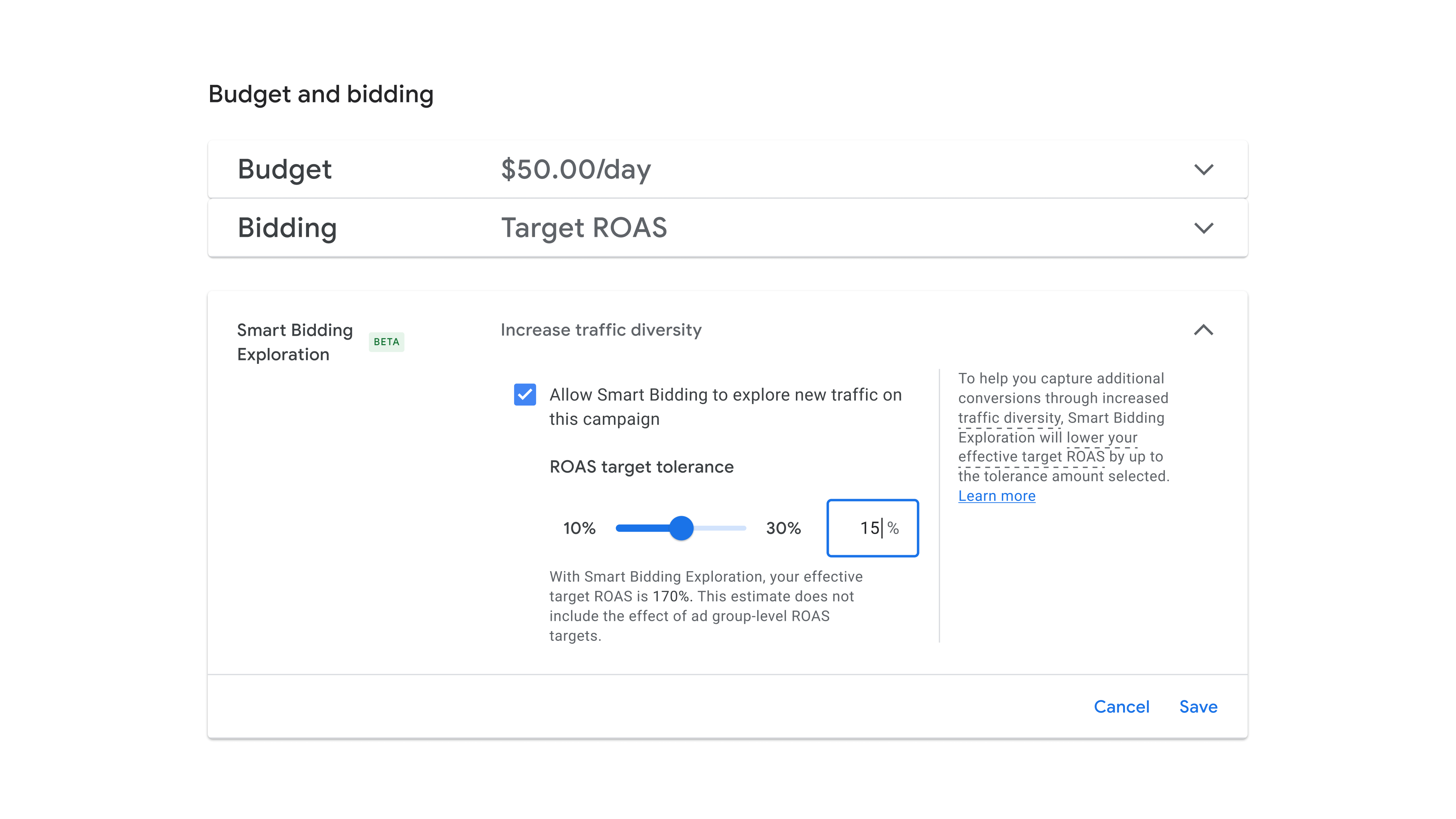

(U.S. Murder/Homicide Rate 1990-2022)

Violent crime increased by about 5% in 2020, and murders rose by 30% between 2019 and 2020, so it’s easy to see why people are concerned, especially given the year-over-year rise from 2019 to 2020, the highest one-year spike since we started counting. But if you leave aside the snapshot and look at the long view represented in the graph above, you can see that the total number of murders and other violent crimes is significantly lower than in the “good old days” of the 1990s.

We started from a historically low baseline of violent crime, which makes the leap seem substantial, but it looks more like a blip than the beginning of an upward trend. According to the FBI, violent crime was basically flat in 2021, which suggests this could be a “new normal.” It’s worse than recent years, but significantly better than 30 years ago.

Mass shootings

By most measures, mass shootings have risen steadily over the last 20 years, and there’s no real reason to think the trend will stop. Mass shootings are uniquely nightmarish for their randomness and pointlessness, so they loom very large in our consciousness as a very big problem that must be solved. But in terms of actual, personal danger, mass shootings are not really something to worry about. According to The Violence Project Mass Shooter Database, during the worst years of mass shootings thus far—that is, between 2017 and 2021—the horrific incidents killed a total of 295 people in the U.S. During that same period, around 300 people died of jellyfish stings and around 171,660 people died in car accidents. This is not to suggest that mass shootings don’t represent a major issue with regard to both our culture and need for legislative reform—just that you personally are statistically unlikely to experience one. (Sorry, that’s the best I can do with this one.)

Gun violence

Image: Public Domain

Speaking of guns, according to the CDC, gun related deaths are at their highest levels in 25 years. In 2020, 79% of all homicides and 53% of all suicides involved guns in the US.

Actually, I really can’t see anything positive about this. It’s just absolute madness and people should be completely stressed about it.

Healthcare

Of all the things stressing Americans out, healthcare is the most useful thing for us to worry over. Unlike nebulous ideas like “the direction of the country” or “increased global tension,” you can do something about healthcare, or at least do something about your own health—like eat better, exercise more, get enough sleep, and, ironically, try to avoid stress.

8 / 10

Increased global tension/conflict

Increased global tension/conflict

At the risk of sounding like a broken record, if you’re stressed about “global tension,” it’s probably because you’re not putting our current international situation in a broader historical context.

The world has been shifting away from armed conflict and toward diplomacy steadily since World War I. There were 77 times the number of international alliance agreements in place in 2012 compared to 1918, suggesting that diplomacy is growing much faster than armed conflict. We are no longer locked in a nuclear cold war with a competing empire. Battle deaths in the last 25 years make up only 3% of battle deaths in the last 100 years. In 1989, the number of democratic governments was larger than the number of autocracies for the first time in history.

9 / 10

The current political climate

The current political climate

It’s polarized out there, with both sides of the spectrum seemingly seeing the world from entirely different points-of-view, and seeming to grow more extreme with every passing election (or day). Most of us are building our opinions in the perpetual present of social media, where the loudest and most extreme voices are amplified most, outrage is monetized by design, and algorithms further divide us into seething, often armed, camps of insular true believers.

Yet there are indications we’re trying to move beyond the polarization we see online. Groups like Braver Angels, the People’s Supper, and More in Common are working to rebuild a sense of pluralism and shared purpose among Americans. Maybe more importantly, research shows that younger people are better at understanding and contextualizing the social media that is fanning the flames of division. People born between 1997 and 2012 are more likely to be skeptical of what they view online, less likely to share false information, and more likely to consciously “train” the algorithms that define their online experience. Overall, they’re not being fooled by the things that tricked older people. Kids today, am I right?

AbJimroe

AbJimroe

![How To Measure Topical Authority [In 2025] via @sejournal, @Kevin_Indig](https://www.searchenginejournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/kevin-indig-growth-memo-133.png)