Through Grief to Freedom: The Story of Krsha Gautami

The staggering losses of a nun whose tale appears in the Kshudrakavastu illuminates the power of shared suffering. The post Through Grief to Freedom: The Story of Krsha Gautami appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

The second installment in the series of women in the Vinaya (the division of the Buddhist canon that lays out the structure of monastic life), what follows is a retelling of a story recorded in the Kshudrakavastu, a scripture from the Vinaya of the Mulasarvastivada school of the Sanskrit tradition.

It’s the story of the nun Krsha Gautami, who survived a series of staggering personal losses, as well as horrific violence, in her life. Even after all of this, however, she went on to achieve states of great realization. (Note: There is no relation to Gautama Buddha, but Venerable Krsha will be familiar to readers of the Pali canon, where she’s referred to as Kisa Gautami.)

As it is told in Pali scripture, after losing her young son, Krsha Gautami begged the Buddha to restore him to life. By way of response, the Buddha gave her the famous instruction involving a mustard seed. As told in Sanskrit, her story is longer and her losses are greater. The story’s first half is this:

Before she was a nun, Krsha was a young woman married to the son of a close family friend. She had already borne one child, and as the time drew near for her to give birth to their second, they set out for her mother’s house. When Krsha went into labor early, her husband drew their chariot to the side of the road. Not knowing how to help her, he fell asleep beneath a tree, and Krsha gave birth alone in the chariot, their toddler son nearby.

Somehow pulling herself together soon after giving birth, she stepped out of the chariot and carried their newborn to where her husband lay—only to find that he had been bitten by a venomous snake in his sleep, and died. As Krsha stood weeping over his body with her infant and toddler in her arms, a thief made off with the horse that drew their chariot, stranding them.

At that moment, the sky filled with dark clouds and it started to rain. Water overtook the road with shocking swiftness. There was no choice but to wade through it.

“If I try to cross with the children,” she realized, with growing alarm, “all three of us will drown.”

Indeed the water was treacherous, and the two children together unwieldy. She left the toddler on the near bank, and waded across carrying the baby, who she set down on the far bank, then began doubling back for the other.

She was mid-river when a fox appeared. The water was high enough to prevent her from moving quickly. In the time it took her to turn around, the fox had snatched up the baby and carried it into the woods. Krsha froze, then began to leap up and down, waving her hands and crying out after the fox. The toddler, thinking she was calling him, stepped toward her, off the bank and into the water. He disappeared into the river. To her horror, Krsha was unable to save either one of them.

Husband and children torn from her, she was devastated. She stood on the riverbank in the middle of the wilderness, with nothing but a cloth wrapped around her lower body, and heard only the sound of the rushing water and the crying birds. She sobbed for her husband, for her toddler, and for the newborn. All but choking with tears of pity and compassion, with her hands she drew together a mound of earth.

Amid great hardship Krsha fights her way back to her family. Finally she arrives and finds that in the interim, her parents too had passed away. She was overcome by a second wave of traumatic grief. Her reflections appear in verse, in the manner of the sutras.

Why did I remain at home?

What profit did it bring me?

Husband, friends and family ripped away—

I shall go, for it makes no sense to linger.

Better to stay in the forest, alone,

Than to live in an empty house.

The household life is sin—of what use is it, then?

It multiplies our sorrows and suffering.

She goes off into the forest, intending to remain alone for the rest of her life. There she met a kindly older woman who invited her home. When Krsha had recovered enough, they began spinning thread together, eking out a living through shared labor.

Despite Krsha’s stated wish to remain alone, her elder friend pressed her to remarry—specifically, to marry a handsome young man who returned often to their house to buy thread.

“Daughter,” the elder woman said, “the young weaver asked after you. He has no wife. You should assent, and be happy.”

“Enough—never speak of this again,” the younger woman said. “I’m disenchanted with household life. Come what may, I’ll never live that way again.”

“Daughter,” said the elder, “a woman’s life is tenuous. We dwell in states of suffering. Such opportunities are rare. Reflect on our condition, give him your assent, and stay with him. If you don’t, it will be a mistake.”

Eventually Krsha relented, and on a suitable day, date, and time the young weaver took her into his house. But he was cruel…

In light of the extremely graphic violence that unfolds over the course of their marriage, we will refrain from narrating it. It is enough to say that when finally Krsha escaped her monstrous husband, her body, spirit, and mind were battered to the point of utter brokenness. Her mind turned again and again to all the ways she had been hurt.

Exposed to the elements, and starving, she went mad and tossed away her lower garment. Her hands and feet were cracked, her coarse hair long and grey, her appearance grotesque. She wandered aimlessly until she came to Śrāvastī.

Now, the Buddha has stated that the ripening of sentient beings’ karma is inconceivable. And the fruits of Krsha’s past actions flowered such that she had the experience of coming to Jetavana…

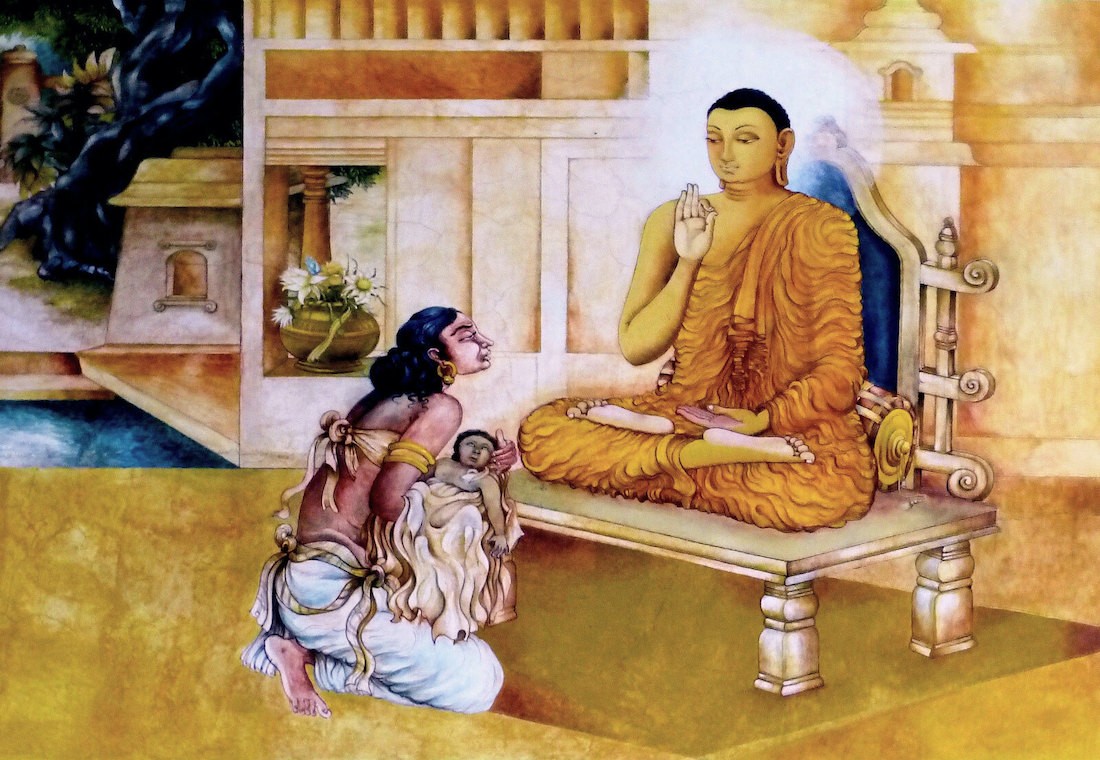

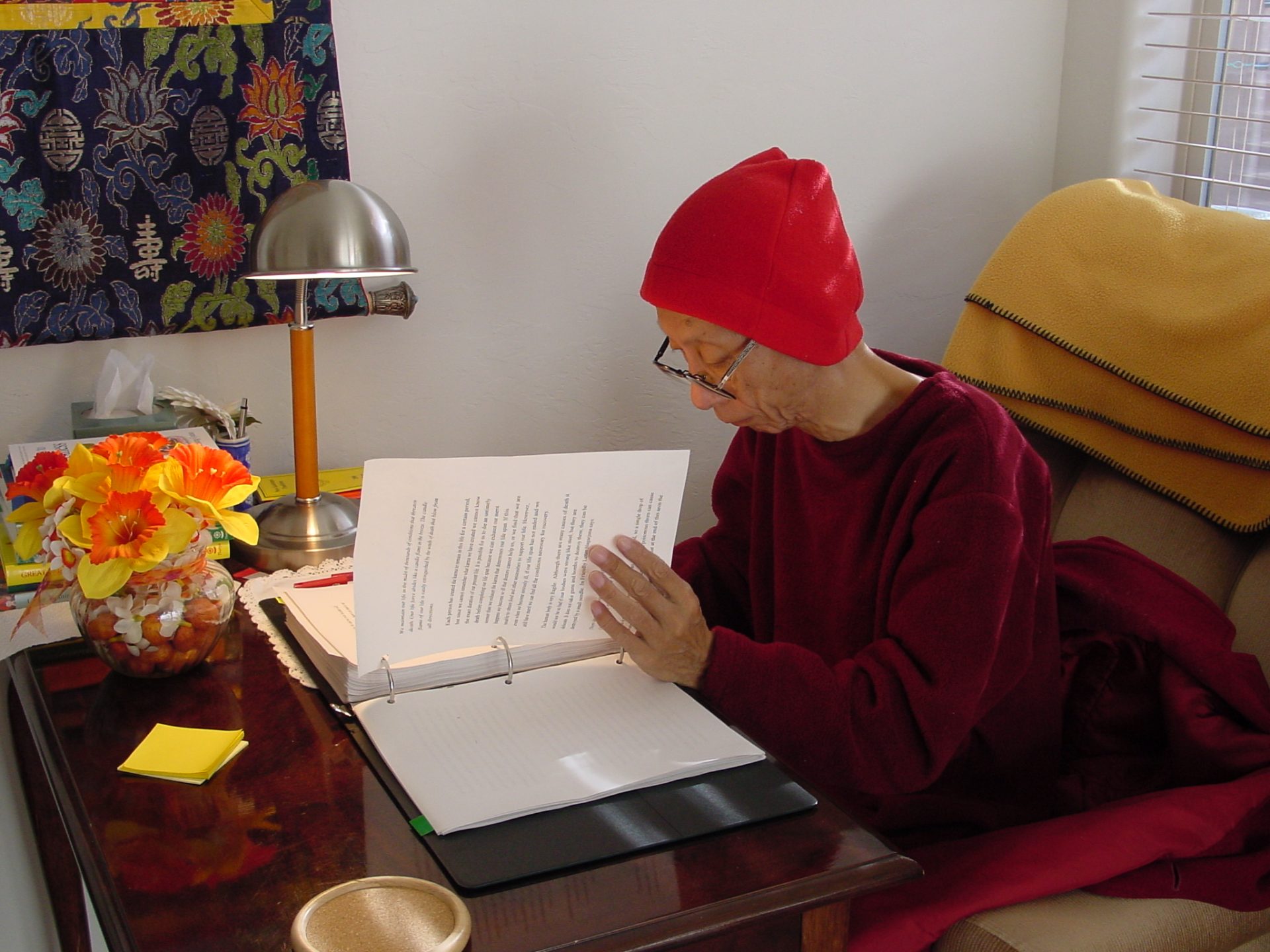

The Buddha sat in Jetavana Grove, teaching the dharma to a vast assembly of monks. To Krsha he appeared to shine, like a bright lamp placed in a golden vessel, if that vessel were hung high in a tree, and that tree were covered with gems. Just the sight of him was enough to return her to her senses. Realizing that she was unclothed amid the monastic assembly, she ran and huddled in a corner.

One can imagine the shock of the assembly of male monastics at her presence. As for the Buddha, his response was an expression of his infinite compassion. He turned to his assistant. “Ananda, give a cloak to the caravan leader’s wife Krsha Gautamī,” he said, referencing her happy first marriage, “and I shall give her a discourse on the dharma.”

Venerable Ananda brought her a cloak. Krsha Gautami wrapped it around herself, and went to where the Blessed One was seated, bowing before she took a seat at one side.

It would be hard for most of us to find the right words to say to Krsha Gautami at such a moment of extreme distress, but the Buddha understood her exactly. Although the story does not share the teaching he offered, it must have been perfectly suited to her heart. She immediately attained the realization of a stream enterer, buoyed up by a newfound understanding that would carry her inevitably, all the way to awakening.

Eyes wide, Krsha stood and requested ordination into the order of nuns. “Lord,” she said, “I wish to go forth from home life, to become a novice and achieve the state of full ordination in the monastic discipline and dharma which you have spoken so beautifully. Will the Blessed One permit me to practice the religious life in his presence?”

The Buddha assented, and handed her over to Mahaprajapati, the woman who had raised him and was now the head of the nun’s order. Mahaprajapati ordained her as a novice, then conferred upon her full ordination, trained her in the discipline, and gave her personal instruction. It was not long before Venerable Krsha attained arhatship, the state beyond all emotional distress. In time, the Buddha would commend her as foremost among the fully ordained nuns in upholding the monastic discipline.

***

Later, a group of younger nuns were questioning their decision to become ordained and curious about the pleasures of household life—whether it held something for them that they could not find as nuns. When they asked Venerable Krsha for advice, she offered them the story of all that had happened to her—the grief and pain that made up her former life.

As she recounted one by one the losses of her first husband, children, mother, and father, they grew disenchanted with their imaginings. As she turned to the violence of her second marriage, goosebumps covered their bodies, and they trembled as they listened.

It was then that Venerable Krsha, knowing what was in their hearts, gave them a discourse on the dharma such that they realized for themselves the four noble truths.

As her story is told in Pali, Kisa Gautami finds healing and renunciation as she goes door to door. Hearing the stories of others’ grief, she realizes the universality of suffering—no one suffers alone. This understanding begins to lift her despair.

As told in Sanskrit, the learning comes the other way round. As Venerable Krsha tells her story to the younger nuns, renunciation dawns within them. The two versions of the story agree: shared grief becomes the way to freedom.

♦

See here for the story of Mahaprajapati, the Buddha’s stepmother and the first nun.

Hollif

Hollif

![Mondly Review: Excellent In Most Areas, But… [2021]](https://www.dumblittleman.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/hhhhh-1.png)