A Brief Introduction to Mahayana Medicine

Exploring Buddhist healing through the lenses of wisdom, compassion, and ritual practice The post A Brief Introduction to Mahayana Medicine appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

“Come kneel in front of the statue,” the kindly old monk says to me as he grabs some implements from inside a small cabinet. I follow him over to the main altar, curious about what’s coming next. I’m visiting a small Vietnamese temple in downtown Philadelphia, on a mission to photograph Buddhist institutions across the city. Having just recovered from a severe cold, I ask him how someone in his community might deal with an illness using Buddhist principles and practices. Instead of explaining, he invites me to see for myself.

I kneel on the ground before the statue, a golden Quan Am, the most popular bodhisattva in Mahayana Buddhism (known across Asia as Guanyin, Kannon, Chenrezig, and Avalokiteshvara). The monk places a red cloth over my head, obscuring my vision, and begins to ring a bell over me. After some time, he sets the bell down and retrieves some blessed water from the altar. Wetting his fingers, he dabs, pats, and rubs my crown while whispering some mantras under his breath. In a few moments, the healing ritual is complete. My body has been blessed by the power of the bodhisattva, which will bring me mental and physical strength, resilience, health, and good luck.

This type of healing rite is a common occurrence across Asia. Although variations exist depending on culture and tradition, the basic logic of empowerment and blessing remains a standard response to illness across the Mahayana Buddhist world.

One of the key features of Mahayana Buddhism has been its extensive involvement with medical and healing activities. This continues to be a core commitment for Mahayana Buddhists worldwide. But what does healing have to do with the core mission of Buddhism?

Deconstructing Illness with Wisdom

Mahayana shares many philosophical similarities with early Buddhism. In particular, it agrees that the human condition is characterized by pervasive suffering or dissatisfaction that arises from our fundamental delusion about the nature of reality. Medical metaphors are common in all forms of Buddhism. In many sutra texts, the Buddha is frequently compared to a doctor, often referred to as the “Great Physician,” who diagnoses and treats humanity’s suffering with the medicine of the dharma.

The core of the Buddha’s diagnosis, the root cause of our suffering, is that we believe things are as they seem to be. As an antidote to this flawed way of thinking, Buddhism prescribes wisdom (Skt.: prajna; Pali: panna). Wisdom means correctly seeing that all phenomena lack any self or essential nature (anatman; anatta), and that everything is interdependent or dependently originated (pratityasamutpada; paticcasamuppada). Through philosophical contemplation and dedicated meditation on these ways of seeing, the Buddha promises that we can be cured of our deluded habits of mind. In particular, we can deconstruct the pernicious belief in permanent or separate selves, and finally see things “as they really are.”

Mahayana accepts all of these viewpoints and builds on them. Since there is no inherent essence or substantiality, Mahayana teachings emphasize that phenomena can exist only in relation to other phenomena. One illustration of this interconnection is the metaphor of Indra’s Net from the popular Avatamsaka Sutra. Imagine the entire universe being a bejeweled net, where each gem reflects all the others. Similarly, each object across the universe simultaneously reflects all the other objects. The modern Buddhist leader Thich Nhat Hanh famously referred to this kind of interconnectedness as “interbeing.” He pointed out how an object like paper is inseparable from trees, rain, the sun, the logger who cut the trees, the food he ate, and so on and so forth, eventually implicating the entire universe. To use typical Mahayana parlance, we could say that paper—and by extension, illnesses and every other seemingly distinct concept—is characterized by emptiness (sunyata), or the absence of any independent existence as a separate entity.

Like early Buddhism, Mahayana has always valued both philosophically grasping and experientially realizing emptiness as the path to awakening or enlightenment. However, this wisdom also has a more practical application when it comes to illness. One text that is particularly clear in this regard is the Vimalakirti Sutra. In Chapter 5, the hero of the story, the fully enlightened layman named Vimalakirti, provides a teaching on the emptiness of the body and of illness. The body, he says, is simply a name given to a conglomeration of the material elements; it is like a mirage, a phantasm, a dream. Likewise, illness is merely a false concept, a confused view that arises from attachment to the self and objectification of phenomena. Later commentators have suggested that truly understanding emptiness not only allows one to experience equanimity toward the suffering of illness but also might even eliminate the symptoms.

Healing the World with Skillful Means

Although wisdom has always remained a priority for adherents of the Mahayana, a new idea developed in this tradition has provided a second focal point for practice. While not detracting from the importance of developing wise ways of seeing, Mahayana thinkers equally emphasized what they called “skillful means,” or “expedient means” (upaya). Foundational Mahayana texts, such as the Lotus Sutra and the Prajnaparamita sutras, introduced the idea that it is essential to always balance wisdom and skillful means. Later writers likened this balance to the two wings of a bird, which must be the same size and strength for it to fly. For the Mahayana, focusing solely on wisdom came to be seen as an “inferior vehicle” unbefitting of a true Buddhist.

But how does one skillfully engage with this world? Given the interconnectedness of all things, the only sensible answer is to act in a way that maximizes the benefits for all sentient beings everywhere. Yes, the ultimate truth is that none of these beings exist as separate selves, but simply using that as an excuse not to care is anathema to Mahayana Buddhists. From the vantage point of skillful means, the central concern is discovering whatever may be of highest practical benefit—the most loving, healing, or compassionate response in any given circumstance. That is to say, the ethics of skillful means are defined not in the ontological terms of what is real but rather in the pragmatic terms of what is most helpful.

The ethics of skillful means are defined not in the ontological terms of what is real but rather in the pragmatic terms of what is most helpful.

In fleshing out the notion of skillful means, Mahayana built upon early Buddhist precedents rather than inventing new traditions from scratch. Already, pre-Mahayana Buddhist tradition had been teaching practitioners to generate positive mental states in various ways. Meditations or contemplations cultivating the four “sublime abidings” (brahmaviharas)—kindness, compassion, sympathetic joy, and equanimity—had existed even before Buddhism and had been incorporated into early Buddhist practice. Since they do not focus on the deconstruction of reality that is necessary for wisdom, these practices were not thought to lead to full liberation on their own. Nevertheless, they were cherished as transformative practices that could positively affect one’s daily life as well as future rebirths. Practices such as these took center stage in Mahayana. A host of meditations, visualizations, chanting regimens, rituals, and other techniques were developed to immerse the practitioner in a field of beneficial thoughts and positive mental states.

Since earlier Buddhist tradition prioritized wisdom above all else, it tended to hold the viewpoint that transcendental practices leading to liberation were more important than worldly activities. The latter were often held to be distractions from the essential vocation of the monastic. In early Buddhism, the status of healing activities was sometimes ambiguous. While in some early texts, the Buddha exhorts monastics to nurse one another when sick, in others, he calls healing the laity a “wrongful livelihood” and prohibits his community of followers from engaging in it.

With the Mahayana emphasis on skillful means, however, these priorities were reshuffled. Along with Mahayana’s integration of wisdom and skillful means came the conviction that any action helping others further along their path to liberation was as valuable as pursuing one’s enlightenment—if not more so. Indeed, cultivating the intent to act in ways that contribute to the liberation of all beings (bodhicitta) became the centrally defining characteristic of Mahayana practice.

Mahayana Medicine Today

With the desire to compassionately help others at its core, Mahayana came to encourage a wholehearted engagement with medical and healing activities. Across the Mahayana world, monastic centers served as important locations for medical learning. Hospitals and hospice facilities were integral parts of any large monastery’s layout and frequently were open to the public. Trained monastic physicians, nurses, and caretakers staffed such facilities, and their education became a matter of institutional priority. In Buddhist cultures from China to Japan, Tibet, and Southeast Asia, these medically oriented centers were supported by rulers and governments and were often integrated into the state administrative structures.

To this day, major monastic and lay health care institutions continue to be active. Some prominent examples include the Men-Tsee-Khang in Dharamasala; the Tzu Chi Foundation, based in Taiwan; and the Won Buddhist order, based in Korea. While some outside the tradition might consider worldly healing activities to be superfluous or even a distraction from the goal of awakening, Mahayana Buddhists view supporting, volunteering for, and promoting such initiatives as a central part of their spiritual mission.

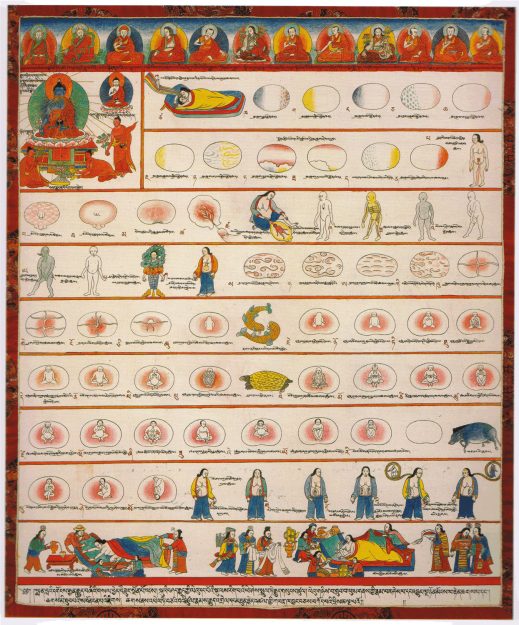

Illustration (Conception to Birth) from Ornament to the Mind of Medicine Buddha: Blue Beryl Lamp Illuminating Four Tantras written around the year 1720 by Desi Sangye Gyatso (1653–1705), the regent (Desi) of the 5th Dalai Lama. | Image via Wikimedia Commons

Illustration (Conception to Birth) from Ornament to the Mind of Medicine Buddha: Blue Beryl Lamp Illuminating Four Tantras written around the year 1720 by Desi Sangye Gyatso (1653–1705), the regent (Desi) of the 5th Dalai Lama. | Image via Wikimedia CommonsIn addition to supporting medical institutions, Mahayana practitioners also continue to use a wide range of interventions to alleviate the suffering caused by illness. The tradition contains a vast toolkit of prayers, chanting, purification rites, offerings, and karmic cleansing procedures that have been retooled to focus on healing. Across Asia, the specifics of these practices have varied. But there have also been some common themes. Generally speaking, the logic behind a healing ceremony such as the one I participated in in Philadelphia is to ritually tap into the beneficial powers or associations of various Buddhas or celestial bodhisattvas. Devotees are taught to visualize auspicious imagery associated with these figures. They train to sonically attune to specific mantras, dharanis, or the names of deities. They learn over time to saturate their minds with positive feelings, sensations, or resonances as a resource against ailments of all kinds.

Different traditions have additionally incorporated forms of energy work to heal oneself or others. Such practices are commonly understood through frameworks of qi in East Asia or “winds” (Skt.: prana; Tib.: rlung; etc.) elsewhere in Asia. In many places, energy is also conceived of in the form of light. In these practices, adepts learn to produce, enhance, circulate, and store energy in different parts of the body. Energy can be directed toward an illness, can be projected externally to heal others, or can be used for general strength to protect against sickness. Because they draw on many of the same ideas and precedents, these concepts share similarities with other Asian medical and body cultivation systems such as acupuncture, yoga, qigong, and reiki, among others.

Mahayana healing practices are diverse and culturally specific, making it difficult to generalize about them. However, these kinds of engagements are vitally important in the lived experience of Buddhists all over Asia and beyond when facing acute medical conditions, chronic illnesses, mental health crises, and other similar situations. When seeking holistic healing that integrates body and mind and is compatible with spirituality, Western Buddhists also may benefit from experimenting with these kinds of healing practices.

Healing with Loving Light

These two healing practices are based on a visualization that can be found anywhere across the Mahayana world. I met monks in Japan who used this kind of practice to extend compassionate healing energies worldwide during the Covid pandemic, and I once met a surgeon in South Korea who routinely practices this for his patients whenever he operates on them.

Healing Practice for Yourself

Sit comfortably, close your eyes, and take a few breaths to relax your body. When you are present and calm, begin to imagine a source of unalloyed love and healing situated above your head. Traditionally, this would be a Mahayana figure, such as a buddha or bodhisattva—Guanyin, Tara, and the Medicine Buddha are particularly popular, as are certain symbols associated with them. However, what’s most important is to use an image that resonates with you. Bring this figure into focus, spending time visualizing the details of their face, body, clothing, and other attributes.

When the image has gained a certain amount of clarity and stability in your mind’s eye, then visualize this figure emanating a healing, loving energy down into the crown of your head. It may be helpful to picture this as an aura of glowing light or maybe even as sunrays. Have the light fill you up, illuminating and healing every corner of your body and mind. You can rest in this image in a general way, or continue to focus on the details or on specific parts of your body, whichever enables the experience to deepen and enrich itself.

The more you practice healing yourself with this loving divine light, the more rapidly you will be able to bring it to mind. Over time, you will also develop the capacity to feel sensations related to healing in your body: perhaps a warmth, a release of tension, or even a deep tranquility. Bathe yourself in this reservoir of positive images, sensations, and feelings whenever you need to recharge, soothe, or heal yourself.

Healing Practice for Others

After you have developed the capacity to saturate your mind and body in the loving and healing light through the steps above, you can begin to practice extending those feelings outward toward other people. While you will still visualize the source of light coming from above your head, now you can also become a transmitter of that energy to others. Start as before, but when your own body is filled with loving light, imagine that it begins to glow from your pores. Visualize an aura or discrete rays of sun emitting into the space around you, and extending out to illuminate the world.

Practice directing this compassionate healing energy toward individuals who are in need, or just share it with anyone you encounter throughout your day. If someone you know falls sick or has a chronic condition, you can specifically direct this healing light toward them. Imagine the light illuminating their body, clearing out their ailments and pain, leaving their body as radiant as your own.

Whether working with yourself or others, when your healing session comes to an end, you finish by wishing for all beings everywhere across the universe to be happy and well. Then give thanks to the source of light, whoever or whatever that may be for you. Try to carry the resonances of love and healing with you as you go about the rest of your day.

Koichiko

Koichiko