A Theravadan monk explains how Buddhist mindfulness and clinical therapeutic mindfulness are complimentary — but not the same

By Sanathavihari Bhikkhu (Bio at bottom of feature.) As a Buddhist monk, I have some misgivings about the way in which mindfulness is understood and used today. My biggest concern is the misunderstanding of mindfulness, which can often lead...

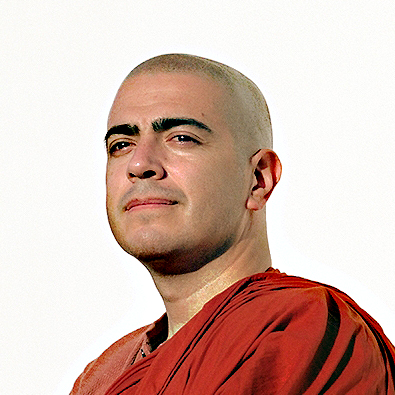

By Sanathavihari Bhikkhu

(Bio at bottom of feature.)

Sanathavihari Bhikkhu

Sanathavihari BhikkhuAs a Buddhist monk, I have some misgivings about the way in which mindfulness is understood and used today. My biggest concern is the misunderstanding of mindfulness, which can often lead to the abuse of it. Allow me to begin with a teaching of the Buddha from the Anguttara Nikaya:

“O monks, there are two kinds of sickness: one physical and one mental. It is possible that a person can stay one day, two days, one year, ten years, fifty years or more, without having any physical disease; but, it is rare to find someone who does not suffer from mental illness, even for a brief moment; except those who have already awakened.”

Buddhist monk meditating.

Buddhist monk meditating.

In another well-known Buddhist phrase, it states “sabbeputtanjhana umattaka” (sah-bay-poo-tan-jah-nah) (oom-ah-tah-kah) – “all beings are insane or mad.” To be sure, this statement may seem rather drastic, but in the context of the Buddha’s teaching, this phrase speaks to the insanity of the useless activities that everyone does. However, the Buddha was quick to teach that this “insane-like-state-of-mind” need not be permanent:

“The mind, in its natural state, is pure, but it is only polluted (contaminated) by external factors.”

—Pabhassara Sutta

This is our ray of hope! The contaminated mind (e.g., useless thoughts, beliefs, opinions, and activities) is not permanent – it can be purified, back to a natural state.

From Sanathavihari Bhikkhu’s Youtube channel (20 minutes of breathing meditation). To visit the channel page>>

Understanding Mindfulness

There is a lot of information on mindfulness. A quick Google search reveals endless websites, articles, books, Podcasts, YouTube channels, etc. on the topic. Yet these sources rarely consider the Buddha’s original teachings on mindfulness. Generally speaking, modern society’s understanding of ‘mindfulness’ is based on a mundane (common) meaning. This misunderstanding of the true meaning of mindfulness inadvertently imposes limitations on the effectiveness and potential of mindfulness. What’s more, without any knowledge on the origin of the concept, more limitations emerge, thus restricting and repurposing the whole meaning of mindfulness.

In order to get any real benefit from mindfulness meditation practice, we need a clear understanding of what mindfulness actually is. From the standpoint of the creator of the concept, the Buddha, the mundane meaning of mindfulness is like a car or a bicycle without wheels. In other words, with the common meaning of the word, the foundation of what makes mindfulness work is missing altogether. You can certainly sit inside of a nice vehicle, but you can’t actually go anywhere without wheels. The same is true when one practices mindfulness without any understanding of the purpose or the method.

Proper Application of Mindfulness

Despite the encouraging results of current mindfulness studies, the mere integration of mindfulness practice does not guarantee positive results for every single person. For instances, those who suffer from afflictions such as generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), major depressive disorder (MDD) or bipolar disorders (I & II), frequently require specialized assistance from qualified providers. This means that a monk alone, even one very experienced in mindfulness practice, may not be a viable source when the need for professional help is present. In an article published in 2017 in the Journal for the Association for Psychological Science [1], researchers stated the following:

“During the past two decades, mindfulness meditation has gone from being a fringe topic of scientific investigation to being an occasional replacement for psychotherapy, tool of corporate well-being, widely implemented educational practice, and ‘key to building more resilient soldiers.’ Yet the mindfulness movement and empirical evidence supporting it have not gone without criticism. Misinformation and poor methodology associated with past studies of mindfulness may lead public consumers to be harmed, misled, and disappointed. Addressing such concerns, the present article discusses the difficulties of defining mindfulness, delineates the proper scope of research into mindfulness practices, and explicates crucial methodological issues for interpreting results from investigations of mindfulness.”

Many different types of interventions or methods of therapy are integrating mindfulness; developing different ways of applying mindfulness, as well as providing distinct definitions for the methods. As taught by the Buddha, the definition of mindfulness, the method of practice, and the purpose of it, is singular. Understanding mindfulness, according to the Buddha’s teaching, would resolve any issues with regard to the determination of what mindfulness is.

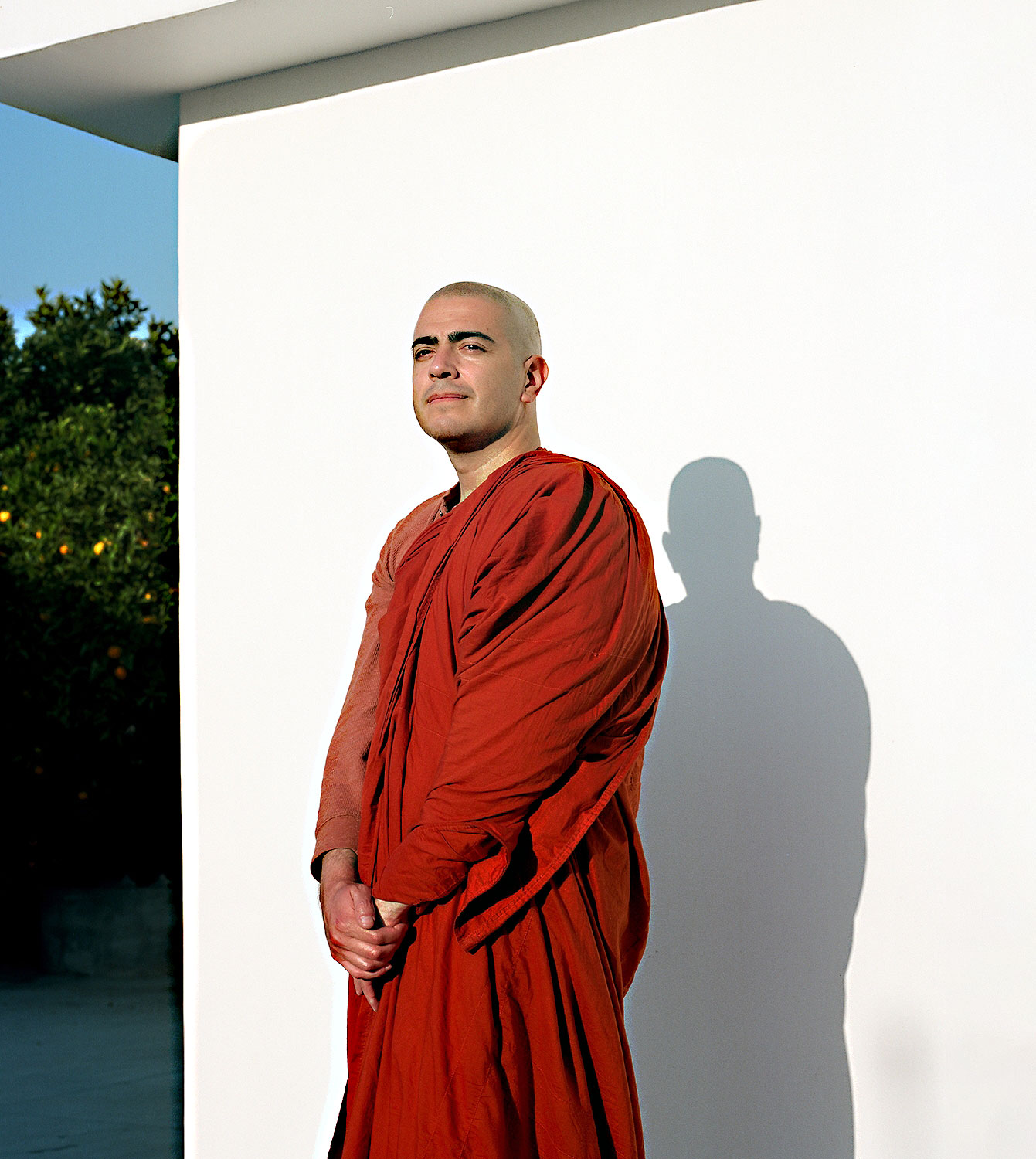

Sanathavihari Bhikkhu.

Sanathavihari Bhikkhu.

Buddhist Mindfulness Goal and Psychotherapeutic Goals

What is the goal of mindfulness meditation from a Buddhist practitioner’s perspective? The goal is to train the mind by focusing on the four foundations of mindfulness (cattaro satipaṭṭhānā), e.g., the breath for better focus, clearer thinking, and ultimately the cessation of all mental afflictions i.e., Nirvana. Science has even discovered that subtle physiological changes take place during meditation practices, such as a decrease in heartrate, lower blood pressure, and lowered brain activity (in some regions). In other words, the cultivation of various wholesome mental factors such as samatha, vipassana, or mindfulness, with the goal of “internally steadying” or stabilizing the “unstable mind”, resulting in a state of quiescence and tranquility.

But a Buddhist practitioner seeks to go beyond mere tranquility – the practitioner aims to understand the nature of mind (the organism in the environment) in direct connection with the things that condition suffering. The goal of secular/clinical science, and in particular psychopathology the physiological results stemming from mindfulness. This approach often utilizes only one aspect of the practice in order to achieve the targeted goal, i.e., symptom reduction by way of the physiological responses produced by mindfulness meditation.

Mindfulness meditation is contemplative, meaning that it is a practice that employs or invokes focused attention. The practitioner becomes deeply emersed in observing the aspects of one’s own mental and physical experience. In other words, the practitioner becomes familiar with one’s own totality of experience. Some psychological sciences have drawn from the Buddha’s teachings, but isolate only particular aspects of the practice. Therefore, the goal of mindfulness meditation from a scientific standpoint should not be confused with the goal of mindfulness meditation from a Buddhist practitioner.

Therapeutic mindfulness methods and goals are not necessarily the same as Buddhist mindfulness.

Therapeutic mindfulness methods and goals are not necessarily the same as Buddhist mindfulness.

An example that highlights these differences comes from a 2015 study [2] wherein the effects of mindfulness meditation were compared to the use of various antidepressants. The study concluded that mindfulness meditation produced similar attention-related benefits to that of medication alone. When the effects of mindfulness meditation were compared to the psychological methodology known as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), the results of applying CBT outperformed mindfulness meditation. This is where the confusion between science and Buddhism occurs: although CBT ‘outperformed’ mindfulness meditation, the results sought by science stop short of the results sought by a Buddhist practitioner. To wit, the results from a scientific standpoint are inconclusive from the Buddhist perspective.

Buddhist monk meditating under a tree mindfully.

Buddhist monk meditating under a tree mindfully.

Further, in a 2019 meta-analysis [3] centered on the effects of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) for the treatment of current depressive symptoms, moderate effect sizes were found. This finding suggests that MBCT may be of comparable efficacy to other therapies that are ordinarily offered for current depressive symptoms at post-treatment.

As a result of the adoption of certain elements of Buddhist mindfulness meditation, science has created a methodology for the treatment of various mental health issues. This methodology is known as Mindfulness Based Therapy or MBT. Labels such as this cause confusion about mindfulness meditation, creating the concept that Buddhist mindfulness meditation is the same as the scientific concept. For example, a study conducted in 2010 [4] concluded that MBT was effective for improving symptoms of anxiety and depression. Within the results of this study are the real clues to understanding the difference between mindfulness meditation from a Buddhist perspective and science. While science seeks to merely alleviate the symptoms, the Buddhist practitioner seeks to eradicate the root cause of the symptoms. The efficacy of mindfulness meditation that has been integrated into the various methodologies developed by clinical psychology is severely limited to treating symptoms. Conversely, the efficacy of Buddhist mindfulness meditation focuses on removing the cause/root that creates the symptoms in the first place. But, the general public, and even many lay Buddhist practitioners, simply do not understand this.

Where it all began

To understand what mindfulness meditation is, one must first understand where this phrase originated. Most web sources define Buddhist breath meditation as Anapanasati (ah-nah-pah-nah-sah-tee), but this is really an oversimplification. The “mindfulness” part of mindfulness meditation comes from the Pali word sati (sah-tee). However, many of the words use by the Buddha have multiple meanings depending on the context in which he used them. Sati is one of those words. It can either mean “attention” or it can mean “mindfulness.” However, in relation to the practice of meditation, the word sati has a much deeper meaning and refers to one’s “mindset,” rather than just the common concept of being mindful, attentive, or focused.

In order to properly engage in mindfulness meditation, in true Ānapānasati/Satipaṭṭhāna, one must have a particular “mindset.” This means that in addition to merely paying attention to the breath, one intentionally focuses on the moral and immoral implications of one’s thoughts, speech and actions. This means that one intentionally gives rise to a way of thinking that is aimed at gradually removing greed (lobha), anger (dosa) and ignorance (moha) from one’s mind. A common misconception is the idea that one must remove “all thoughts” during mindfulness meditation. However, the key to correct sati is to be aware of negative, unbeneficial thoughts that stain our speech and actions, and stop them as they arise. Indeed, the entire point of mindfulness meditation is to replace bad thoughts with good thoughts, i.e., direct one’s attention towards “good things”, and move away (asati) from “bad things.” This is what is called keeping the sati mindset.

When engaging in mindfulness meditation, the goal is two-fold: the removal of bad thoughts that arise (samvara, pahāna) and the cultivation of good thoughts (bhāvanā, anurakkhana). In the Buddha’s teachings these two mental activities are called akusala and kusala, respectively. Akusala, or bad moral thoughts and deeds, causes stress and suffering. Kusala, or good moral thoughts and actions, leads to a calm mind at a fundamental level. Consistent akusala thoughts and deeds, particularly those that are highly immoral, produce consequences that can result in an unfavorable rebirth.

Monks meditating.

Monks meditating.

The word anapanasati, from which the concept of breath meditation originates, is a construct of several Pali words. The first is “ana,” and the second is “apana,” which means taking in and putting out. Combining these two words with sati, has a meaning of air entering-going out-mindfulness (attention). The deeper contextual meaning is that a practitioner maintains their thinking mind (mindset) on good moral dhamma, known as kusala dhamma, while at the same time intentionally identifying and getting rid of bad moral dhamma, known as akusala dhamma.

Buddhist Temples and Meditation Centers are not a replacement for Professional Mental Health services

As a Buddhist monk, I take interest in people’s suffering. I become concerned when I see that the actions and beliefs of people restrict their understanding of spiritual concepts, such as mindfulness. I recognize that many people believe that if they simply go to the temple, they will somehow be free from mental problems. Benefits of correct mindfulness practices are many, but the use of alternative methods, such as decontextualized mindfulness, for achieving mental well-being are limited, from a Buddhist perspective.

Benefits may happen, but Buddhist temples are not mental health clinics, nor are they meant to be. Sure, there is documented evidence showing that being part of a religious group and attending religious places can help with people’s overall well-being by providing a sense of purpose and meaning. It has even been shown to help people that are experiencing physical illnesses, such as cancer[5]. But mental well-being is not the entire purpose of a temple. Monks and temples are not suitable replacements for clinics centered on the treatment of mental health issues.

When dealing with mental health issues, there really is not much room for haphazard treatments and using Buddhist concepts as an alternative to professional help is the incorrect use of the Buddha’s teachings. To be sure, I have both seen in others and experienced personally the beneficial effects that meditation has on mental and physical health. I do, however, also recognize that these benefits do not always have the same effects for those with mental disorders and can at times even be detrimental.

Ethics and Responsibilities

People can become very excited and encouraged by the Buddha’s teachings, and this is a good thing. However, selecting only certain teachings, such as mindfulness, cherry-picked based solely on your point of view, is not the way to practice, mindfulness meditation or otherwise. While it may be true that modern science has positive things to say about mindfulness, without a clear understanding of what mindfulness actually is, and its purpose, the approach is incorrect. Approaching mindfulness practice absent of these factors, the true benefits are lost.

It is clear that the Buddhist concept of mindfulness differs greatly from the concepts of mindfulness developed by the psychological sciences. This brings us back to the phrase “sabbeputtanjhana umattaka” (sah-bay-poo-tan-jah-nah) (oom-ah-tah-kah), mentioned at the beginning of this paper. While modern psychological sciences have derived benefits for mental health patients through the application of certain elements of Buddhist mindfulness, they are unable to discover the end to all dukkha (suffering/ unsatisfactoriness).

As a Buddhist monk, I teach the Buddha’s concepts of mindfulness to lay practitioners. But, at times people come to temple expecting to be cured of mental disorders through mindfulness meditation. While Buddhist mindfulness meditation can be effective up to a certain degree for these individuals, sometimes the level of mental afflictions that a person presents with is such that it requires the aid of professional mental health interventions.

As Buddhists, we have a deep degree of responsibility to teach ethically and direct people to methods that are the most beneficial. Therefore, the manner in which we promote mindfulness meditation must be done with honesty and integrity. As monks and Buddhist practitioners, we must be transparent and direct when teaching and promoting these practices. Equality important, however, is the necessity to be compassionate toward those with mental afflictions.

The Buddha teaches us to be a “kalyana mitta” (kahl-lee-ah-nah) (mee-tah), i.e., someone who helps others make progress. Part of being a kalyana mitta means recognizing, with compassion, that some persons may require medical intervention in addition to mindfulness meditation. Knowing and understanding the correct concept of mindfulness meditation will help us to help others and be a true kalyana mitta.

Notes

[1] Van Dam NT, van Vugt MK, Vago DR, et al. Mind the Hype: A Critical Evaluation and Prescriptive Agenda for Research on Mindfulness and Meditation. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2018;13(1):36-61. doi:10.1177/1745691617709589.

[2] Kuyken W, Hayes R, Barrett B, Byng R, Dalgleish T, Kessler D, Lewis G, Watkins E, Brejcha C, Cardy J, Causley, A., Cowderoy, S., Evans, A., Gradinger, F., Kaur, S., Lanham, P., Morant, N., Richards, J., Shah, P., & Sutton, H. (2015). Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy compared with maintenance antidepressant treatment in the prevention of depressive relapse or recurrence (PREVENT): a randomized controlled trial. Lancet, 386 North American Edition (9988), 63–73. https://doi-org.msmc.idm.oclc.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62222-4

[3] Goldberg, S. B., Tucker, R. P., Greene, P. A., Davidson, R. J., Kearney, D. J., & Simpson, T. L. (2019). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for the treatment of current depressive symptoms: a meta-analysis. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 48(6), 445–462. https://doi-org.msmc.idm.oclc.org/10.1080/16506073.2018.1556330

[4] Hofmann, SG, Sawyer, AT, Witt, AA, & Oh, D. (2010). The Effect of Mindfulness-Based Therapy on Anxiety and Depression: A Meta-Analytic Review. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 78 (2), 169–183. https://doi-org.msmc.idm.oclc.org/10.1037/a0018555

[5] Religion, Spirituality, and Physical Health in Cancer Patients: A Meta-Analysis, Heather S. L. Jim PhD,James E. Pustejovsky PhD,Crystal L. Park PhD,Suzanne C. Danhauer PhD,Allen C. Sherman PhD,George Fitchett PhD,Thomas V. Merluzzi PhD,Alexis R. Munoz MPH,Login George MA,Mallory A. Snyder MPH,John M. Salsman PhD. Volume121, Issue21 10 August 2015 https://doi-org.msmc.idm.oclc.org/10.1002/cncr.29353

Tfoso

Tfoso