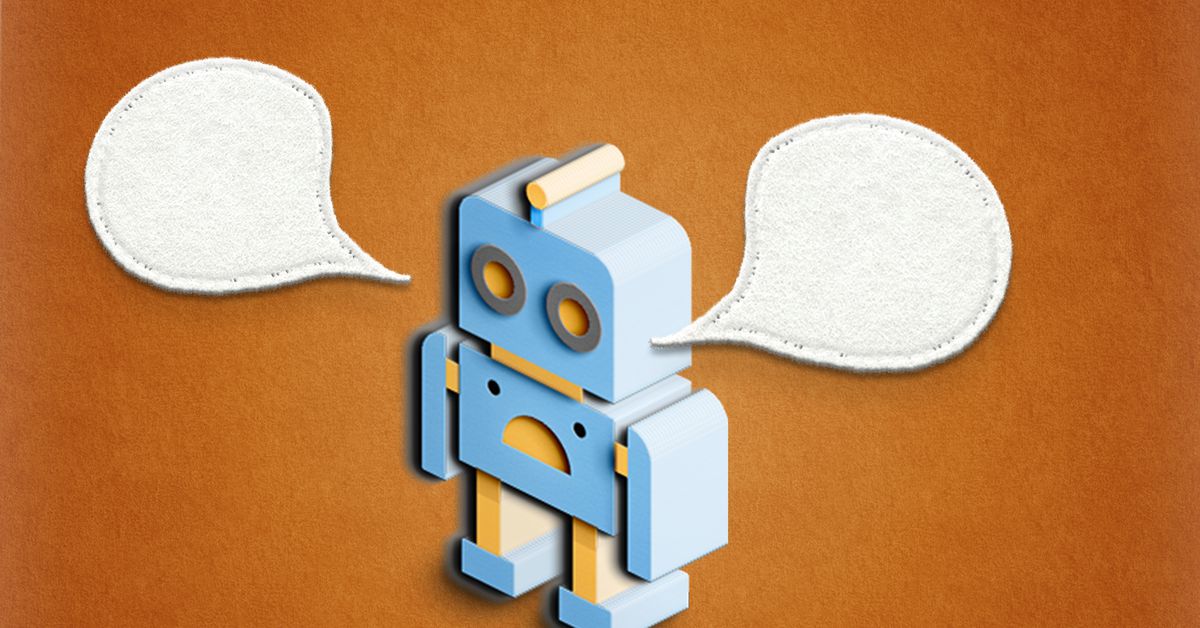

AI is finally good at stuff, and that’s a problem

ChatGPT is another sign that AI is getting a lot better. | Carol YepesHere’s why you’ve been hearing so much about ChatGPT. A few weeks ago, Wharton professor Ethan Mollick told his MBA students to play around with GPT,...

A few weeks ago, Wharton professor Ethan Mollick told his MBA students to play around with GPT, an artificial intelligence model, and see if the technology could write an essay based on one of the topics discussed in his course. The assignment was, admittedly, mostly a gimmick meant to illustrate the power of the technology. Still, the algorithmically generated essays — although not perfect and a tad over-reliant on the passive voice — were at least reasonable, Mollick recalled. They also passed another critical test: a screening by Turnitin, a popular anti-plagiarism software. AI, it seems, had suddenly gotten pretty good.

It certainly feels that way right now. Over the past week or so, screenshots of conversations with ChatGPT, the newest iteration of the AI model developed by the research firm OpenAI, have gone viral on social media. People have directed the tool, which is freely available online, to make jokes, write TV episodes, compose music, and even debug computer code — all things I got the AI to do, too. More than a million people have now played around with the AI, and even though it doesn’t always tell the truth or make sense, it’s still a pretty good writer and an even more confident bullshitter. Along with the recent updates to DALL-E, OpenAI’s art-generation software, and Lensa AI, a controversial platform that can produce digital portraits with the help of machine learning, GPT is a stark wakeup call that artificial intelligence is starting to rival human ability, at least for some things.

“I think that things have changed very dramatically,” Mollick told Recode. “And I think it’s just a matter of time for people to notice.”

If you’re not convinced, you can try it yourself here. The system works like any online chatbot, and you can simply type out and submit any question or prompt you want the AI to address.

How does GPT even work? At its core, the technology is based on a type of artificial intelligence called a language model, a prediction system that essentially guesses what it should write, based on previous texts it has processed. GPT was built by training its AI with an extraordinarily large amount of data, much of which comes from the vast supply of data on the internet, along with billions of dollars, including initial funding from several prominent tech billionaires, including Reid Hoffman and Peter Thiel. ChatGPT was also trained on examples of back-and-forth human conversation, which helps it make its dialogue sound a lot more human, as a blog post published by OpenAI explains.

OpenAI is trying to commercialize its technology, but this current release is supposed to allow the public to test it. The company made headlines two years ago when it released GPT-3, an iteration of the tech that could produce poems, role-play, and answer some questions. This newest version of the technology is GPT-3.5, and ChatGPT, its corresponding chatbot, is even better at text generation than its predecessor. It’s also pretty good at following instructions, like, “Write a Frog and Toad short story where Frog invests in mortgage-backed securities.” (The story ends with Toad following Frog’s advice and investing in mortgage-backed securities, concluding that “sometimes taking a little risk can pay off in the end”).

The technology certainly has its flaws. While the system is theoretically designed not to cross some moral red lines — it’s adamant that Hitler was bad — it’s not difficult to trick the AI into sharing advice on how to engage in all sorts of evil and nefarious activities, particularly if you tell the chatbot that it’s writing fiction. The system, like other AI models, can also say biased and offensive things. As my colleague Sigal Samuel has explained, an earlier version of GPT generated extremely Islamophobic content, and also produced some pretty concerning talking points about the treatment of Uyghur Muslims in China.

Both GPT’s impressive capabilities and its limitations reflect the fact that the technology operates like a version of Google’s smart compose writing suggestions, generating ideas based on what it has read and processed before. For this reason, the AI can sound extremely confident while not displaying a particularly deep understanding of the subject it’s writing about. This is also why it’s easier for GPT to write about commonly discussed topics, like a Shakespeare play or the importance of mitochondria.

“It wants to produce texts that it deemed to be likely, given everything that it has seen before,” explains Vincent Conitzer, a computer science professor at Carnegie Mellon. “Maybe it sounds a little bit generic at times, but it writes very clearly. It will probably rehash points that have often been made on that particular topic because it has, in effect, learned what kinds of things people say.”

So for now, we’re not dealing with an all-knowing bot. Answers provided by the AI were recently banned from the coding feedback platform StackOverflow because they were very likely to be incorrect. The chatbot is also easily tripped up by riddles (though its attempts to answer are extremely funny). Overall, the system is perfectly comfortable making stuff up, which obviously makes no sense upon human scrutiny. These limitations might be comforting to people worried that the AI could take their jobs, or eventually pose a safety threat to humans.

But AI is getting better and better, and even this current version of GPT can already do extremely well at certain tasks. Consider Mollick’s assignment. While the system certainly wasn’t good enough to earn an A, it still did pretty well. One Twitter user said that, on a mock SAT exam, ChatGPT scored around the 52 percentile of test takers. Kris Jordan, a computer science professor at UNC, told Recode that when he assigned GPT his final exam, the chatbot received a perfect grade, far better than the median score for the humans taking his course. And yes, even before ChatGPT went live, students were using all sorts of artificial intelligence, including earlier versions of GPT, to complete their assignments. And they’re probably not getting flagged for cheating. (Turnitin, the anti-plagiarism software maker, did not respond to multiple requests for comment).

Right now, it’s not clear how many enterprising students might start using GPT, or if teachers and professors will figure out a way to catch them. Still, these forms of AI are already forcing us to wrestle with what kinds of things we want humans to continue to do, and what we’d prefer to have technology figure out instead.

“My eighth grade math teacher told me not to rely on a calculator since I won’t have one in my pocket all the time when I grow up,” Phillip Dawson, an expert who studies exam cheating at Deakin University, told Recode. “We all know how that turned out.

This story was first published in the Recode newsletter. Sign up here so you don’t miss the next one!

In our recent reader survey, we were delighted to hear that people value Vox because we help them educate themselves and their families, spark their curiosity, explain the moment, and make our work approachable.

Reader gifts support this mission by helping to keep our work free — whether we’re adding nuanced context to events in the news or explaining how our economy got where it is. While we’re committed to keeping Vox free, our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism does take a lot of resources, and gifts help us rely less on advertising. We’re aiming to raise 3,000 new gifts by December 31 to help keep this valuable work free. Will you help us reach our goal and support our mission by making a gift today?

Troov

Troov