‘Aubade’

Yuki Tanaka’s poems drift between voices and consciousnesses in depicting the shifting nature of the self. The post ‘Aubade’ appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

Yuki Tanaka’s poems drift between voices and consciousnesses in depicting the shifting nature of the self.

By Yuki Tanaka Feb 08, 2026

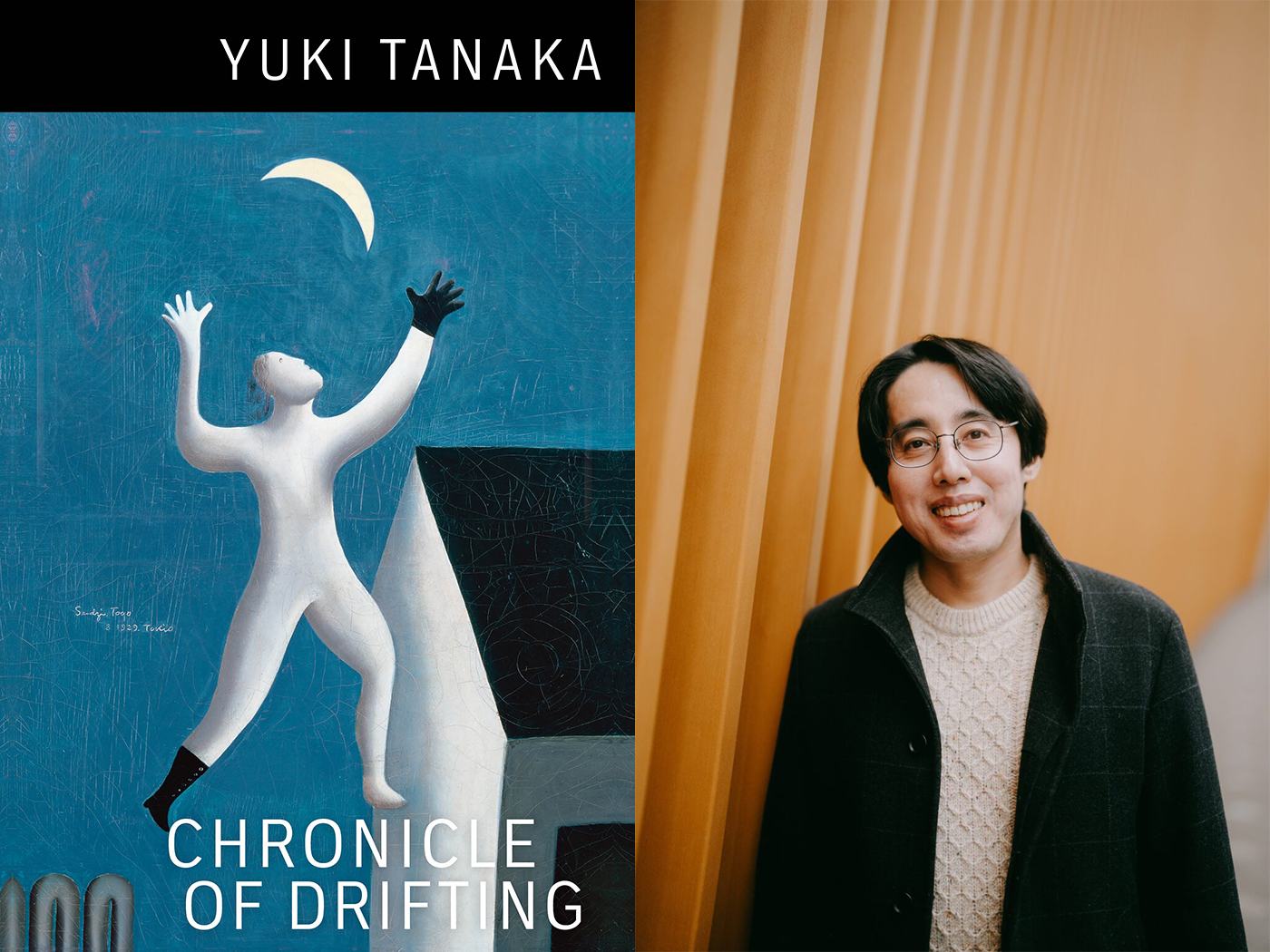

Yuki Tanaka’s debut full-length poetry collection, Chronicle of Drifting, explores the fluidity of the self and the shifting nature of identity and imagination. Taking inspiration from the Japanese traditions of tanka and haiku, as well as folk tales of tricksters and transformations, Tanaka crafts a dreamlike world where the boundaries between self and other—and the living and the dead—warp and dissolve. Many of the poems adhere to an eerie dream logic, flitting between voices and consciousnesses as shifting figures drift through “a world / filled with the dying.” Speakers listen to the moon and ask the sky to keep them company; a Tokyo flaneur, when not in motion, liquefies into a “stagnant pool of water reflecting a face.”

The poem below, “Aubade,” exists within a similar terrain of loss and displacement, yet Tanaka describes this poem as a departure from many of the others in the collection. “Instead of putting on another persona, I began with myself in the most immediate surroundings,” he writes in an essay for Poetry Society of America. As he began writing, he attempted to ground himself in the immediacy of the sensations of his hip bones and kneecaps; soon, though, his mind drifted to an imaginary scene inspired by the Japanese Buddhist legend of Sanzu no Kawa, the mythical river that separates the living and the dead. As he reflects, “I had started alone in my room, writing; then somehow, I found myself in a mythic, ancestral, and communal space, one that feels emblematic of Chronicle of Drifting.”

In the midst of the collection’s landscape of loneliness and dislocation, “Aubade” testifies to the acts of care and communion that are still possible—and the ways that silence and stillness can facilitate this connection. As Tanaka writes in “Discourse on Vanishing,” “The earth stays still again. / This is not the end of the broken world.”

–Sarah Fleming

I sit on a chair and the chair touches me back.

According to my chair, I have two hips

and bones inside them hard as peach pits.

The femurs connected to the pelvis

lead to the kneecaps. I have kneecaps.

In the ancient past of my village, people used them

as drinking cups: a boy sipping sake

from the kneecap of grandfather,

whose kneecap is bigger than grandmother’s.

She helps her son detach the kneecap from the leg

and wash it in the stream. White of the kneecap,

she thinks, is trembling like a moon.

Funny it smells sweeter than the knee of the man

she remembers. When he was alive,

he wasn’t much of a man—thin, boneless,

his shoulder soft as a berry-bearing ivy.

Funny he seems more alive now,

this trembling bone under the cold water.

♦

From Chronicle of Drifting, copyright 2025 by Yuki Tanaka, used by permission of Copper Canyon Press, www.coppercanyonpress.org.

![]()

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.

This article is only for Subscribers!

Subscribe now to read this article and get immediate access to everything else.

Already a subscriber? Log in.

Tekef

Tekef