Bacteria and Kosher and Organic Chicken

How do contamination rates for antibiotic-resistant E. coli and ExPEC bacteria that cause urinary tract infections compare in kosher chicken versus organic chicken? Millions of […]

How do contamination rates for antibiotic-resistant E. coli and ExPEC bacteria that cause urinary tract infections compare in kosher chicken versus organic chicken?

Millions of Americans come down with bladder infections or urinary tract infections every year, including more than a million children. Most cases stay in the bladder, but when the bacteria creep up into the kidneys or get into the bloodstream, things can get serious. Thankfully, we have antibiotics, but there is now a pandemic of a new multidrug-resistant strain of E. coli. Discovered in 2008, this so-called ST131 strain has gone from being unknown to now being a leading cause of bladder infections the world over and is even resistant to some of our second- and third-line antibiotics. What’s more, it’s been found in retail chicken breasts sampled from across the country, “document[ing] a persisting reservoir of extensively antimicrobial-resistant ExPEC isolates,” or bacteria—that is, the extra-intestinal pathogenic E. coli, including the ST131 strain—“in retail chicken products in the United States, suggesting a potential public health threat.” I discuss this in my video Friday Favorites: What About Kosher and Organic Chicken?.

Urinary tract infections may be foodborne, predominantly from eating poultry, such as chicken or turkey, so maybe we shouldn’t be feeding antibiotics to these animals by the tons in poultry production. Hold on. Foodborne bladder infections? What are you doing with that drumstick? Indeed, eating contaminated chicken can lead to the colonization of the rectum with these bacteria that can then, even months later, crawl up into the bladder to cause an infection.

“The problem of increasing AMR [anti-microbial resistance] is so dire that some experts are predicting that the era of antibiotics may be coming to an end, ushering in a post-antibiotic era…in which common infections and minor injuries can kill” once again. More than 80 percent of E. coli isolated from beef, pork, and poultry exhibited resistance to at least one antibiotic, and more than half isolated from poultry were resistant to five different drugs. One of the ways this happens is that viruses, called bacteriophages, can transfer antibiotic-resistant genes between bacteria. About a quarter of these viruses isolated from chicken were found to be able to transduce antibiotic drug resistance into E. coli. And one of the big problems with this is that “disinfectants used to kill bacteria are, in many cases, not able to eliminate bacteriophages,” these viruses. Some of these viruses are even resistant to bleach at the kinds of concentrations used in the food industry; likewise, alcohol, which is found in many hand sanitizers, is also unable to harm most of them.

The irony is that the industry has tried to intentionally feed these viruses to chickens. Why would it do that? They can boost egg production in hens and increase bodyweight gain in broiler (meat-type) chickens to get them to slaughter weight faster. The only thing that seems to dissuade the industry is any practice that affects the taste of the meat. That’s why the industry stopped spraying chickens with benzene to try to kill off all of the parasites. The meat ended up with a “distasteful flavor,” described as “strong, acidic, musty, medicinal, biting, objectionable, and good.” Good?!

What about organic chicken? For another type of bacteria, Enterococcus, antibiotic-resistant bugs were found in both conventional and organically raised chicken but were less common in organic. A study found that only about one in three organic chickens were contaminated with drug-resistant bugs compared to nearly one in two conventionally raised birds. But in a study of hundreds of prepackaged retail chicken breasts tested from 99 grocery stores, carrying the organic or antibiotic-free label did not seem to impact the contamination levels of antibiotic-resistant E. coli from fresh retail chicken. Purchasing meat from natural food stores appeared to be safer, however, regardless of how it was labeled.

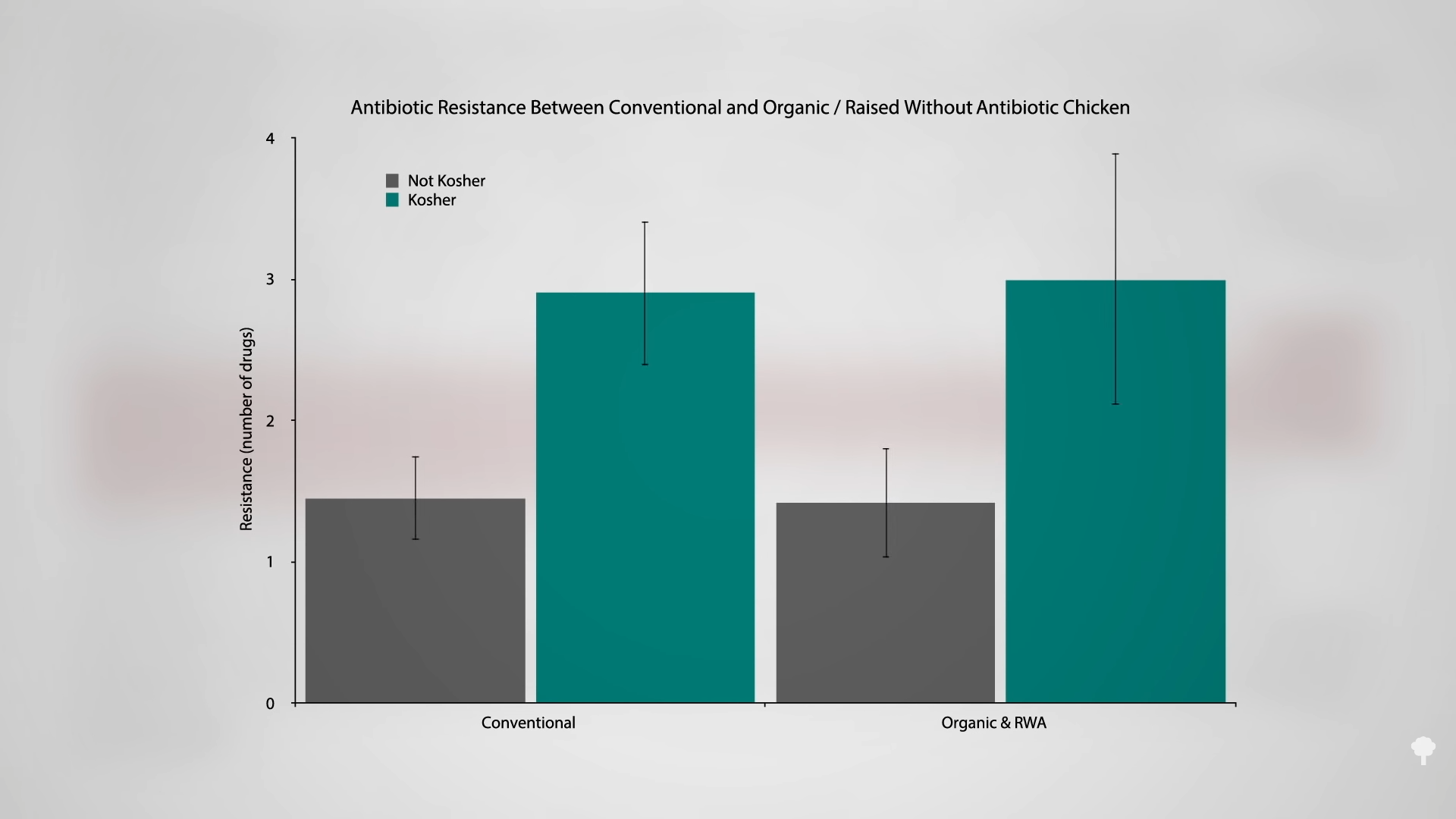

Kosher chicken appeared to be the worst, with nearly twice the level of antibiotic-resistant E. coli contamination compared to conventional chicken, which goes against the whole concept of kosher. As you can see in the graph below and at 4:17 in my video, there was no difference in drug resistance between the E. coli swabbed from conventionally raised chickens versus chickens raised organically and without antibiotics, but, either way, kosher was worse. But how could organic and raised-without-antibiotics chickens not be better? Well, it could be cross-contamination at the slaughter plants, so bugs just jump from one chicken carcass to the next.

Or it could be the organic chicken loophole. USDA organic standards prohibit the use of antibiotics in poultry starting on day two of the animal’s life. “This is an important loophole” because even antibiotics “considered critical for human health” are routinely injected into one-day-old chicks and eggs, which has been directly associated with antibiotic-resistant foodborne infections.

What’s more, there was no difference in the presence of ExPEC bacteria—the bacteria implicated in urinary tract infections—between organic and conventional chicken. “These findings suggest that retail chicken products in the United States, even if they are labeled ‘organic,’ pose a potential health threat to consumers because they are contaminated with extensively antibiotic-resistant and, presumably, virulent E. coli isolates.” Indeed, even if we were able to get the poultry industry to stop using antibiotics, the contamination of chicken meat with ExPEC bacteria could still remain a threat.

Hollif

Hollif