Toshiko Takaezu’s Hidden Worlds

The innovative ceramist fused traditional techniques with avant-garde aesthetics to create works that defy description. The post Toshiko Takaezu’s Hidden Worlds appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

When ceramist Toshiko Takaezu (1922–2011) was asked if she considered herself an artist, she responded that being an artist goes beyond the question of painting or making pots. “An artist is a poet in his or her own medium,” she answered. “And when an artist produces a good piece, that work has an unsaid quality; it contains a spirit and is alive. There’s a nebulous feeling in the piece that cannot be pinpointed in words.”

This unsaid quality animated much of Takaezu’s own work, and she herself could be difficult to pinpoint: As a ceramist and weaver, she worked at the intersection of pottery, sculpture, painting, and fiber arts, and her installations often defied categorization. Merging pottery and painting, she viewed her ceramic forms as three-dimensional canvases that concealed hidden worlds within—in Takaezu’s words, “the dark space you cannot see.”

Though Takaezu was a leading figure in experimental ceramics, she went largely unrecognized in the art world during her lifetime, as ceramics and fiber arts were considered minor disciplines and relegated to the realm of crafts. In the decade since her death, her work has received more mainstream attention—several of her pieces featured in the 2022 Venice Biennale, and she is currently the subject of two major retrospective exhibitions, including “Toshiko Takaezu: Worlds Within,” currently on view at the Noguchi Museum in Queens and slated to tour the United States over the next several years.

The largest retrospective of her work to date, “Worlds Within” follows seven decades of Takaezu’s vast and far-reaching career, from her initial student exhibitions to the large-scale immersive installations of her final years. Featuring roughly 200 of Takaezu’s ceramic forms, acrylic paintings, weavings, and bronze-cast sculptures, the exhibit tracks her development as an interdisciplinary artist as she melded traditional and avant-garde approaches, integrating Japanese pottery techniques, abstract expressionist painting, and the landscapes of her birthplace of Hawaiʻi. Honoring Takaezu’s careful attention to place, the retrospective presents several of her exhibitions as they were displayed in her lifetime, positioning her paintings and ceramic forms in conversation with one another as she originally envisioned.

Born the sixth of eleven children to Okinawan immigrant parents, Takaezu grew up in rural Hawaiʻi during the Great Depression. At the age of 15, she dropped out of high school to take a job as a housekeeper in Honolulu for the founders of the Hawaiʻi Potters’ Guild, and during World War II she began working at the guild, learning to make domestic products like ashtrays and casserole pans. Around this time, the University of Hawaiʻi at Manoa was starting up a ceramics program, and after the war Takaezu became one of its first students, entering its burgeoning scene of Asian American modernist artists. There, she began her lifelong exploration of nonfunctional vessel shapes, moving beyond the utilitarian items she produced at HPG to create forms that tested the limits of her field.

In 1951, Takaezu left Hawaiʻi to enroll at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, where she studied with the Finnish ceramist Maija Grotell and honed her artistic voice. “Hawaiʻi was where I learned technique,” she commented. “Cranbrook was where I found myself.” Under the joint tutelage of Grotell and the Finnish weaver Marianne Strengell, Takaezu began to bring weaving and pottery into conversation with each other, as seen in the Noguchi’s recreation of one of her first student exhibitions where woven runners sit side by side with her minimalist bowls and plates. Takaezu’s biggest takeaway from her time studying with Grotell was that her freedom was her biggest strength, and she began venturing further into abstract forms to try to find her own style as a potter.

To further develop her voice and learn more about her own roots, in 1955, Takaezu set out on an eight-month trip to Japan with her mother and sister so she could immerse herself in Japanese artistic culture and visit her mother’s ancestral home. After traveling to Okinawa to meet her mother’s family, she continued on to Kyoto, where she sought out the work of prominent potters from the classical to the avant-garde, including the 19th-century Buddhist nun, poet, and painter Otagaki Rengetsu and the experimental ceramist Yagi Kazuo, who cofounded the experimental ceramic collective Sodeisha (“Crawling through Mud Association”). Through studying with the master potter Kaneshige Toyo, she learned 16th-century Bizen ware techniques, which she went on to incorporate in novel and inventive ways.

While in Kyoto, she and her sister also lived and studied at Chotoku-in, a Zen temple in the Shokoku-ji monastery complex. She also embarked on learning chado, or the way of tea, so that she could better understand how to make tea bowls. This was a spiritual preparation as much as a technical one: Chado was not just “a question of technique, it was a question of being ready as a person.” In her view, the spiritual cultivation of chado was a necessary precursor to artistic development.

Though many critics later tried to cast Takaezu as a Zen potter—the artist John Perreault noted that she has often been seen as “a kind of priestess of clay, a nun of earth and fire, a female monk”—she herself resisted this label, fearing that it would constrain her: “I have no connections to Zen,” she told one interviewer. “If you start thinking of Zen, you stifle yourself.” Still, her approach to her work bears some resemblance to the Zen aesthetics and philosophy she encountered on her trip, particularly in the continuity between art, spiritual practice, and everyday life. In fact, her biggest revelation from her stay at Chotoku-in was how thoroughly her mother embodied “the life of Zen” in the way she conducted her daily activities. Takaezu carried this spirit into her own work as well, seeing much of her daily life as an extension of her aesthetic practice, and vice versa: She once told an interviewer, “In my life I see no difference between making pots, cooking, and growing vegetables.” (She later added, “I think sometimes my potatoes are more important than my pots.”) Later in life, she would sometimes cook chicken and dry mushrooms in her kiln, and she often displayed her clay forms in her gardens, nestled among her tomato plants.

Left to right: 1. Toshiko Takaezu, Closed Form, undated. Porcelain, 12 x 7 in. (30.5 x 17.8 cm). Private Collection. 2. Toshiko Takaezu, Sweet Potatoe, 1981. Stoneware (wood fired by Katsuyuki Sakazume at the Anagama Project, Peters Valley, New Jersey), 39 × 25 × 17 in. (99.1 × 63.5 × 43.2 cm). Collection of Jeff Schlanger and Anne Humanfeld. 3. Toshiko Takaezu, Closed Form, 2004. Porcelain, 19 1/2 x 11 in. (49.5 x 27.9 cm). Private Collection. Photo: Nicholas Knight. Courtesy the Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum. © Family of Toshiko Takaezu

Left to right: 1. Toshiko Takaezu, Closed Form, undated. Porcelain, 12 x 7 in. (30.5 x 17.8 cm). Private Collection. 2. Toshiko Takaezu, Sweet Potatoe, 1981. Stoneware (wood fired by Katsuyuki Sakazume at the Anagama Project, Peters Valley, New Jersey), 39 × 25 × 17 in. (99.1 × 63.5 × 43.2 cm). Collection of Jeff Schlanger and Anne Humanfeld. 3. Toshiko Takaezu, Closed Form, 2004. Porcelain, 19 1/2 x 11 in. (49.5 x 27.9 cm). Private Collection. Photo: Nicholas Knight. Courtesy the Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum. © Family of Toshiko TakaezuAfter her trip to Japan, Takaezu returned to the US reenergized and inspired to put into practice the techniques she had learned. Fusing the traditional and the avant-garde, Takaezu experimented with nonfunctional forms, like multispouted vessels, mask pots, and stacked ovoid shapes, before eventually arriving at her signature closed form (a sealed vessel with only a small vent to release air in the firing process). Over the course of her career, Takaezu continued to iterate on these forms, creating abstract vessels inspired by human torsos, peaches, hearts, eggs, sweet potatoes, and tamarind seed pods.

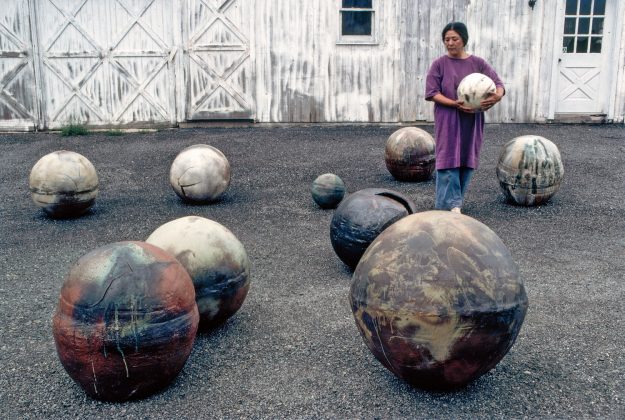

One of her most distinctive forms was her series of moon pots, spherical orbs inspired by the Apollo moon landing that she described as “rounder than round.” After joining together two bowls at the rim, she would beat each moon with a paddle to introduce asymmetry. The moons sometimes fractured in the firing process as well, creating further irregularities and imperfections. To give these orbs a sense of movement, she often mounted them on volcanic rock or suspended them midair in woven hammocks, which the Noguchi has replicated so viewers can engage with the moons as Takaezu intended.

Toshiko Takaezu, Gaea (1979–) at LongHouse Reserve, East Hampton, New York, June 19–September 1994. Toshiko Takaezu Archives. © Family of Toshiko Takaezu

Toshiko Takaezu, Gaea (1979–) at LongHouse Reserve, East Hampton, New York, June 19–September 1994. Toshiko Takaezu Archives. © Family of Toshiko TakaezuTakaezu was fascinated by the interiority of these closed forms, which she described as the “life energy” inside her pieces. Viewing this energy as the most important part of her work, she continually experimented with how to draw attention to the hidden worlds within each form. Inspired by the Buddhist nun Rengetsu, who carved her tanka and haiku onto her pots, Takaezu sometimes wrote inside her vessels before sealing them up, knowing that viewers would never be able to read her words.

Eventually, she discovered another unseen dimension of her work, this time by accident: After a scrap of clay fell into a closed vessel and inadvertently created a rattle sound, she began placing small clay beads into her pieces to produce a variety of sonic effects. “Some sound like grasses rustling in the wind,” she wrote, “some like waves breaking on the shore.” Takaezu described these sonic worlds, revealed only through touch, as “sending messages.” To highlight these hidden soundscapes, the museum offers daily guided touch tours, where visitors are encouraged to gently play with a selection of Takaezu’s closed forms. One gallery also features a short film by Leilehua Lanzilotti, a Kanaka Maoli sound artist and composer who has studied the influence of Hawaiʻian landscapes and indigenous culture on Takaezu’s work. Titled the sky in our hands, our hands in the sky, the film overlays recorded sounds of Takaezu’s closed forms with footage of Hawaiʻian volcanoes and mountain ranges, giving the viewer a sense of Takaezu’s full multisensory environment.

Toshiko Takaezu with moons, 1979. Photo: Hiro. Toshiko Takaezu Archives. © Family of Toshiko Takaezu

Toshiko Takaezu with moons, 1979. Photo: Hiro. Toshiko Takaezu Archives. © Family of Toshiko TakaezuThough Takaezu never returned to Hawaiʻi after her initial departure for more than a year at a time, its environment continued to shape her work: “You can see the color in my pots—the color of the ocean, the sky, the sunset,” she reflected. She often used natural materials from Hawaiʻi, including volcanic black sand and local plant fibers, and her glazes were inspired by the vibrant colors of the islands’ seascapes. Some of her work was made in direct response to her travels on the islands—the moons, for instance, were inspired by lava fields near the Halemaʻumaʻu crater that NASA astronauts used to train for lunar exploration. This impact became more explicit in her later work, including her tree forms, which she created after visiting Devastation Forest, the acres of wildlife destroyed by the 1959 eruption of Kilauea Iki. Inspired by the silhouettes of scorched trees suspended in lava fields, she developed large-scale installations like Homage to Devastation Forest and Lava Forest. With these projects, she drew attention to the destruction and renewal inherent in the life cycle, as well as in her own artistic process—she described the organic material of ceramic forms as “dying” in the first part of firing, only to return to life through glazing. For her, there was a sense of synergy between pottery and her own environment, and each pot contained the life cycle in miniature: “One can feel the whole cycle of growth and life and death in pots, just as this cycle is present in the garden.”

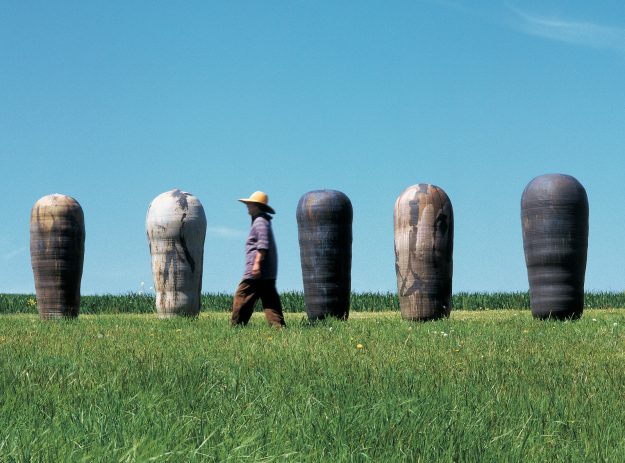

Toshiko Takaezu with works later combined in the Star Series (c. 1994–2001), including (from left to right) Sahu, Nommo, Emme Ya, Unas, and Po Tolo (Dark Companion), 1998. Photo: Tom Grotta. Courtesy of browngrotta arts. © Family of Toshiko Takaezu

Toshiko Takaezu with works later combined in the Star Series (c. 1994–2001), including (from left to right) Sahu, Nommo, Emme Ya, Unas, and Po Tolo (Dark Companion), 1998. Photo: Tom Grotta. Courtesy of browngrotta arts. © Family of Toshiko TakaezuAs Takaezu herself grew older, she turned increasingly toward works that were cosmic in scale, creating pieces larger than her own body that often required scaffolds and multiple assistants to produce. In developing these monumental forms, she sought a sense of vastness and surfaces “on which to paint with a feeling of freedom.” The culmination of this quest was her Star Series, a collection of fourteen closed forms, each taller than Takaezu herself, named after celestial bodies. Five of these forms are currently on display at the Noguchi, and they inhabit perhaps the most striking room of the exhibit. Positioned in a formation inspired by Takaezu’s own arrangement, the irregular cylindrical vessels exert an almost gravitational pull, drawing the viewer in. This mirrors Takaezu’s own experience in crafting these colossal works: “When I’m building one of the enclosed forms and I’m up there on a scaffold and the wheel is moving, there’s an almost psychic feeling that I’m going to be pulled into the pot…. It’s a fantastic sensation. My heart pounds. It’s strange even to talk about it. There I am on top, and when I look down, it’s as if the whole universe is right inside the pot.”

Takaezu recognized the power that her work could exert, and she attributed this power to a force beyond herself, an “intangible source that I can’t pinpoint.” Perhaps the power of Takaezu’s art lies in her palpable commitment to its mystery—that unsaid quality she prized above all—and her wholehearted devotion to her craft. Reflecting again on critics’ labeling her work as Zen, she once told an interviewer, “If there is Zen in it, or whatever it is, it comes through if you enjoy doing your work. Anything you do with the best of your capacities is beautiful…Your whole body gets to be a part of everything, and you become free.”

Lynk

Lynk