Biden is still trying to forgive student debt in 'a very direct confrontation' with Supreme Court, expert says

President Joe Biden is still trying to forgive student debt after the Supreme Court ruled that his first attempt to do so was not legal.

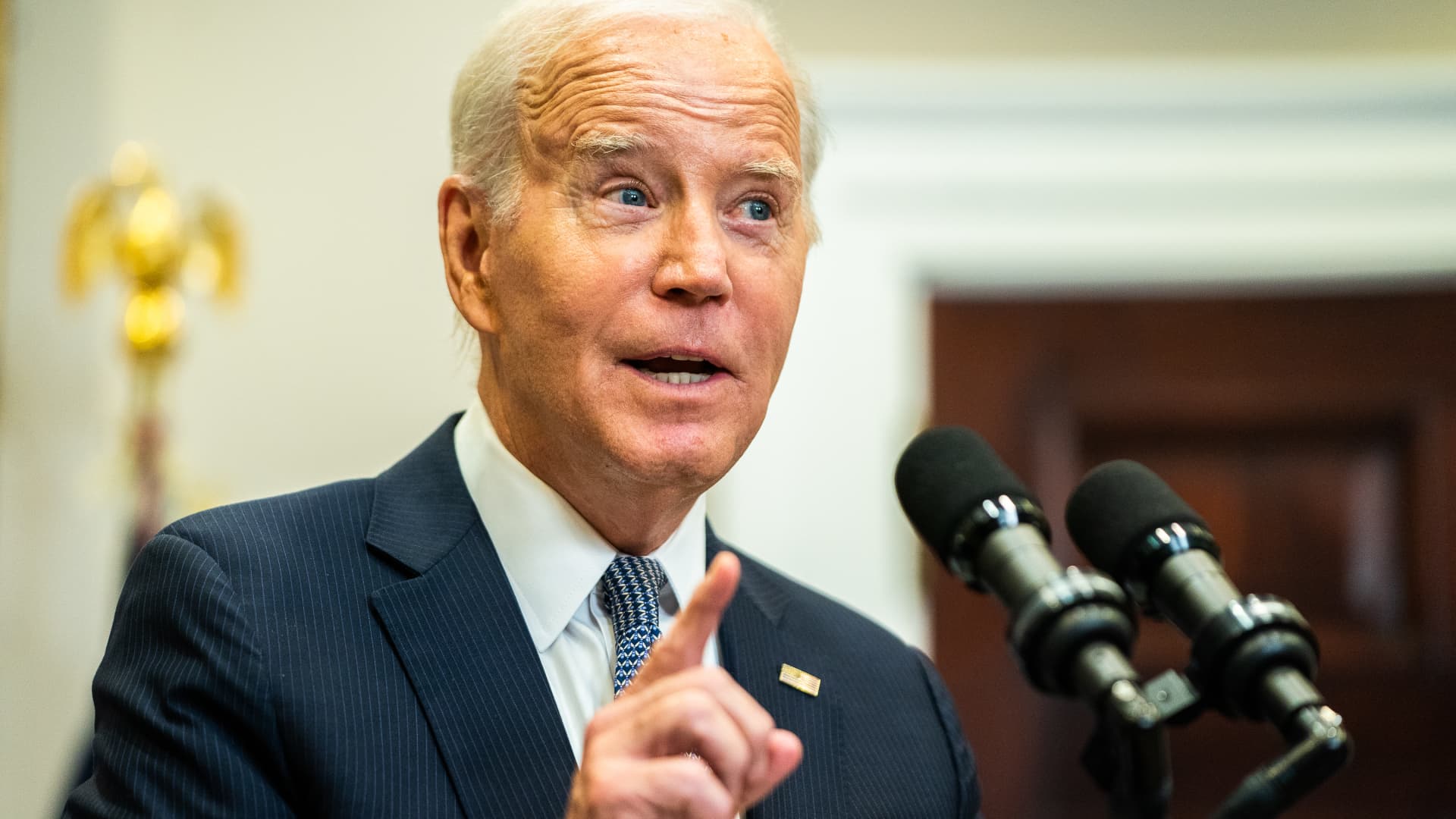

President Joe Biden delivers remarks on the Supreme Court's decision on the Administration's student debt relief program at the White House on June 30, 2023.

The Washington Post | The Washington Post | Getty Images

After the Supreme Court struck down the original White House federal student loan forgiveness plan earlier this year, legal historian Noah Rosenblum was struck by President Joe Biden's response.

As far as Rosenblum could determine, Biden was saying that the justices were wrong in their ruling.

What's more, the assistant law professor at New York University said, the president announced he would try to pursue the same goal under a different law.

"This is a very direct confrontation with the Court," Rosenblum wrote at the end of June on X, the social media platform formerly known as Twitter.

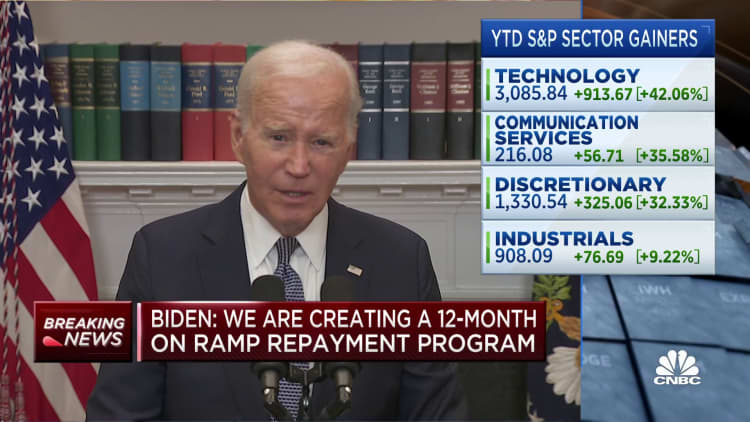

Indeed, just hours after the justices blocked Biden's plan to cancel up to $20,000 in student debt for tens of millions of Americans, Biden delivered remarks from the White House in which he said that "today's decision has closed one path. Now, we're going to pursue another."

CNBC interviewed Rosenblum this month about Biden's Plan B for student loan forgiveness and the uniqueness of his stance toward the high court.

(The exchange has been edited and condensed for clarity.)

Annie Nova: What exactly did you find so bold about President Biden disagreeing with the Supreme Court and announcing another plan to forgive student debt?

Noah Rosenblum: Mainstream Democrats have generally been reticent to criticize the Supreme Court, even as it has aggressively pursued unpopular Republican policies. So the first striking thing was that Biden was striking back against the court at all. But I was also struck by how Biden decided to push back. Rather than hide behind mystifying legalese, he framed the issue clearly and simply. As he explained it, his administration had taken democratic action and the court had tried to usurp its power and stop it from acting. It was because of the court, Biden made clear, that Americans would not receive the relief his administration had sought to provide them. And Biden said he would not allow the court to get the last word in expounding the meaning of the law.

AN: Why do you think there's hesitation to challenge the justices?

NR: It think it is the result of a misreading of the famous events of 1937, in which Franklin Roosevelt positioned himself as an adversary to the court. Famously, the court of the early 1930s had struck down New Deal legislation. In response, Roosevelt threatened to appoint additional justices if it did not change course. Of course, the court did change course, making Roosevelt's plan unnecessary, and he dropped it. But a narrative has taken hold that Roosevelt's threat was bad politics. I think this narrative is mistaken. While there is persuasive evidence that the court may have been changing its opinion of New Deal legislation before Roosevelt issued his threat, the threat achieved what it aimed at. Before Roosevelt, conflict between the Supreme Court and the president was not taboo, and Supreme Court justices were often understood to be important ordinary political figures. Charles Evans Hughes, chief justice of the Supreme Court when Roosevelt was elected, had been a Republican candidate for president.

AN: What did you find most surprising about the Supreme Court's decision on Biden's forgiveness?

NR: At the end of the day, it was a very narrow ruling. While the case has important consequences for standing doctrine and for the ability to challenge the provision of government benefits, the case swept much less widely than it could have and than many commentators expected.

Biden said he would not allow the court to get the last word.

AN: Some legal experts expect Biden's second attempt to forgive student debt to conclude with another death at the Supreme Court. Do you predict the same?

NR: As a legal matter, I think it should go differently. The process for forgiving debt under the new plan is longer and more elaborate, but the Education secretary's authority to cancel debt at the end of it is clearer than it was under Biden's first plan. Whether it will go differently is a separate question. Assuming the Biden administration is able to bring its work to completion, I think the court will have a much harder time striking down the forgiveness under Plan B. But I suspect that there will be several Republican-appointed justices on the court who will try to find a way to invalidate the administration's actions anyway. And we have to remember that the conservatives have six votes at the moment and have been willing to ignore long-settled legal principles to achieve Republican policy priorities.

AN: Why do you think there's so much pressure on the government to address student debt?

NR: For many years, policy relied on increasing access to higher education as a path to economic mobility and ignored that growing inequality. The terrible consequences of that policy choice are coming home to roost. In a society as unequal and unfair as ours, a college degree is no longer a guarantee of a secure financial future. Many Americans now owe thousands of dollars, even as they find themselves under the shoe of an unfair economic system and unable to earn enough money to pay it back, nevermind achieve the economic mobility they were promised. The student loan debt system is in crisis in the same way that many other features of our economy that disproportionally affect the nonrich are in crisis, including housing and health care.

KickT

KickT