Buddhist nun Ayya Khema was a force of nature — and of unconditional love

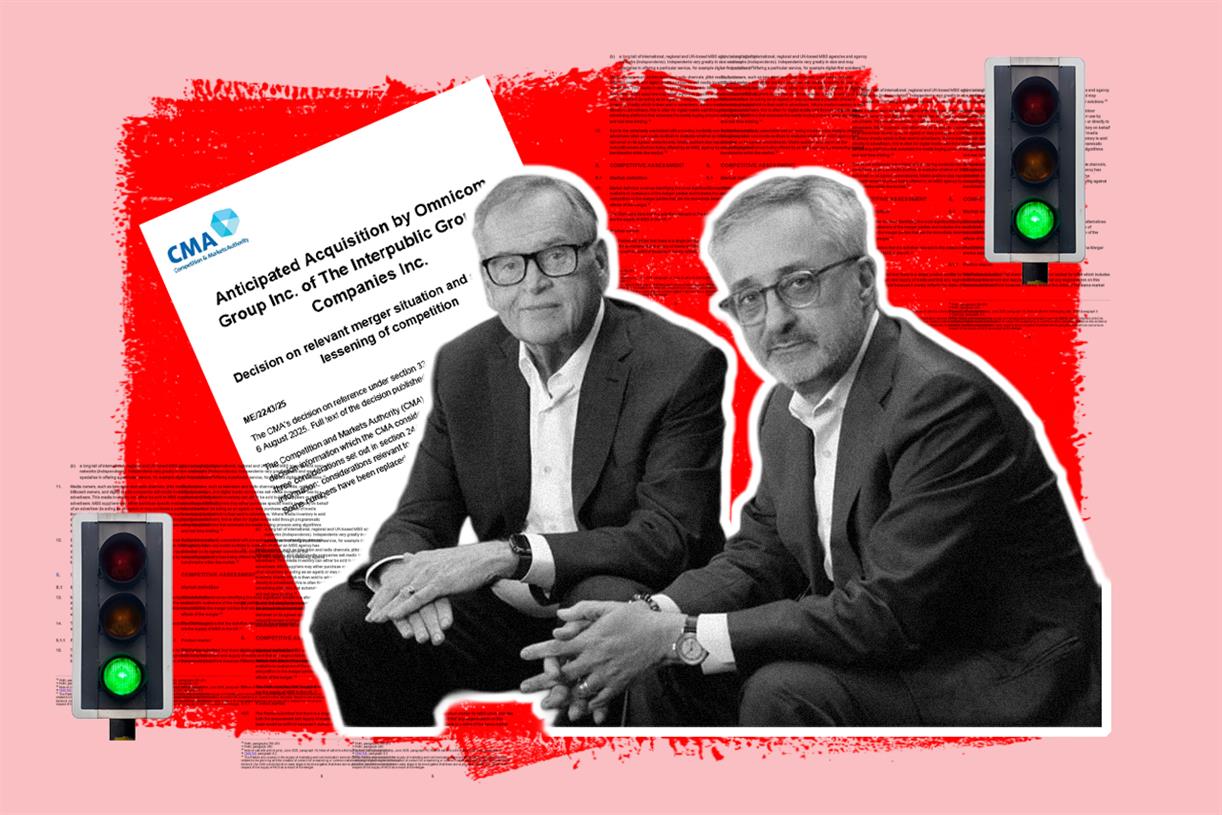

Lion's Roar's Rod Meade Sperry talks to Leigh Brasington about a new posthumous release from Ayya Khema, "The Path to Peace: A Buddhist Guide to Cultivating Loving-kindness." The post Buddhist nun Ayya Khema was a force of nature —...

Lion’s Roar’s Rod Meade Sperry talks to Leigh Brasington about a new posthumous release from the pioneering Buddhist nun Ayya Khema, The Path to Peace: A Buddhist Guide to Cultivating Loving-kindness.

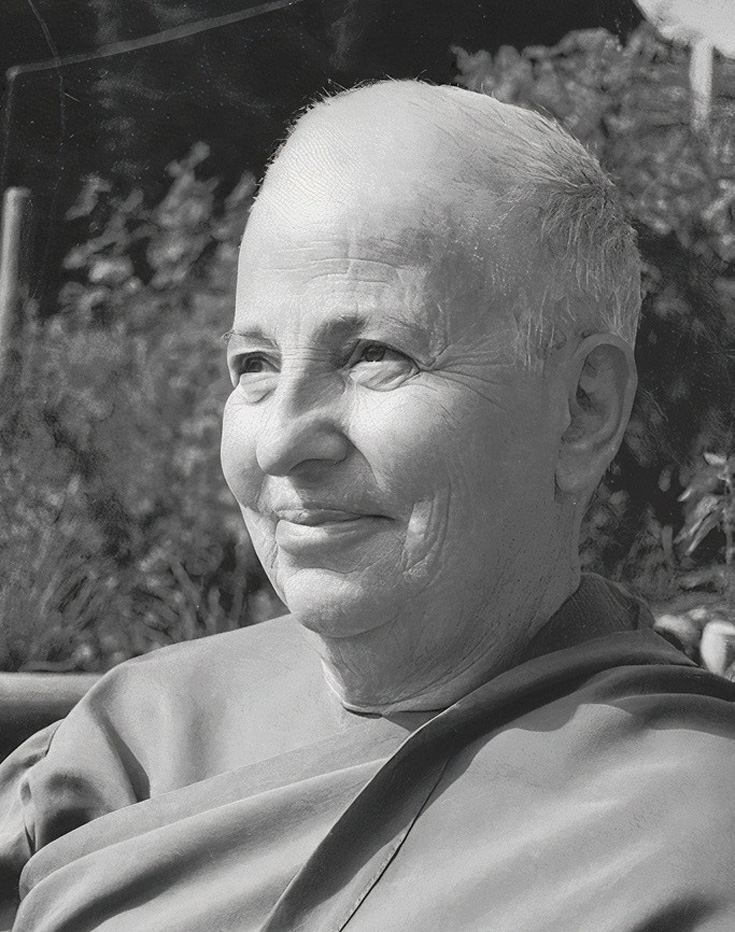

Ayya Khema. Photo courtesy of Leigh Brasington.

New in Buddhist books is The Path to Peace: A Buddhist Guide to Cultivating Loving-kindness (Shambhala Publications), a new posthumous release from the trailblazing Buddhist nun and teacher, Ayya Khema (1923-1997). The book was edited by Leigh Brasington, who has first-hand knowledge of the “force of nature” that was Ayya Khema, having practiced and trained with her.

Leigh recently sat down with me for a Lion’s Roar Podcast interview about the book, Ayya Khema, her adventurous life, and her teachings on metta, or loving-kindness. That complete interview will be released here in the days ahead, and will include a guided “metta visualization” practice, led by Brasington, in the Ayya Khema style. You won’t want to miss that; it’s a lovely practice, and in fact, Leigh has a hunch that it was Ayya Khema’s personal favorite.

For now, though, here are some excerpts from our discussion about Ayya Khema’s teachings on metta and her adventurous life.

Rod Meade Sperry: Leigh, welcome. Thank you so much. Great to have you on the podcast.

Leigh Brasington: Thank you. I really appreciate being here and getting a chance to talk about this book.

For those who do not know, who was Ayya Khema, and what made her so unique? Because unique, she certainly was.

She was a German Jewish Theravada nun, a Buddhist nun. She was born in Berlin in 1923. So she was 10 when Hitler came to power, she was sent on the last kinder transport, the last transport of Jewish children out of Germany. When she was 15, she went to Scotland where she had some relatives and in 1941, she took a Japanese freighter from Scotland to Shanghai where her parents had escaped. And this was before Pearl Harbor, but the freighter could have been sunk by either side.

She lived in Shanghai during the war. And it was actually pretty nice at first, until the Japanese threw all Westerners in a concentration camp. Her father died during that. And she was liberated by the Americans in ’45, came to the US, was married, had a couple kids.

Her husband was an engineer and got a posting to Pakistan; I’ve forgotten whether it was a bridge or an aqueduct or something like that he was working on. And when they finished, they drove from Pakistan to London in a Land Rover. Now this is the early 60’s, before people were doing anything like this. She led an adventure-filled life.

And after they were in London for a while, they drove back to India, where she first encountered Hindu meditation. They then settled in Queensland, Australia on an organic farm and she continued her meditation practice. She didn’t really really have a connection with it until one of her neighbors said, would you like to hear a talk by a Buddhist monk? And she went to that and she knew she was home.

She was brilliant. And so amazingly clear. She could express very deep ideas in a way that was so highly accessible.

And she began practicing Buddhist meditation. The monk was Venerable Khantipalo, and she would attend his retreats and got really good at the meditation stuff. And he eventually had her assisting on his retreats. She came back from teaching one retreat and her husband had left saying, basically, she was more interested in this Buddhism stuff than him, and he was out of there. She was rather upset about that, but she had to admit: he was correct.

So eventually she was living in Sri Lanka and decided to ordain as a nun there. At that time, women could only get 10-precept ordination, not full ordination, but Ayya Khema was, well, a force of nature. You were not gonna stop her by telling her she couldn’t become fully ordained. So after she was a 10-precept nun, she came to visit her daughter in San Diego and then went to the Chinese Chan Zen temple in LA and got full ordination. And then she went back to being perhaps the first, fully ordained Theravada nun in a thousand years.

She managed to convince a number of other Sri Lankan women to get full ordination, and basically was one of the people that has revived full ordination for Theravada nuns.

She taught retreats. She actually had a retreat center that she ran for a number of years on an island in Sri Lanka, until the civil war there just made it too difficult. She moved back to Germany; she founded a retreat center and eventually a monastery there.

And all this time, she’s teaching retreats. She would go to Australia, teach retreats there. And she would come to California, which is where I first encountered her.

Ayya Khema and Leigh Brasington. Marin County, Calif, USA, July 1996. Photo courtesy of Leigh Brasington.

What was it about her?

She was brilliant. And so amazingly clear. Anyone you talked to about her, one of the first things they’re gonna tell you about her was her clarity and how she could really express these very deep ideas in a way that was so highly accessible. She died in 1997.

And so November will be the 25th anniversary of her death, but she’s still publishing material because she was that brilliant a teacher.

And next year will be the hundredth anniversary of her birth.

Right! Exactly. So we have two anniversaries coming up.

What are the processes and considerations that went into making The Path to Peace?

The number one consideration was to preserve Ayya Khema’s voice. As I said, she had remarkable clarity, but she had an idiosyncratic way of speaking. German was her first language. She learned English in Scotland as a teenager, and then she lived in Australia and then, I mean, she spent time in America and lived in Australia.

The book arose because one of my students had heard these talks multiple times and asked me, if I do a transcription of these talks, can you convert it into a book? Diana Gould, the student who asked this of me, knew what was involved, because she is an award-winning published author.

She provided me with the transcripts and I already had a transcript of another talk of hers. And so I put it together and edited it down, trying to preserve Ayya Khema’s way of teaching, her idiosyncratic way of talking, and yet make sure that what she was saying came across. Basically this is what you would hear from Ayya Khema.

How much time did you get to spend with her?

I was her student for 12 years. I met her in 1985. One of my friends said that I should go on a retreat. And I was like, yeah, yeah. And then she said, well, there’s gonna be this retreat. The teacher’s giving a talk at the San Francisco Zen Center. You should go listen to it. And if you like her, sign up for the retreat. Well, since I was unemployed at the time, it was like, okay, and I went and it was Ayya Khema. I don’t remember what that first talk was about, but I do remember the clarity. So I signed up for the retreat and went off to the desert for ten days.

What was it like?

I thought I had meditated before, but I quickly learned from Ayya Khema that what I had been doing for meditation wasn’t what she considered meditation. I didn’t re-encounter her for the next five years. And then one of my friends handed me a flyer and said, you wanna go to a retreat? And it was Ayya Khema. So I signed up and went along for another 10 day retreat. She was my first teacher. The next year’s retreat was a one week retreat followed by a one month retreat. A year later, I had a month with her; a year after that she had breast cancer and had surgery and I was unable: she didn’t teach a retreat that I could attend. The year after that she came back to California and taught a 24 day retreat. But because of the breast cancer surgery, she just didn’t have the energy she had before.

She was amazing. She’d have a retreat of maybe 40 students and give everybody one on one interviews multiple times during the retreat, but she didn’t have the energy for it anymore. So when I showed, she said, oh, you’re gonna be helping with the interviews. And I go, I don’t know how to do interviews. She said, you’ll learn.

And she put me to work, basically learning how to be a teacher, helping her with the interviews for that 24 day retreat. And that was really remarkable. And then she was back two years later for a one-week retreat. And at that one, she basically had me and one other of her advanced students do all of the interviews because she just really didn’t have the energy for it.

“The Path to Peace: A Buddhist Guide to Cultivating Loving-Kindness”

By Ayya Khema; Edited by Leigh Brasington

Shambhala Publications, 2022

It sounds like her final days were approaching.

That was in ‘96, and she died a little over a year later. I did get to see her three weeks before she died. She knew she was dying.

This was in Germany and, yeah, she was totally unconcerned about dying. It was like, “yeah, my body’s given out; time to go.” What she wanted to do was talk about the dharma and how I should go about teaching it. I learned so much.

You said that you were sort of disabused of what your notion of meditation was when you did that first retreat with her. Can you say something about what your idea originally had been, and how it changed from this experience?

My original idea was, you sit down and you think about something — just, you know, whatever you wanna think about. Just sit there quietly and think. Don’t move and think. That’s not meditation, but that’s what I had assumed it was. With Ayya Khema, the first instructions were for mindfulness of breathing: Sit there. Don’t think. And you know, if the thinking shows up, if you get distracted, label the distraction, a one word label. And then come back to the breathing.

A one-word label, said internally, like “thinking” or something like that?

More like “planning,” “worrying,” wanting a little more specific than “thinking,” but just some idea of it to give you a chance to really begin to get some insight into where your mind habitually goes.

As she said: Does it usually go to the past, or the future? And notice how infrequently we get distracted into the present, which is all we really have, as she put it. The past is a memory. The future is a fantasy. Pay attention to what’s going on here and now.

What kind of training or experience does one need for relating to The Path to Peace?

All you need for relating to this book is some idea of wanting to connect better with the other people that are in your environment, and that you’re sharing this planet with. That’s all that’s really necessary.

Now, metta is often defined as “loving-kindness” (a traditional translation) but Ayya Khema preferred the term “unconditional love.” Can you explain the difference as she saw it?

Yeah, I think she felt that “loving-kindness” didn’t really get at the heart of what the Buddha was teaching.

So: I’m a Presbyterian preacher’s kid. And so I grew up with Christianity as my spiritual practice and there, I learned the Greeks had a word for it. You know, Greeks had philos as brotherly love, eros as romantic love, and agape as spiritual love or unconditional love. And that was the love that Jesus was teaching.

And yeah, that’s what the Buddha is teaching: you’re to love someone just because they are someone, not because of what they do for you or could do for you or did for you in the past. It’s just that this is a person and they deserve to be treated with respect and if you can help them, you help them.

And if they have good fortune, you rejoice in their good fortune. It’s unconditional. There are no conditions that need to be met before you give this love, this metta. And so I think Ayya Khema’s translation as unconditional love is much, much more appropriate. Now, this doesn’t mean that with everybody you love, there aren’t conditions there, and you may find it much easier to love people when there are conditions, because this is someone you’re really close to and you really appreciate. But the idea is to cultivate for everyone that same feeling you have for someone that’s easy to love, to give that to everybody.

Both “unconditional love” and “loving-kindness” are wonderful phrases, evoking a lot. But they also sound like tall orders for the more cantankerous among us. In a way, we’re really just talking about being friendly and decent, right?

Yes, exactly. That’s how it starts: be friendly and decent. And as you get better at being friendly and decent, you can also be helpful and friendly and decent. And when someone has something positive happen, you can be happy that something positive happened to that person. In other words, you start out just being friendly and decent, but it’s possible to take it even further to the point where yeah, you’re wishing and sending good will towards everybody. Including the difficult people in your life.

This idea of wishing and “sending” metta for someone — if somebody’s never really encountered this before, they may be vexed by the meaning of “sending” here. What do we really mean by sending?

My favorite way of doing metta is basically to ask somebody, do you like to be happy? Most people like to be happy. Can you get in touch with the fact that you like to be happy? Most people can actually get in touch with the fact that they like to be happy. Do you like it if your friends are happy? Yeah, I like it if my friends are happy. Can you get in touch with the fact that you like it, that your friends are happy?

Can you appreciate the happiness of other people? If you can do that, then it sets you up so you can help them to be more happy.

What about your coworkers? Your neighbors? Can you get in touch with that? You like it that they’re happy? This is more what the “sending” is. Just get in touch with that sense of, yeah, I like it when the people I run into in the grocery store are all happy, when the clerk is happy, when my coworkers are happy, when the difficult people in my life are happy because they have wholesome sources of happiness. So it’s more about realizing that happiness is something that we all appreciate. And can you appreciate the happiness of other people? If you can do that, then it sets you up so you can perhaps at times help them to be more happy, help them when they’re feeling down or rejoice with them when they’re having good fortune. And this actually opens your heart. The whole purpose of this metta practice is to realize that we are vastly interconnected.

We’re not separate creatures. We’re social creatures. And we all rely on each other for everything, including our food, the electricity, everything that goes on in our lives. We’re relying on many other people. It’s a vastly interconnected network. Act in harmony with this interconnectedness, and that’s by making the interconnectedness work better for everyone.

For more on metta/loving-kindness, check out Lion’s Roar’s many articles, and listen for our complete interview with Leigh Brasington, coming soon on The Lion’s Roar Podcast, and featuring a guided metta visualization in the style of the late, great Ayya Khema.

And for more from Leigh Brasington, visit his website full of resources including another new book, Dependent Origination and Emptiness, freely downloadable.

KickT

KickT