Falling Angels

A Zen reading of Leonard Cohen’s life and art The post Falling Angels appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

A Zen reading of Leonard Cohen’s life and art

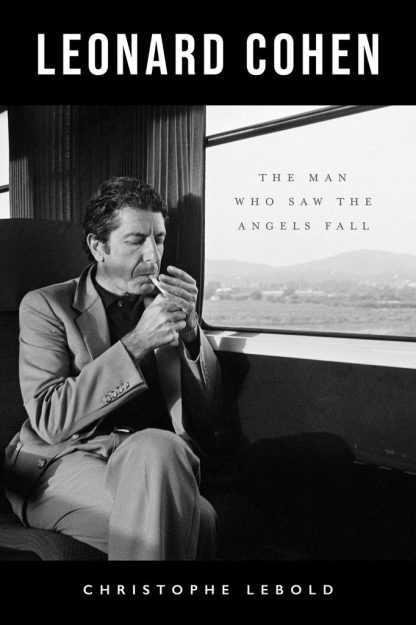

By Matthew Gindin Apr 06, 2025 Portrait of Canadian singer/songwriter and poet Leonard Cohen in Oslo, Norway, December 31, 1995. | Photo by Orjan Ellingvag / Alamy Stock Photo.

Portrait of Canadian singer/songwriter and poet Leonard Cohen in Oslo, Norway, December 31, 1995. | Photo by Orjan Ellingvag / Alamy Stock Photo.“I have so much love for Cohen’s work. I had to do something with it, or the love I had would be incomplete.” So Christophe Lebold told me over Zoom from a small room at the University of Strasbourg in France, where his shaven head, elegant but simple clothing, and intelligent, sensitive face highlighted against the bare white walls of the room helped to invoke a Cohen-esque atmosphere for our discussion. Lebold, who teaches classical and modern literature of North America and Britain and theater studies at the University of Strasbourg, is the author of a recently published book on Cohen called Leonard Cohen: The Man Who Saw the Angels Fall. The book went through two editions in French and was translated into English by the author in 2024.

It is an engaging, jazzily poetic, and erudite presentation of Cohen’s life and work as a modern rock ’n’ roll Kabir, a unique poet of defeat and transcendence, the love of God and the love of women, and the game of seeking enlightenment where only “beautiful losers” win. Lebold wrote his PhD on the songs of Cohen and Bob Dylan and regularly teaches the songs of singer-songwriters like Nick Cave and Lou Reed as literature. His keen powers of analysis and intense interest in his subject are evident on every page, and having taught and written about Cohen for years, I was in awe at how well-informed and up-to-date Lebold is with the available sources.

Leonard Cohen: The Man Who Saw the Angels Fall, by Christophe Lebold. ECW Press, 2024, 576 pp., $29.95, paper

Leonard Cohen: The Man Who Saw the Angels Fall, by Christophe Lebold. ECW Press, 2024, 576 pp., $29.95, paper

The book is dedicated to Cohen and Zen teacher Yoshin David Radin, who lives and teaches in the Santa Cruz area and who Lebold told me he considers an important “spiritual friend.” Lebold has been a Zen practitioner for over twenty years. He brings his understanding of the Zen tradition and a Zen sensibility to the book, writing with humor and an expansive embrace of the human condition and its existential paradoxes.

As Lebold writes in the book, Cohen’s interest in mysticism and spiritual discipline dates back to his teenage years, and his interest in Zen spanned decades, beginning long before he was ordained as a Zen monk on Mt. Baldy in the Rinzai lineage of Joshu Sasaki. Cohen started sitting sesshin in the early 1970s and lived as a monk for three years in the late ’90s. Regarding his meetings with Cohen, Lebold talks about Cohen’s deep and broad knowledge of the Zen tradition, which he thinks people often underestimate. Although when Lebold spent time with Cohen, in 2014, he was no longer a monk and sat zazen only occasionally, Lebold describes the way he would sit in lotus pose on the couch while chatting or offer incense formally to a statue of the Virgin Mary he kept in a cupboard with a gassho. “Zen was integrated into his being, part of how he lived his life.”

Lebold’s book is true to the complexity of its subject matter. It goes far beyond focusing on Cohen’s Zen, analyzing and discussing Cohen’s Jewishness and interest in the Jewish mystical tradition, and contains a fascinating discussion of Cohen’s life-changing transformation with the Advaita teacher Ramesh Balsekar in India late in his life. Throughout, Lebold’s primary focus is on Cohen’s life and work as spiritual art—which in Cohen’s sense does not, of course, mean “unworldly” or “nonsensual” art. Beyond Cohen’s explicitly spiritual preoccupations, Lebold reads Cohen’s life like a text, identifying key themes and movements, and weaves rich discussions around Cohen’s poems, songs, and prose writing throughout.

This is the first ‘big’ biography that puts Zen Buddhism in its rightful place in Cohen’s life.

“The aim was to write a biography that combines the life story with an in-depth analysis of the work to bring out the deeper dynamics that drive Leonard’s life,” Lebold told me. “The cosmopolitan impulse that takes him from city to city and tradition to tradition; the pursuit of love in all its forms; the battle against depression; the spiritual quest and a game of hide-and-seek with God. I also believe this is the first ‘big’ biography that puts Zen Buddhism in its rightful place in Cohen’s life. Leonard frequented monasteries for over forty years, and his intimate knowledge of Zen life was a determining factor in his quest for lightness and the development of the figure of the (sometimes ironic) spiritual master that he embodied so well at the end of his life.”

Lebold does not shy away from direct discussion of Cohen’s controversial Zen teacher, Joshu Sasaki Roshi, who was found by a sangha investigation to have preyed sexually on dozens of women or more. Lebold straightforwardly acknowledges both Sasaki’s behavior and Cohen’s intense devotion to him. As far as Cohen’s relationship with Sasaki, I share Lebold’s opinion that Cohen didn’t see himself as the judge of people in his life. In the end, he neither had illusions about Sasaki’s abusive behavior nor did it stop him from loving his longtime friend, by whose deathbed he sat vigil years after the allegations had become public.

One of the refreshing things about Lebold’s book is how he integrates Zen into his writing. One of many examples is in his description of Cohen’s childhood dogs, a white fox terrier called Kelef and his successor, Tinkie. Lebold writes of an early photograph of Cohen:

It is summer; the day seems very hot, and the dog is exactly the same size as the future poet. They are friends and you can tell—preparing for a life where he will be photographed a lot, Leonard looks straight at the lens while the dog looks at the ball laid in front of his little master. He seems to be pondering the famous question asked by a monk to Master Zhaozhou in a thirteenth-century book of koans known as The Gateless Gate: “Does a dog have Buddha-nature?”

Kelef is soon replaced by Tomavitch, a.k.a. Tinkie, another fox terrier—a black one this time—who will follow his young master to school every day and sleep under his bed every night for fifteen years. No doubt the animal felt that Leonard’s heroic life could begin at any moment and that constant watching over was therefore required. He was the four-legged La Boétie of the little Jewish Montaigne of Westmount: together they discovered the power of elective affinities and the eloquence of shared silence. Cohen has spoken at length about this dog’s death in the early 1950s, a moment he has always presented as a lesson in dignity and compassion. One winter evening, the poor sick animal went out and died under the piles of the house next door to reappear only when the snow had melted the following spring, as everyone, including his young master (who was away from town), was ready for the unacceptable. So, does a dog have Buddha-nature? In The Gateless Gate, Master Zhaozhou’s answer is “Mu!”—a great negation which literally means “no” in Japanese, but which, in fact, dissolves the question and transforms the Buddha, who utters it into a barking dog that goes “Mu! Mu! Mu!” It is a “no” that means “yes” and that transcends dualist thinking. In any case, twenty-five years before he met Sasaki Roshi, Leonard took his first Zen lesson as he left childhood—a lesson given by a dog: know how to disappear with grace. Later, the poet would greatly admire Saint Francis of Assisi for preaching to birds, and when singer Rufus Wainwright first met him, Leonard was in his underpants, feeding a wounded bird. The lessons in compassion had been well learnt.

Although I thoroughly enjoyed Lebold’s book, I regularly differed from his interpretations of Cohen’s art, motivations, and perspectives. I suspect any other Cohenophiles may find the same—perhaps in different places—yet Lebold’s book has so much else to offer that I soon forgot about this, lost in the rich world of literary and biographical analysis, which very few could do as well as Lebold has done.

![]()

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.

Kass

Kass