Hot Docs 2022 Women Directors: Meet Noura Kevorkian – “Batata”

Noura Kevorkian is a Syrian-Lebanese filmmaker who made her filmmaking debut with her first short documentary ” Veils Uncovered” (Official Competition, Amsterdam IDFA) about lingerie and the veiled women of Damascus. Kevorkian’s second film, “Anjar: Flowers, Goats and Heroes,”...

Noura Kevorkian is a Syrian-Lebanese filmmaker who made her filmmaking debut with her first short documentary ” Veils Uncovered” (Official Competition, Amsterdam IDFA) about lingerie and the veiled women of Damascus. Kevorkian’s second film, “Anjar: Flowers, Goats and Heroes,” is a historical POV documentary about a young girl growing up during the Lebanese Civil War who discovers that all the elders of her village are genocide survivors from World War I. Kevorkian’s first feature film, “23 Kilometres,” is the experiential story of a man living with Parkinson’s disease.

“Batata” is screening at the 2022 Hot Docs Canadian International Film Festival, which is taking place April 28-May 8. Find more information on the fest’s website.

W&H: Describe the film for us in your own words.

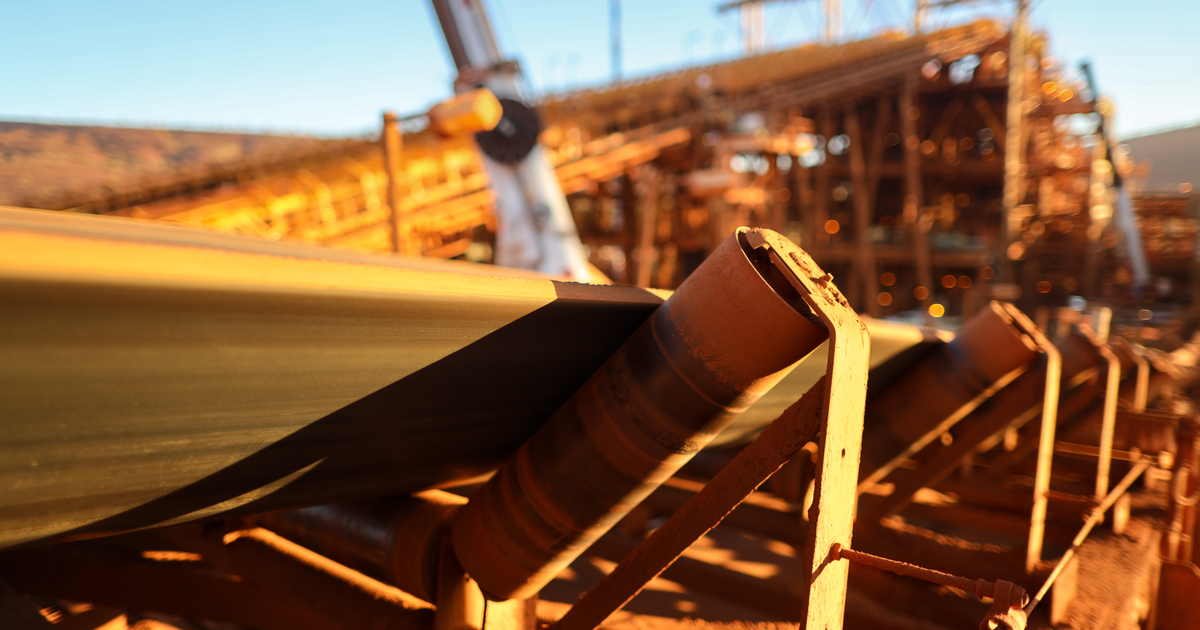

NK: “Batata” started in 2009 as a story about a Syrian farmer: a woman named Maria who worked for Mousa, a Lebanese landowner. Set in beautiful green potato fields in Lebanon’s Bekka valley where I grew up, the film was to address the tense relationship between Lebanon and Syria.

The film took a different turn that none of us were prepared for when, in the middle of filming, the Syrian revolution broke out. The story became much larger, providing an insider’s look into the lives of refugees over an unprecedented 10-year period.

Starting in 2012 with the beginning of the Syrian Refugee Crisis, the beautiful potato fields started slowly to transform. With Maria’s family and relatives from Raqqa Syria escaping the war and arriving in huge numbers, Maria and Mousa’s migrant-worker camp offered a safe haven. Over the years, as millions more fled the escalating war in Syria, the Bekka’s green fields were taken over by sprawling refugee camps with thousands of tents.

The film shows the devastation of war and its impact on displaced people. In the current global context, I believe “Batata” offers a perspective and maybe even some foresight into what is unfolding today, exactly 10 years later, in Eastern Europe – a tragic repetition of events.

W&H: What drew you to this story?

NK: Originally, my intention was to make a film about the historical tension between Syria and Lebanon. These two countries are part of my own family’s history. My mother is Syrian, and my father is Lebanese. I was born in Syria yet grew up in Lebanon. All my life, I felt a love/hate relationship between these two Arab neighbors and wanted to find a non-political way to tell the story.

One day in 2008, while visiting my parents in Lebanon’s Bekka Valley, my mother’s friend Mousa invited me to take a ride in his famous red Chevrolet pickup truck. It was there in the green fields I first saw Maria walking towards me in her stunning red dress.

That day I knew I had found my story. Here was a striking and charismatic Muslim Syrian itinerant farmer woman working for a Christian Lebanese landowner man. It was the perfect cast of subjects I had been looking for to launch into the story of two nations that I had long wanted to tell.

The following year, in 2009, I started shooting “Batata” – “potato” in Arabic — thinking I would complete filming by the fall harvest of 2011. However, in March of 2011, the Syrian revolution started and everything changed. Maria and her family quickly went from farmers to refugees, and I couldn’t stop filming, hoping to capture an end to the hostilities and to see Maria return home to Syria.

Thirteen years after I first started filming, the film is finally complete and is touring international festivals, bringing the world Maria’s story, representing the experiences of over six million Syrian refugees similarly displaced in what remains the world’s largest human forced migration crisis of our times.

Tragically it is not the last refugee crisis as Ukrainians now stream across borders seeking safety from a new senseless war.

W&H: What do you want people to think about after they watch the film?

NK: “Batata” is unlike any other refugee documentary to date. The film gives audiences a unique opportunity to witness, from a woman’s perspective, an entire decade in the lives of refugees, representing the millions of nameless and faceless Syrians lost and all-but-forgotten outside their homeland.

As a verité film, “Batata” offers a very intimate access inside the tents and lives of these refugees living in extremely harsh conditions.

2022 marks the 10th anniversary of the Syrian Refugee Crisis and yet Maria and six million other Syrians still remain displaced, unable to safely return home. Sadly, war and forced migration appears to be increasingly commonplace: a year prior to the Ukraine, Armenians were displaced en masse during the Artzak war, and prior to them the Afghanis.

I would like people to see the film and to keep helping refugees if they can. Donations to UNHCR and similar NGOs do help. Every refugee needs our support.

W&H: What was the biggest challenge in making the film?

NK: I originally set out to make one film, but war turned my story into something else entirely. I was definitely not prepared to face the emotional and psychological challenges of filming such a devastating crisis from the inside, covering real people’s lives and their incredible losses for an entire decade. It took a huge toll on me both as a woman and as a filmmaker.

Years of accumulated conflict, trauma, and violence built up over 10 years. Although I was behind the lens filming, I was also living alongside them for so long, experiencing it all as it happened — it was impossible to find the right balance between being a filmmaker and being a compassionate human being. Ultimately there was an emotional and psychological toll that I was not prepared to deal with when I first set out to shoot the film.

W&H: How did you get your film funded? Share some insights into how you got the film made.

NK: Like many independent documentary filmmakers, when I first began shooting “Batata,” I used my own money. In 2012 we pitched the project at the former Dubai International Film Festival, winning the best pitch award and a prize of USD $25,000. Later we received grants from Canada Council for the Arts, Ontario Arts Council, and the Doha Film Institute.

While the funds raised would have been ample for the original film, the budget was nowhere near enough to cover the 10 years of filming and two years of editing. While I was a one-woman crew – director, camera operator, and sound recordist all in one – only having to cover my own costs.

Thankfully, I was able to complete another film in far less time (“23 Kilometres”), which helped pay the rent. My commitment and determination are what made this film, along with the sacrifices my children and husband put up with throughout the whole process.

A family project of love and humanity is what I call it.

W&H: What inspired you to become a filmmaker?

NK: I was a young girl in the 1980s, growing up during the Lebanese Civil war with hardly any electricity which meant almost no access to television. In my house, the TV set was used as a plant stand – never to be turned on. So, I lived mostly in my own imagination.

It also helped that my mother is a great storyteller. In fact, the entire village where I spent my childhood was full of storytelling elders. From a young age, I collected stories and imagined them visually in my head. I love opera, and so I conjured up stories and imagery choreographed to music in my head for years.

While we had no TV, my father did love movies, so once a month – when the roads were open and safe – he would drive my sisters and I down the Biblical Damascus highway in Lebanon to the nearest city with a movie theater. My love for film only grew from there.

Kids living in war don’t get many chances in life. This is why I came to Canada as a young woman to follow my dreams.

W&H: What’s the best and worst advice you’ve received?

NK: My first year in Canada, my high school counselor advised me not to study film in university so I wouldn’t become a “starving artist.” With the best of intentions, he explained that as a young girl on my own, with no family in Canada, I would have to be self-reliant, and earn a living with a solid job. That was both the best and the worst advice.

I ended up studying economics and finance at the University of Toronto. However, life and passion eventually brought me back to the career my high school counselor tried to protect me from. Sometimes we can’t change our fate.

W&H: What advice do you have for other women directors?

NK: As a woman director, I would advise others before embarking on any project that involves violence, trauma, or war to prepare for the worst, and have a solid support system in place from the outset. Directing is an extremely difficult job already, but when you add topics like hatred, sexual assault, and murder, it becomes all-consuming, even detrimental, to your emotional, mental, and ultimately physical well-being.

Regardless of who they are, every director needs to be prepared to deal with difficult subject matter. Women working in remote and dangerous situations need to be doubly prepared. So, get help before you start your project. Consult professionals. Agree and commit to what lines you don’t want crossed, and know when it is ok to stop the project and shut it down. Don’t burn out from taking on too much. Your well-being is more important than any film.

Personally, I learned these lessons too late. But I’m hoping people will learn from my own experiences and do things differently.

W&H: Name your favorite woman-directed film and why.

NK: That’s tough. Many of my favorite directors are women, including Agnieszka Holland, Jane Campion, Chloé Zhao, and Canadian filmmaker Jennifer Baichwal. If I were to examine why, one reason is that they make films that compete with the very best films out there, yet aren’t initially obvious that they were made by a woman. It’s only upon deeper reflection that one realizes these films could only be made by a woman. As for my favorite recent film, I’d have to say it’s Zhao’s “Nomadland.”

W&H: How are you adjusting to life during the COVID-19 pandemic? Are you keeping creative, and if so, how?

NK: The pandemic was extremely difficult for me. I was forced to cancel my travel plans to Lebanon. I was isolated at home with my two young kids, my husband, and our new adopted dog – a refugee himself, rescued from the streets of Cairo. With the kids at home crammed into our small house, I had to face the hundreds of hours of footage shot over 10 years to try to piece “Batata” into a cohesive story.

It was a daunting job – the hardest of my career. I was already suffering from depression and PTSD, so it was like “squeezing lemon juice on an open wound” as the Armenians say. Thankfully, we brought in an editor, Mike Munn, to help me cut my four-hour rough cut down to its current length. That was a huge help as I was unable to let go of even one frame of footage! I was that attached to my story and subjects.

W&H: The film industry has a long history of under representing people of color on screen and behind the scenes and reinforcing — and creating — negative stereotypes. What actions do you think need to be taken to make Hollywood and/or the doc world more inclusive?

NK: I’m very impressed with the steps taken recently within the film industry to finally make room for authentic, diverse voices. Creators and performers of varied racial, cultural, and sexual identities now have opportunities formerly denied to them through systemic barriers.

I’m glad to witness this change during my own career. I hope the progress continues, reaching a stage that would make the topic obsolete, rectifying and recalibrating 100 years of a discriminatory history within the entertainment industry.

Fransebas

Fransebas