I asked AMD about the future of graphics, and I was shocked by the response

AMD says that AI will "dream up" parts of your PC games in the future. I asked the company how we get there and what that looks like.

Jacob Roach / Digital Trends

Jacob Roach / Digital TrendsLast week, I was in Los Angeles at AMD’s Ryzen 9000 Tech Day, digging into the Zen 5 architecture and AMD’s upcoming CPUs. But out of everything I heard about architecture, an offhand comment about how AI will “dream up” future PC games stood out to me the most.

The comment came from Sebastien Nussbaum, the computing and graphics chief architect for AMD. Nussbaum was laying out a vision of AI in the future, and among talks of AI assistants and features like Windows Recall, he talked about how AI could “dream up” the lighting in PC games in future. The obvious next question: how?

Sure, we’ve seen some applications of AI in games, from Nvidia’s DLSS to features like G-Assist and AI characters through ACE. But AI just imagining lighting in games? That sounds like a stretch. I sat down with Chris Hall, senior director of software development at AMD, to understand the winding road leading to an AI future of PC games. As it turns out, it sounds like we’re a lot further down that road than I thought we were.

The vision

OpenAI

OpenAI“I think you need to look at a technology like Sora,” Hall started when I sat down to speak with him. “Sora wasn’t even trained to think about 3D. They call it a latent capability… it somehow developed a model of what a 3D world looks like. Naturally, you look at that and say, ‘surely that’s what a game is going to be like in the future.'”

Hall is referring to OpenAI’s video generator, called Sora. It can create video from a text prompt, and with elements like proper occlusion of objects (where one object passes in front of another). It’s not a video game, not even close. But when you look at what something like Sora can do, with its ability to understand and interpret a 3D world, it’s not hard to let your imagination run wild.

“[AI] requires a completely different mindset”

We’re not even close to something like Sora for games today, which is something Hall was upfront about. But the software developer says that AMD — and I’m sure the rest of the gaming industry — is researching the technologies that could eventually lead to that point. It won’t come easily, though.

“This is a huge change for the game industry,” Hall said. “This requires a completely different mindset.” Hall spoke about upending the traditional graphics pipeline we know today, something that requires years of research and work to accomplish. According to him, however, that shift has already started.

“You can see some of these foundational pieces are already compatible, and there will be steps along the way,” Hall told me. “We already have denoising in games today, and if you think about Stable Diffusion-type technologies, the diffusion process itself is literally denoising an image toward a final outcome. So it’s almost like guided denoising.”

There’s a gradual shift that the gaming industry is going through. There may be a future where, years down the line, AI can work its way into every part of the graphics pipeline. That change, Hall said, won’t come with flashy generative AI features that we’ve seen through dozens of tech demos. It will show up in the mundane aspects of game development that players will probably never think of.

Loving the mundane

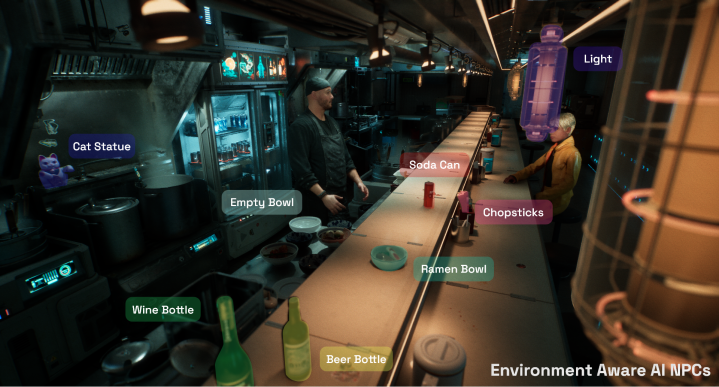

Epic Games

Epic GamesWe’ve seen applications of generative AI in games already. There’s Nvidia’s Project G-Assist most recently, as well as AI-driven NPCs through Convai. They grab headlines, but Hall said the real innovation right now is happening in the mundane.

“AI has got all the headlines for the fancy things — the LLMs, the Stable Diffusions, right? A lot of people today think that’s all AI is. But if you look at Epic Games and the Unreal Engine, they were showing off their ML [machine learning] cloth simulation technology just a couple of months ago,” Hall said. “Seems like a very mundane, uninteresting use case, but you’re really saving a lot of compute by using a machine learning model.”

Hall is referring to Unreal’s Neural Network Engine (NNE), which moved into a beta stage in April with the release of Unreal Engine 5.4. It provides an interface for developers to run neural network models in a variety of places in games — Epic Games provides tooling, animation, rendering, and physics as possible examples. Instead of generating a game with AI, the application here is to make more impressive visuals more efficiently.

“That’s a case where using machine learning to do something that requires a lot of compute traditionally frees up a lot of GPU cycles for what the game companies really care about, which is incredible visuals,” Hall said.

Jacob Roach / Digital Trends

Jacob Roach / Digital TrendsWe can already see that in action today in games like Alan Wake 2. The game supports Nvidia’s Ray Reconstruction, which is an AI-powered denoiser. Denoising is already a shortcut for rendering demanding scenes in real time, and Ray Reconstruction is using AI to provide better results at real-time speeds. Hall suggested that similar applications of AI in game development is what will push a new level of visual quality.

“You’re going to see a lot of those things. Like, ‘oh, we can use it for this physics simulation, we can use it for that simulation,'” Hall said.

The problem right now is how to get the resources to run these models. NNE is a great framework, but it’s only set up to work on the CPU or GPU. And Nvidia’s DLSS features are excellent, but they require a recent, expensive Nvidia GPU with dedicated Tensor cores. At the moment, there are duct tape solutions for getting these features working while companies like AMD, Nvidia, and Intel lay the hardware foundation to more efficiently support these features.

Jacob Roach / Digital Trends

Jacob Roach / Digital TrendsAnd they are laying that foundation, make no mistake. We have Tensor cores in Nvidia GPUs, of course, and Intel has its XMX cores in its graphics cards. AMD has AI accelerators inside RDNA 3 GPUs like the RX 7800 XT, as well, which don’t have a clear use at this point. There’s a classic chicken-and-egg problem with AI acceleration in games right now, but AMD, Nvidia, and Intel are all working to solve that problem it seems.

“If I add this AI feature in, am I blocking a whole set of generations of hardware that can’t support this feature? And how do I fall back on those? These are the things that seem to be making the incorporation of ML a slower process,” Hall told me.

Still, the process is happening. Recently, for example, AMD introduced neural texture compression, and both Intel and Nvidia submitted similar research last year. “It’s not flashy, it’s not a central feature of the game, but it’s a use of ML that’s otherwise hard to do analytically, and the improvement for the user is the loading time and the amount of data you need to deliver to the user’s PC,” Hall said. “So, I think you’ll see more of those.”

Something that solves problems

Sony

SonyWhen you hear things like AI dreaming up aspects of a game, it all starts to feel a little dystopian. If you keep up with the tech news, it’s easy to feel like companies are shoving AI into everything they possibly can — and with a box that claims to let you smell video games through AI, it’s hard not to get that picture. Hall’s view of AI in PC games is more grounded. It’s not about shoving AI in places it doesn’t belong. It’s about solving problems.

“AAA and even AA game development is not a six-month process. It’s planned out a long time in advance. You’re always trying to bite off more than you can chew, so you’re always under the gun on schedule. Adding a new, extra complex thing on top, it really needs to solve a problem that exists,” Hall told me.

“It will take some deep pockets on the part of game publishers.”

Game development is not only a long process but also an expensive one. It can cost hundreds of millions of dollars to produce a AAA game, and even with companies like Square Enix haphazardly putting AI in a game demo, there isn’t a game developer dropping that kind of a money on a feature that could ruin a game. We’ve also seen companies like Ubisoft demo the capabilities of AI NPCs in games, but those haven’t shown up in an actual game. And they likely won’t for quite some time.

“I think the reality of [AI NPCs] is that… you know, games are very carefully scripted experiences, and when you have an essentially unbounded experience with this character in the game, you’ve got to put a lot of effort into making sure that doesn’t break the scripted elements of your game,” Hall said. “So NPCs are nice to have, but it’s not going to change how many games sell. Whereas a new graphics feature where you’ve offloaded more from the GPU… well, that’s interesting.”

Convai

ConvaiI have no delusions about the reality of game development. Large companies spending hundreds of millions of dollars will find a way to shortcut that process by reducing the headcount and relying on AI to pick up the slack. I just don’t suspect it will work. There’s a lot of potential for AI in PC games, but that potential comes from achieving the next major leap in visual quality, not reducing the experiences we love to something a machine can understand.

“It will take some deep pockets on the part of game publishers and some brave souls to make that leap, but it’s inevitable because this technology is inevitable,” Hall said.

Pushing graphics forward

Jacob Roach / Digital Trends

Jacob Roach / Digital TrendsAI sets up an interesting dynamic when it comes to creation. It either allows companies to do the same work with less people, or it allows them to do more work with the same amount of people. The hope is that AI can push PC gaming forward. That next big leap is what companies like AMD are looking toward, Hall said.

“We were all enjoying Moore’s Law for a long time, but that’s sort of tailed off. And now, every square millimeter of silicon is very expensive, and we can’t afford to keep doubling,” Hall told me. “We can, we can build those chips, we know how to build them, but they become more expensive. Whereas ML is kind of breaking that cost per effect by allowing us to use approximate computing to deliver a result that would otherwise take something perhaps four or five times more powerful.”

“It’s truly a research project. It’s just that we know now that it will be possible.”

I was caught up on the idea of AI dreaming up the lighting in my games. It felt wrong, like another case of shoehorned AI in an experience that’s supposed to be crafted by a person. My conversation with Hall brought a different perspective. The idea of pushing the medium forward is exciting, and a tool like AI allows the industry to get a major leap without resorting to GPUs that cost thousands of dollars and consume thousands of watts of power.

Hall summed up the process nicely by looking back. “There will be a before and an after, and I suppose it will be similar to the early days of 3D. Remember when Nintendo shipped the [Super Nintendo] Star Fox cartridge with a little mini triangle rasterizer in it so that it could do 3D? They had to add some silicon to their existing console to deliver a new experience.”

Nintendo

NintendoEspecially as someone who covers the tech industry every day, I find myself getting cynical about the tech. Like any powerful technology, there are plenty of negative implications of AI. It doesn’t sound like that’s the work going on behind the scenes right now, though. It sounds like small, localized applications to provide a better experience for players and (hopefully) developers, as well. And, over time, maybe AI can dream up something special. It won’t be free, though.

“What gets us from here to that endpoint? Honestly, it’s a lot of trial and error and a lot of hard work. It’s truly a research project. It’s just that we know now that it will be possible,” Hall said.

JaneWalter

JaneWalter