‘Is There a Woman Buddha?’

Faced with a question from her niece, a Buddhist practitioner reckons with the legacies of patriarchy within the tradition. The post ‘Is There a Woman Buddha?’ appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

“Do elephants live in water? Can I have an iPad for my birthday? Is there a woman Buddha?” Imagine a six-year-old with sparkling brown eyes, her youthful curiosity contagious, showering you with questions that can light up a lazy Sunday. Say xin chào to my niece, Aurora.

One afternoon, we were curled up in my personal haven in Olympia, reading a children’s book called Grace for President. This book is about a young Black girl named Grace who’s surprised to learn that no woman has ever occupied the Oval Office in the White House. This discovery lit a fire in her to challenge societal norms. So she decides to run for president in her school’s mock election.

With the painting of the Buddha’s serene presence filling the room, Aurora and I traced Grace’s journey through her presidential race, page by page. The climax of the story, where Grace emerges victorious by a single vote against a boy who declared himself the “best man for the job,” ignited a spark in Aurora. If a girl can win a school election, why not a US presidential one? Are some roles only for men?

Her eyes, reflecting a mixture of curiosity and wonder, drifted from the Buddha painting that loomed behind me to rest on my face.

“Auntie Nhi, is there a woman Buddha?” she asked, a budding lotus in her earnest gaze.

A warm flush spread across my cheeks as I grappled with the gravity of her inquiry. In that moment, I knew that my response had the power to uplift or confine her young, hopeful spirit. I wanted to answer her honestly yet reassuringly, to both nourish and foster her blooming self-confidence.

But here’s the thing. A passage in the foundational text of Theravada Buddhism, the Pali Canon, declares that only a man can become a buddha. Meanwhile, the Lotus Sutra, a revered text in Mahayana Buddhism, presents an alternative view. It shares the story of Śāriputra, a chief disciple of the Buddha, who doubts a dragon princess’s ability to attain buddhahood, saying, “This is difficult to believe. Why? The body of a woman is filthy and not a vessel for the dharma.”

But the dragon princess isn’t discouraged. Offering a precious pearl to the Buddha, she announces, “Watch as I become a Buddha!”

Then, in a swift whirlwind of transformation, she turns into a man, ventures to “the world without filth,” and shortly thereafter achieves buddhahood.

Many Mahayana Buddhists interpret this story as evidence that women can indeed become buddhas. But there’s an implicit suggestion in the story, isn’t there? Sure, women can become buddhas, but only if they first assume a male form. This narrative perpetuates the notion that being female is a lesser state, an inadequate condition for enlightenment.

Such biases, particularly the belief that a woman’s body is inherently filthy, never fail to irk me. It’s a misconception found in many cultures that not only strips women of their dignity but also reinforces patriarchal structures that continue to hinder gender equality. This discrimination manifests in a number of ways, including barring menstruating women from spiritual practices and community participation and perpetuating harmful taboos.

But I couldn’t dive into all of this with Aurora just yet. Nor could I confess that the female deity of my childhood wasn’t, in fact, female at all.

So I steered toward empowering narratives. “Yes, Aurora! There are many women buddhas. The most famous is the bodhisattva of compassion, or Bồ Tát Quan Âm in Vietnamese.”

Aurora’s eyes widened as she asked to see pictures. Her four-year-old sister, Aria, who had been engrossed in an iPad game, chimed in. “I want to see pictures too!”

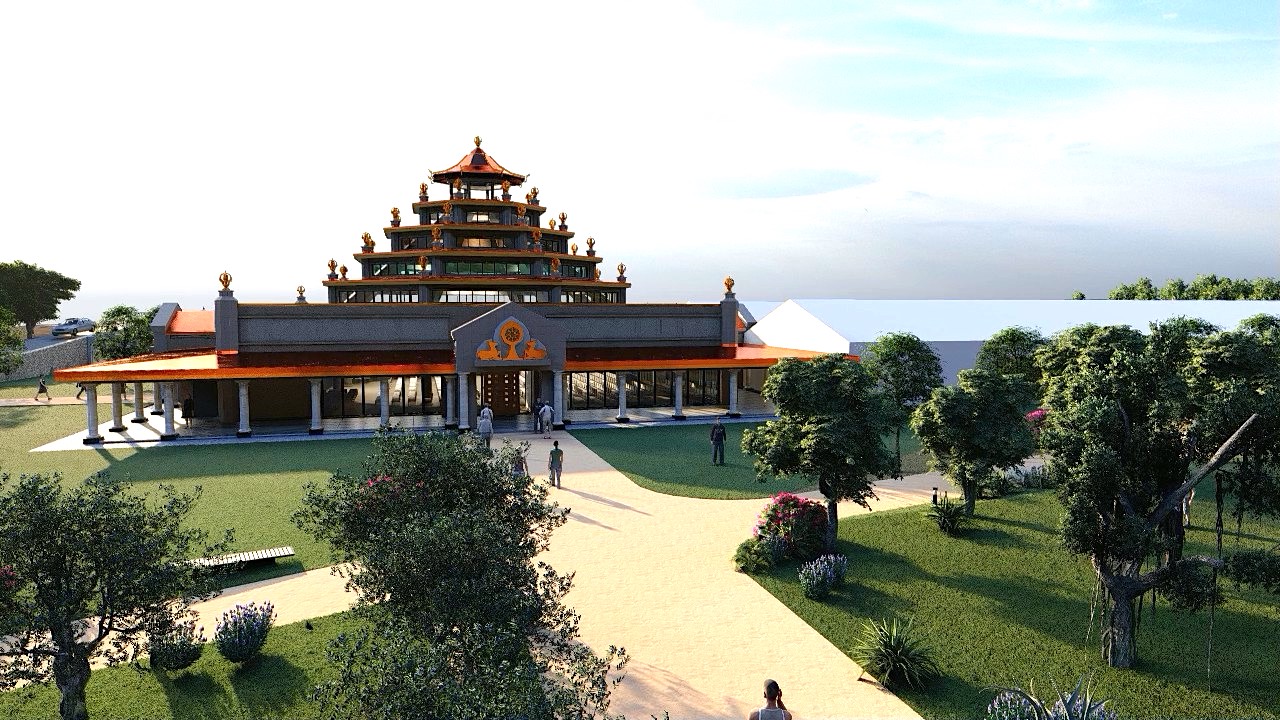

After showing them dozens of images of Quan Âm and answering their many questions about her various forms, I led them downstairs to my parents’ dining room. There, I pointed to a wooden shrine housing four statues of Quan Âm, photos of my late grandparents, several orchid plants, and fruit offerings around a lotus-engraved incense bowl.

“See,” I motioned toward the top shelf, “those are all Quan Âm.”

“All of them?” Aurora said, awestruck.

“Yes.”

Aria, eager for a closer look, asked to be lifted. As she observed the statues, her eyes shimmered like starlight. Pointing at a Quan Âm image on an incense box, she said, “Is that her too?”

“Yes. She’s so loved that she’s everywhere.”

At that moment, Aria’s smile unfolded like a rainbow after a rain, brightening the room.

Feeling a twinge of guilt for my little fib, I watched my nieces in quiet admiration. I knew this moment would become a precious memory for them. Out of all the divine figures in the world, my parents chose to honor Quan Âm, a female bodhisattva and future buddha, a deity reflecting their own image.

But as they would inevitably grow older, they would encounter the same societal challenges and gender inequalities I faced in my youth. They’d grapple with the double standards applied to men and women and uncover the not-so-pleasant truth about Quan Âm’s gender evolution. I knew their young hearts would be filled with disappointment, their world slightly darkened by the revelation. But, by that time, I hope that the girls will have the confidence they need to navigate these hidden pitfalls. Right now, as young girls with bright futures, they need to understand that their potential—and the potential of every girl and woman—was limitless. This eternal truth surpasses the constraints of any patriarchal faith.

Quan Âm was more than a mere divine figure in my life. Growing up in Vietnam, I had always associated her with compassion, protection, and progress—a symbol of solace for men and affirmation for women, a soothing presence for those in fear or pain.

When Typhoon Noru devastated Vietnam in 2022, several of my friends reached out to her on social media, asking for her protective grace. Two of my sisters keep amulets of Quan Âm in their cars for the same reason. One of them also has two statues of Quan Âm in her home’s shrine, with the Buddha nowhere in sight.

This reverence for Quan Âm isn’t exclusive to my family. Almost every Vietnamese Buddhist I’ve met holds her in high esteem. In fact, it wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that given the choice to honor a single deity at home, many would choose Quan Âm over the Buddha himself.

Vietnam is a nation shaped by a tumultuous past, tasting the bitterness of enslavement, colonization, and external domination for over a thousand years. Its short fifty years of independence are but a blink of an eye compared to the long and gloomy ages preceding it. Our collective experience has been one of hardship and struggle, which is why Quan Âm’s promises of compassion and relief resonate more deeply than the Buddha’s path of self-enlightenment. It’s not that one is superior to the other. It’s just that our historical scars draw us closer to the deity who offers a balm for our wounds.

But in my twenties, I came across a startling revelation: Quan Âm wasn’t always a woman. She’s a Vietnamese adaptation of Guānyīn, a female bodhisattva from China, who herself evolved from Avalokiteśvara, a bodhisattva of compassion initially depicted as a man in early Buddhist art of India.

Around the twelfth century, the Chinese transformed Avalokiteśvara into Guānyīn. And when Mahayana Buddhism made its way to Vietnam, Korea, and Japan, Avalokiteśvara was mainly depicted as a woman, as the Goddess of Mercy.

In other words, Guānyīn and Quan Âm are versions of the same figure—born from Buddhist creativity and Chinese scriptures from the Six Dynasties period.

They are, in essence, not real.

My initial reaction to this discovery was a mix of emotions—disbelief, annoyance, a touch of anger. I wanted to brush it aside as a mere speculation. But, deep within me, I knew that society frequently asks women to bloom while planting them in the shade. In the Mahayana Buddhism that my family practices, all buddhas and bodhisattvas were men, except for Quan Âm. And now even she wasn’t originally ours.

The real sting, however, wasn’t just the discovery of an imaginary deity. It was the persistent sense of being considered less than men in matters of spirituality. Losing a sacred symbol felt like a paper cut compared to the soul-crushing reality of misogynistic teachings presented as the Buddha’s words.

It’s painful for women like me who yearn to follow in the Buddha’s footsteps, only to be told that we are barred from enlightenment, are burdened by bad karma, and are the cause of the decline of Buddhism. How could we persist in a path we cherish when our efforts were considered fruitless, and our very presence accelerated its downfall? This harsh reality is the shared plight of women Buddhists worldwide.

Yet, like a bird breaking free from a cage, truth always finds a way to unfurl its wings.

The Buddha is said to have declared, “Three things cannot be long hidden: the sun, the moon, and the truth.” This quote originates from a passage in the Pali Canon that states three things shine openly for all to see, not hidden: the moon, the sun, and the Buddha’s teachings.

The Buddha, in his radiant enlightenment and benevolence, not only welcomed everyone onto the path but also proclaimed that each of us—irrespective of gender, class, or background—holds the innate potential for enlightenment.

For Buddhists, the Buddha’s teachings and the truth are two peas in a pod. They are one and the same. But after the Buddha’s passing, the task of interpreting these teachings fell solely to the monks. As is often the case when knowledge passes through various lenses, the narrative began to shift. Women were gradually cast as lesser beings. They were painted with broad strokes, seen as prone to desire, seductive, and distracting. Their emotional complexity was viewed as instability, and their natural biological processes were misconstrued as impurity. This fostered a misguided perception that women were inherently incapable of achieving enlightenment.

These distorted views reinforced male dominance in religious circles and led to the marginalization of women within Buddhism. The most devastating impact was the pervasive sense of inferiority that seeped into the minds of women worldwide, igniting a cycle of internalized oppression that continues to echo across generations.

But as the Buddha reminds us, his teachings shine openly, like the sun’s radiant glow, illuminating all without exclusion. In our modern age, we don’t have to depend on monks anymore for access to the dharma. With a simple click, the scriptures are at our fingertips. Buried within these texts lies a beacon of hope—an empowering counternarrative to any discrimination imposed on women by the Buddha himself.

For the past twenty-five hundred years, what has obscured this light were human limitations and biases that twisted his teachings. The Buddha, in his radiant enlightenment and benevolence, not only welcomed everyone onto the path but also proclaimed that each of us—irrespective of gender, class, or background—holds the innate potential for enlightenment.

The truth is out there, waiting to be discovered. But it’s up to us to sift through the noise, question the status quo, and turn the page to unveil what lies beneath the ink of tradition.

♦

From Budding Lotus in the West: Buddhism from an Immigrant’s Feminist Perspective by Nhi Yến Đỗ Trần, copyright © 2024 Broadleaf Books. Reproduced by permission.

JimMin

JimMin

.jpg&h=630&w=1200&q=100&v=6e07dc5773&c=1)