It’s time to start authenticating educated wellness influencers

Social media platforms have introduced policies to tackle Covid misinformation, but what about other health information? There’s zero fact-checking when it comes to the credentials of some wellness influencers, and clinical nutritionist Lexi Crouch wants to change that.

Social media platforms have introduced policies to tackle Covid misinformation, but what about other health information? There’s zero fact-checking when it comes to the credentials of some wellness influencers, and clinical nutritionist Lexi Crouch wants to change that.

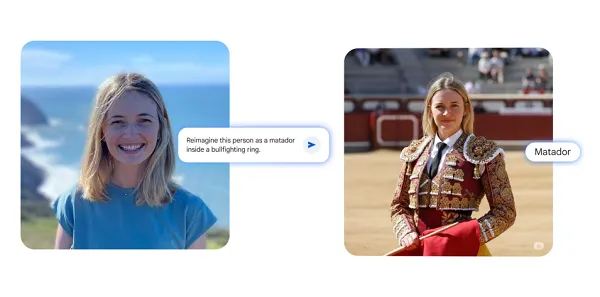

When you see a blue tick next to a person’s name on Instagram or Twitter, you can feel confident that person is who they say they are. But what if we could do the same for wellness influencers to authenticate their education and guarantee the information they’re posting is reputable and based on science?

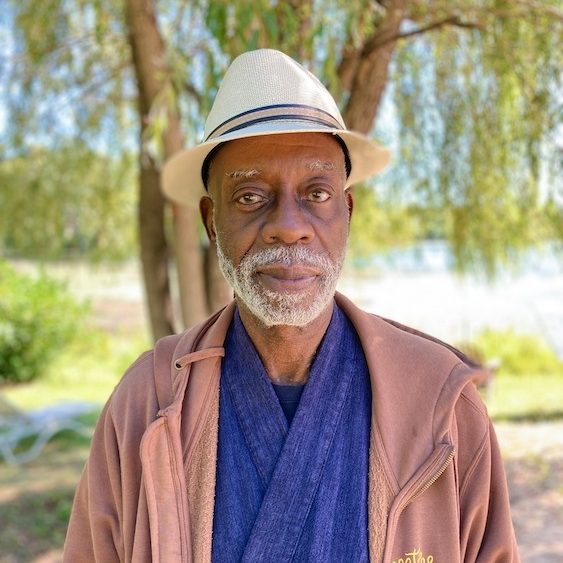

Lexi Crouch, a clinical nutritionist and eating disorder advocate who spent three years of academic study to inform her approach to wellness, sees enough dietary misinformation and warped portrayals of reality to think this is a good idea.

“Being an influencer, we are now not allowed to post anything unless without disclosing we're doing a collaboration or it is a paid sponsorship,” she says.

Like what you see? Sign up to our bodyandsoul.com.au newsletter for more stories like this.

“I feel that that should be done with health advice as well and that will give people the option to think themselves.”

Our conversation comes after a report from Endeavour College of Natural Health that found almost half of young adults, aged 18-24, follow influencers with no knowledge of their qualifications, if they have any. Frankly, it’s unsurprising, but still a cause for concern.

“There are too many incidences of so-called experts making inaccurate health claims. Not only can this be harmful, but it’s also unethical and irresponsible,” says Endeavour College nutrition trainer Sophie Scott.

“Just as we expect to see accreditation when we enter a health practice, we’re calling on all health influencers to be clear about their qualifications so their audience can decide how credible they are.”

While social media platforms have made some effort to curtail Covid-19 and vaccine conspiracy theories, little if nothing is being done about diet and nutrition advice. It’s potentially just as dangerous, particularly for young girls who are highly influenced by toxic trends like #MyDayOnAPlate.

Crouch, who often works with teenagers suffering from eating disorders and having recovered from her own struggles, knows how damaging it can be.

“From my own 20-year battle with anorexia and the ongoing work I do with eating disorder organisations and sufferers, I've experienced and witnessed first-hand the devastating impact of irresponsible influencers,” she says.

“I wish more influencers would think before they post.”

The difficulty with social media and impressionable consumers is that it can be hard to differentiate ‘good’ from ‘bad’ advice. The disgraced Belle Gibson, who profited off the back of false claims ‘clean eating’ cured her of a cancer that she didn’t have, is an infamous example of this.

In the BBC documentary Bad Influencer, young woman Maxine described how, as a sufferer of ulcerative colitis, a chronic inflammatory disease of the large intestine, subscribed to Gibson’s ‘clean eating’ diet in the hopes of improving her quality of life.

She cut all supposedly toxic ingredients, like animal products, gluten, and carbohydrates, and became so underweight her health deteriorated, and she stopped having her period.

A solution to this blind spreading of bad information could be implementing a green tick of accreditation, similar to the verified blue tick we see on so many accounts already. It would allow consumers to quickly identify those with the necessary education to make scientifically-backed health claims.

“Instagram is in a position where it can make some safety moves,” she agrees.

“We’re seeing people that are getting sick because of bad information. I don’t want to use the word ‘control’, but that sort of stuff can and should be censored.”

So, the next time you read or see a wellness influencer’s post about their diet or wellness practices, question whether they have any formal education in what they’re talking about and remember that anecdotes are not real evidence: What works for one person may not work for you and it’s always better to reach out to a professional.

And if anyone claims green juice can “cleanse you of toxins”, it’s bullshit. (Your liver and kidneys do that already.)

Tfoso

Tfoso