Kosen Ohtsubo’s ‘Flower Planet’

The enfant terrible of ikebana speaks with Tricycle’s Mike Sheffield about free jazz music, Indian lingams, and the connection between flower arranging and the surrender of gassho. The post Kosen Ohtsubo’s ‘Flower Planet’ appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist...

Prologue: It all started at a birthday party in Chinatown. It is a quaint affair in an apartment close to the border of the Lower East Side. Music plays faintly while people chat in a small kitchenette and across a low arranged living room over bottles of sake and wine that are passed around with seemingly no end in sight. Piles of books line the walls from floor to ceiling: titles on art, politics, critical theory, philosophy, architecture, religion, music, mysticism.

The guest of honor’s best friend has flown in from the Bay Area and is making vegetable tempura to order in a big steel wok in the kitchen. Many hover around, grabbing crispy fried sweet potato, asparagus, and squash. The celebrant, Alex Lau, is a curator and senior director at Empty Gallery, a contemporary artspace in Hong Kong. In Spike Art Magazine, Stephen Cheng describes Empty as a place “where minimalist experimental music, Japanese conceptual art and its heirs, and sculptural and filmic practices at the forefront of the Asian diaspora converge in a renovated industrial space notorious for its dark, cavernous interior.” They also, sometimes, host raves.

Kosen Ohtsubo, Linga München, 2025, 300 Basket willow branches, candle, metal frame, plastic and metal ties, scrap metal, soil, various flowers and leaves, in: “Flower Planet,” Kunstverein München, Munich, 2024. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V. Photo: Maximilian Geuter.

Kosen Ohtsubo, Linga München, 2025, 300 Basket willow branches, candle, metal frame, plastic and metal ties, scrap metal, soil, various flowers and leaves, in: “Flower Planet,” Kunstverein München, Munich, 2024. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V. Photo: Maximilian Geuter.In the living room, when I tell Lau’s partner, Arias—a friend of mine from years earlier in Brooklyn—about my job at Tricycle, they show me some things they think I might be interested in. A book, Tibetan Buddhist Medicine and Psychiatry: The Diamond Healing. Pictures of trees decorated with Buddhist shamanistic elements that they came across at Haguro-san, one of the three mountains of Dewa Sanzan, a popular Japanese pilgrimage site and ancient province, holy to the Shinto religion and the mountain ascetic cult of Shugendo. And, finally, a few images associated with renegade ikebana artist Kosen Ohtsubo. Arias tells me that they were planning to host some of Kosen’s art at Empty Gallery, that Alex’s friend Christian had been the one to help make that connection. (Editor’s note: As of publication, this exhibition has yet to be realized.)

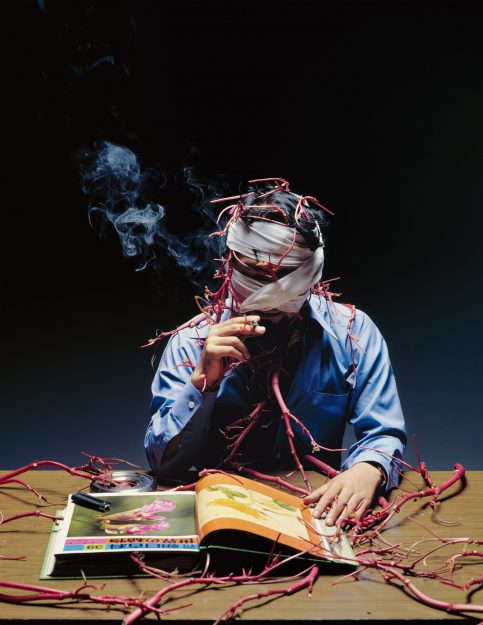

A few weeks later, I text Arias to follow up on our conversation. While on the surface level the least Buddhist of the threads that they had presented me with, an image of Kosen Ohtsubo’s sticks in my mind like a migraine. In one particular photograph (Kosen Ohtsubo, Botanical Man, 1978), the artist is present, his head wrapped in gauze, while he smokes a cigarette and reads a magazine (displaying his artwork); plant roots extending out of many different crevices, a plume of smoke drifting through the air. What does this have to do with ikebana, the traditional Japanese art of flower arranging? What does this have to do with Buddhism? And who is Kosen Ohtsubo? I ask Arias if they can make an introduction.

Kosen Ohtsubo, 植物人間 / Botanical Man, the artist, castor oil plant, produced in September 1978, first published in Ikebana Ryusei magazine, November, 1978. Photo: Ryusei photo department.

Kosen Ohtsubo, 植物人間 / Botanical Man, the artist, castor oil plant, produced in September 1978, first published in Ikebana Ryusei magazine, November, 1978. Photo: Ryusei photo department.While Arias is unsure of Kosen’s comfort level with English or with press in general, they seem more than confident that they could at least introduce me to Christian, who is a mentee of Kosen’s. “I think you and Christian would really click, actually. . . . I can’t articulate the web of connection in any way that makes sense right now, but it involves Venice, the music festival Dripping, and a candle made by monks.”

***

Christian Kōun Alborz Oldham is an artist and writer, born to an Iranian mother and Iowan father, in Woodland Hills, California, in the early ’90s, during the Rodney King riots. Christian incorporates temporary and permanent sculpture and installation, writing, publishing, video, still images, and music into their practice, which has included video and still image works for musical acts like Oneohtrix Point Never and Death Grips as well as design and archival work. In an unorthodox progression, Christian’s interests evolved from music to visual art and, eventually, to ikebana. And it would be in 2013, on a trip to Japan to learn more about the flower arranging practice, that Christian would first become aware of the work of Kosen Ohtsubo.

Christian Kōun Alborz Oldham, Penny Waking up from a Dream, 2025, carrot, Chinese long bean, reflecting sphere, Japanese woven bamboo basket, in: “Flower Planet,” Kunstverein München, Munich, 2024. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V. Photo: Maximilian Geuter.

Christian Kōun Alborz Oldham, Penny Waking up from a Dream, 2025, carrot, Chinese long bean, reflecting sphere, Japanese woven bamboo basket, in: “Flower Planet,” Kunstverein München, Munich, 2024. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V. Photo: Maximilian Geuter.Within a two-volume book on ikebana from the early 1990s, found in a used bookstore situated in a quiet suburb tucked away in Tokyo’s northwest Nerima district, Christian encountered a photograph titled Feeling High—Ikebana Bathing/I Am Taking a Bath Like This (1984). It was at this moment that Christian was first initiated into the explosiveness and charm of Kosen Ohtsubo. This precipitatory event was followed by years of correspondence and eventual training with Kosen in Japan in an intensive teacher-student relationship. In tandem with their training as an ikebana master and pupil, Christian began archiving the majority of Kosen’s extensive photo archive—found in a humidity-controlled cabinet in one of the storage areas of Kosen’s ziggurat-shaped house—from the last fifty years and giving lectures on the development and teaching of the practice. Beyond their mentor-mentee relationship, the two also began attending various ikebana exhibitions together, eventually becoming associated with each other in the area as somewhat of an “odd couple”—a famous Japanese octogenarian and his tall, well-dressed American protégé. In addition to continuing with Kosen’s ongoing “Flower Planet” studio, a project that involves creating as well as teaching ikebana, Christian is also beginning preparatory work on a publication chronicling the work of Kosen Ohtsubo and avant-garde ikebana at large. As part of this project, Christian has hosted lectures, workshops, and exhibitions of photographs of Kosen’s work in Seattle, New York, and Los Angeles, with upcoming events slated for Toronto.

Christian Kōun Alborz Oldham, Untitled, cable tie, metal cage, plastic tray, strelitzia, May 2012. Photo: the artist.

Christian Kōun Alborz Oldham, Untitled, cable tie, metal cage, plastic tray, strelitzia, May 2012. Photo: the artist.Christian’s physical ikebana practice and their work as the de facto archivist for Kosen have transformed their sense of artistic expression, as “these acts of mediation and concern for the visibility of Ohtsubo’s practice have become a medium for Christian to negotiate questions of collective authorship and appropriation, (il)legibility, and acts of advocacy,” according to an artist statement from their show at Kunstverein München. While indubitably unlikely, given the more than fifty years and half the world that served to separate the two, Kosen and Christian’s connection seems to be kismet, with the two being connected by their involvement with ikebana and the impermanence that is inscribed in both the botanical material itself and in their relationship as confidants. They both understand ikebana, as well as their own lives, as constant acts of negotiation, ones that involve an “almost-performative display of the illusion of control.”

I first message Christian over Instagram, saying that we should plan to connect over email. Over the course of a few email exchanges, it becomes evident that I am going to have to work closely alongside Keiko, Kosen’s daughter, in order for this interview to materialize. Knowing her dad better than anyone else, Keiko knows that sometimes Kosen doesn’t say much during interviews, and yet, at other times, he does. Keiko not only helps as Kosen’s translator but also generally serves as the manager of his affairs, helping to evangelize his work while even she is getting to know him better. I am pleased to hear that she, too, wants to know what her dad makes of spirituality and ikebana’s ties to Buddhism, something that he hadn’t spoken of much while he was raising her. Keiko suggests that we plan a few meetings, over Zoom, to try to talk and to see which questions resonate the most with Kosen, and then to prepare more questions following that line of thinking for subsequent interviews. Rinse and repeat.

Kosen Ohtsubo, Willow Rain, 2025, 800 basket willow branches, metal frame, in: “Flower Planet,” Kunstverein München, Munich, 2024. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V. Photo: Maximilian Geuter.

Kosen Ohtsubo, Willow Rain, 2025, 800 basket willow branches, metal frame, in: “Flower Planet,” Kunstverein München, Munich, 2024. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V. Photo: Maximilian Geuter.***

When I first call Kosen Ohtsubo, the midmorning light is peeking in through the windows of his charcoal-black, stained-wood-floored studio in the Tokyo suburb of Tokorozawa. Keiko first answers the call, and as she goes off to find her father, I am left to stare at the walls of the studio through my Zoom screen, which more than slightly resemble a scene out of a darker version of Pee-wee’s Playhouse or Little Shop of Horrors. Designed by architect Hiroshi Nakao, Kosen’s abode is highly unique in its geometric nature as well as its use of ingeniously designed storage spaces: storing vases, books, records, and other materials. Among these units, alien tools are hung up on hooks (my mind jumps to The Far Side cartoon displaying bizarre, misshapen implements with the caption “Cow tools”), with different samplings of plants—familiar and unfamiliar—adorning the walls, and multicolored bubble letters saying “Flower Planet” barely in view. A dog barks. I learn that it is Keiko’s dog, named Tora, and that Tora is the Japanese word for “Tiger.” Soon enough, Keiko returns with her father.

Kosen Ohtsubo, Untitled (Wardrobe), October 1996, New Zealand flax, various garments, wire, wooden wardrobe, clothing hangers, radio-controlled car plastic cover. Inkjet print, 17 x 22 in. (43.2 x 55.9 cm.). Photo: Koichi Taniguchi.

Kosen Ohtsubo, Untitled (Wardrobe), October 1996, New Zealand flax, various garments, wire, wooden wardrobe, clothing hangers, radio-controlled car plastic cover. Inkjet print, 17 x 22 in. (43.2 x 55.9 cm.). Photo: Koichi Taniguchi.For close to five decades, Kosen Ohtsubo has been one of ikebana’s most unorthodox practitioners, blending Koten-ka (traditional ikebana) with bold and polarizing freestyle experimentation. Born in 1939, and raised in Ashio Dozan, which is in the central Tochigi Prefecture and home of the Ashio Dozan Copper Mine—the site of Japan’s first major pollution disaster in the 1880s and the scene of the 1907 miners’ riots—Kosen was the middle son of the village’s deputy mayor. Often left alone with little supervision, Kosen would wander through the nearby mountains as a child, sometimes even spending entire nights alone in nature. This initial push toward nature took further shape when Kosen, at an early age, quickly enrolled in ikebana lessons when a local woman first advertised them.

Literally meaning “living flowers,” ikebana has ancient roots dating back to India and China around the 6th century, yet the tradition is most commonly attributed to Japan, where it was codified around the time Buddhism was first introduced to the region from China. During this transmission, temples were built to house sculptures and artworks of the Buddha and other Buddhist deities, which often included offerings of flowers, incense, and food. The Rokkaku-do Buddhist temple in Kyoto is thought to be the birthplace of Japanese ikebana, with the earliest practitioners being Buddhist priests. In a piece for Buddhistdoor Global, author Meher McArthur notes how this Buddhist custom was quickly combined with Japan’s native Shinto animistic tradition of “using cuttings from evergreen plants to attract kami, or higher beings, to sacred sites.” The practice became secularized in the Muromachi period (c. 1336–1573)—with the introduction of the tokonoma alcove and chigaidana staggered shelves in the residences of the warrior elite in Kyoto—and yet it is hard to ever completely divorce the practice of ikebana from Buddhism as one of ikebana’s core aims, which is to show the impermanence of beauty, otherwise known as anicca in Buddhist teachings.

Kosen Ohtsubo, Untitled (Rikka of Cherry Blossom), ca. 2003, cherry blossom, pine, Japanese sacred lily. Inkjet print, 22 x 17 in. (55.9 x 43.2 cm.). Photo: Koichi Taniguchi.

Kosen Ohtsubo, Untitled (Rikka of Cherry Blossom), ca. 2003, cherry blossom, pine, Japanese sacred lily. Inkjet print, 22 x 17 in. (55.9 x 43.2 cm.). Photo: Koichi Taniguchi.With his childhood interest in ikebana piqued, by 1960, Kosen had moved to Tokyo to study in the prestigious Ikebana Ryusei-ha school, under the Ryusei master Kasen Yoshimura. He apprenticed under Kasen, earned the title of Master, and eventually became one of the school’s most notable practitioners. Gaining renown in the Meiji era, Ryusei-ha ikebana consists of combining a freer style (jiyuka), in which the arranger expresses his or her individual personality, with the classical styles carried on since the school’s founding, which includes the original style (rikka) as well as the classical three-branch form (seika), in which each stalk or stem is a different length, meant to represent either heaven, earth, or humankind. Rather than mimicking scenes one could have stumbled upon in nature, the forms of rikka and seika were supposed to be so intricate that they would appear almost beyond nature, evoking the image of what one might see upon attaining nirvana.

Openly anarchic, Kosen took to the freer aspects of the art form, increasingly leaning toward the experimentation of contemporary art, with notable influences from sculptor and filmmaker John Chamberlain, Donald Judd’s Primary Structures exhibition, The New York Earth Room, and Tokyo’s Mono-ha (School of Things). While Kosen is more than comfortable using cherry blossoms, chrysanthemums, and pine branches in his work, he will just as quickly reach for vegetables (both fresh and decaying) or refuse—think wilted cabbage, bits of scrap metal, piles of organlike daikon, mutilated rotten watermelon, or even his own body. Kosen’s bold embrace of experimentation and “outsider” ikebana runs counter to ikebana’s aristocratic and conservative leanings. From 1974 to 1977, Kosen was a member of The Group of Eight, a gathering of eight masters across a variety of ikebana schools who organized their own collective exhibitions until, concerned with the possibility of becoming a source of authority within ikebana themselves, disbanding and setting up Ikebana Kobouten, a public showcase that exhibited traditional ikebana artists alongside nonartistically trained participants, including musicians, electricians, and schoolteachers, among others. Now in his 80s, Kosen—widely known in art circles as “The Legend of Ikebana”–still teaches out of his house and home studio, a place and practice he officially dubs “Flower Planet.” (Kosen’s colleague, the incredible ceramicist Jun Kawaguchi, at one point made a number of ceramic signs all uniquely adorned with this name, many of which are found in and around Kosen’s home, drilled to walls and the building’s weathered reddish black raw corten steel exterior.)

Kosen Ohtsubo, 怪芋III / Strange Callas III, 2025, calla lily, willow, custom-designed iron box, in: “Flower Planet,” Kunstverein München, Munich, 2024. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V. Photo: Maximilian Geuter.

Kosen Ohtsubo, 怪芋III / Strange Callas III, 2025, calla lily, willow, custom-designed iron box, in: “Flower Planet,” Kunstverein München, Munich, 2024. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V. Photo: Maximilian Geuter.The following discussion took place over the course of three Zoom meetings in the fall and winter of 2024, occurring in the evening in New York City and the morning in Japan, often just after Kosen had finished teaching his morning classes.

***

Due to the ephemeral nature of your ikebana sculptures, photography plays a pivotal role in the reception of your work. And throughout your career, you have often placed yourself within the photographs of your ikebana. Do you view photography as documentation, or something more? How does the idea of observation fit into the manner in which you create your art, or, in general, in which you live your life? It is something more.

I was influenced by American installation artist Edward Kienholz. When I observe music or works by artists like Kienholz, I naturally feel that they share the same mindset and nature as I do. However, they haven’t directly influenced my decision to immerse myself in my own works, but they give me courage as kindred spirits.

Kosen Ohtsubo, Feeling High—Ikebana Bathing/I Am Taking a Bath Like This, 1984

Kosen Ohtsubo, Feeling High—Ikebana Bathing/I Am Taking a Bath Like This, 1984Kienholz’s production and ideas are similar to mine. He worked in a psychiatric hospital. An ikebana class is somewhat like a psychiatric hospital. When you observe the students closely, you can see their quirks and unique traits. Solving that is closely linked to arranging flowers.

An ikebana class is somewhat like a psychiatric hospital.

You have also mentioned your love of free jazz. How does jazz enter into your artistic practice, and who are some of your favorite artists? When I feel anxious, it’s not Japanese Zen philosophy that supports me. Rather, it’s people like Albert Ayler or Bill Evans that provide comfort. While my ears are not working as well as they used to, I used to listen to a lot of jazz. Instead of the morning alarm, I used to play Flight to Denmark by Duke Jordan. I also liked Albert Ayler, Bill Evans, Edmond Hall, and Astrud Gilberto. Listening to Albert Ayler, I can jump. Listening to Bill Evans’s piano, my mind goes wide and deep. Albert Ayler is a destroyer. Listening to Albert Ayler, I think I can destroy everything and consume what I think is best. For me, it’s something similar to meditation or a contemplative practice.

Do you think of yourself more as a destroyer—like Albert Ayler—or as wide and deep —like Bill Evans? Albert Ayler; he’s a destroyer.

Destruction does seem to permeate your work. Some of your pieces look violent—car crashes, smashed fruit, explosions, broken objects. What is the intention behind the violence in your work? Isn’t using a trained ikebana technique not all that compelling? Traditional skills and trained techniques may not necessarily lead to convincing works. Wouldn’t unrelated elements like violence or shock be more effective? I thought about incorporating such expressions into ikebana. Perhaps that would give ikebana the power to be more persuasive.

Do you consider yourself an aggressive person? Yes, I suppose so.

Kosen Ohtsubo, Car Crash, 1996

Kosen Ohtsubo, Car Crash, 1996Some of your work also seems to look almost tortured. I think of the works of directors like David Cronenberg, but instead of body horror, it is plant horror. How does horror fit into your aesthetic? I am interested in Cronenberg, but I haven’t watched his films, though I’ve just checked some scenes. I resonate with the idea of plant horror. I am not influenced by horror movies. It is more about the fear I feel from nature or the anxiety I experience personally. While I like famous filmmakers and horror writers, they don’t influence my work. There are, however, some pieces influenced by Junji Ito—including my spiral pieces; horror with a little bit of humor.

What makes Ito’s work fascinating is the idea that everyone has a spiral within them. Spirals can also be found in plants. Junji Ito drew the spirals in the ear. He envisioned spirals in boils too. I agree with Junji Ito. Both humans and plants have spirals. It gives me a sense that humans and plants are interconnected living beings. Junji Ito captures this shared essence in his manga, which is what makes his work so fascinating.

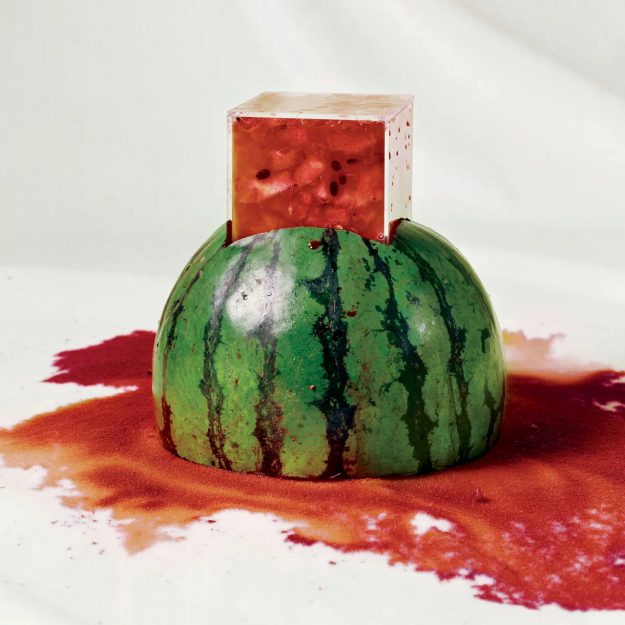

Kosen Ohtsubo, Oozing Out, 1976, acrylic box, watermelon, fabric. Photo first published in Ikebana Ryusei, September 1976. Photo: Ryusei photo department.

Kosen Ohtsubo, Oozing Out, 1976, acrylic box, watermelon, fabric. Photo first published in Ikebana Ryusei, September 1976. Photo: Ryusei photo department.Was there a specific moment when you first realized you had this connection with nature or that you wanted to use natural elements in your artistic practice? I grew up in the mountains, so whenever I had free time, I would wander around the mountains. Sometimes, I’d end up descending to a different town. There were times when I couldn’t find my way back, and I had to borrow money from the police to stay overnight. Wandering through the mountains without a map was one of my favorite pastimes as a boy. I had several hideouts in the mountains. They might have been animal dens. There were caves within bamboo groves where I would spend half a day.

Kosen Ohtsubo, 皆のっかってグッチャグチャ / Step on it, spring onion, steel, produced in May 1973, first published in Ikebana Ryusei magazine, July 1973, Photo: Ryusei photo department.

Kosen Ohtsubo, 皆のっかってグッチャグチャ / Step on it, spring onion, steel, produced in May 1973, first published in Ikebana Ryusei magazine, July 1973, Photo: Ryusei photo department.I believe those experiences have influenced my ikebana. These experiences happened on a low mountain, but one where it’s easy to get lost. I experienced the fear of not being able to find my way home many times. Yet it was so fascinating that I kept going back. The sense of wandering has had an impact. Free from rules.

Were there other childhood experiences that later influenced your ikebana practice? When the war started, I was just 5 years old. I lived far from Tokyo, so I never saw people die in front of me. My town was lucky. Refugees were kept there, so bombs couldn’t attack the town. I was born into a family who was managing a copper mine. My hometown was kind of a copper mine town, and there were many poor people working at the mines. I was surrounded by those people. I was an eyewitness to lots of unfairness in the copper mine town. I grew up in that unfair town, so anger or rage or protest was piled up inside of me.

As an adult, I feel that modern society resembles the world I saw as a child—unreasonable power, organizations. Anger and dissatisfaction have grown deep and large.

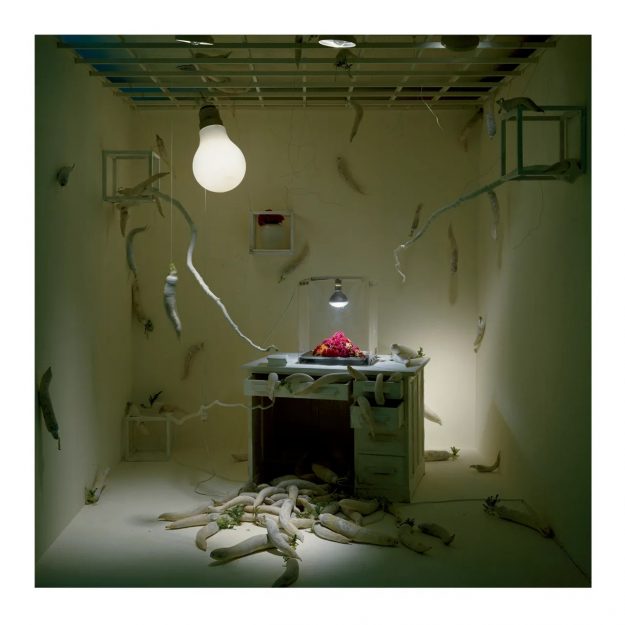

Kosen Ohtsubo, Radishes Wearing Makeup, October 1989, cockscomb, daikon radish, desk, huge electric bulb, hot dog warmer. Inkjet print, 17 x 16.9 in. (43.2 x 42.9 cm.). Photo: Koichi Taniguchi.

Kosen Ohtsubo, Radishes Wearing Makeup, October 1989, cockscomb, daikon radish, desk, huge electric bulb, hot dog warmer. Inkjet print, 17 x 16.9 in. (43.2 x 42.9 cm.). Photo: Koichi Taniguchi.You have been quoted as saying that you want to “destroy ikebana.” What did you mean by this? I want to disrupt the politics and environment within the ikebana industry.

In 1971, you caused a stir with your contribution to the Ryusei-ha’s annual exhibition where you gathered up plant clippings and trash left behind by other artists who were preparing their ikebana on-site, threw everything into a large canvas bag, and put that on display. Was this at all a comment on waste, pollution, or environmental degradation? Regarding the artwork with garbage bags, there was no intention of promoting waste reduction. Now, at ikebana exhibitions, waste is packed into cardboard boxes, but back then, garbage was stuffed into cloth bags. I found it horrifying. People gather at a place for the reason of arranging flowers, massively cutting living branches and leaves, putting them in bags, and turning them into trash. I thought of an ikebana exhibition as a horrifying slaughterhouse. I had no intention of stopping it; I just thought it was horrifying. I didn’t mean to judge it as good or bad; I just wanted to give it form.

Kosen Ohtsubo, Radish Death-Cotheque, cotton, daikon radish, metal shelving, plastic, produced in August 1994 and exhibited in “Ikebana as an Expression” in Nagoya Citizens’ Gallery, Aichi, Nagoya. Photo: Kosen Ohtsubo.

Kosen Ohtsubo, Radish Death-Cotheque, cotton, daikon radish, metal shelving, plastic, produced in August 1994 and exhibited in “Ikebana as an Expression” in Nagoya Citizens’ Gallery, Aichi, Nagoya. Photo: Kosen Ohtsubo.Some of your work almost looks like secret government photos, almost echoing something akin to Area 51. Are you playing around with the idea of government surveillance or secrets in your work? I have created works using components of national flags. I intentionally satirized the Japanese government. I believe my criticism of the Japanese government is justified. I created a work using a golden ball for the national flag. In Japan, it used to be common to display the national flag at the entrance of homes on public holidays, although this practice has become less common today. This golden ball was used for that purpose. However, in Japanese, “golden balls” is also a slang term for testicles. So my work was intended as a critique of Japan, the nation that initiated the war. That said, I don’t think even Japanese people would usually realize that this piece carries an antiwar message.

How important is satire in your work? Just a little. Ten percent.

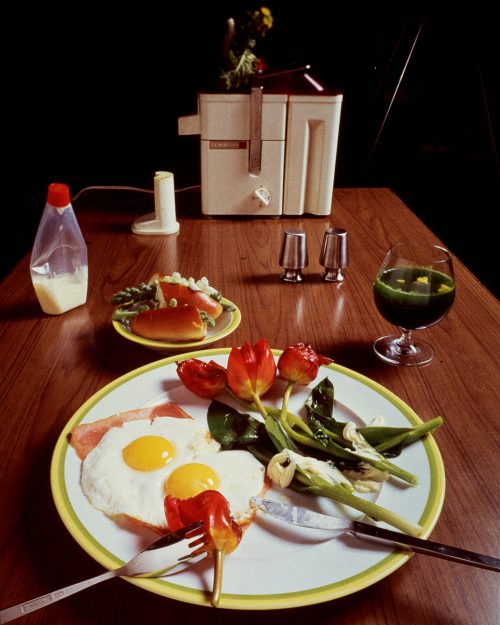

Kosen Ohtsubo, Mr. O’s Breakfast, 1973. Photo: Ryusei photo department.

Kosen Ohtsubo, Mr. O’s Breakfast, 1973. Photo: Ryusei photo department.You seem to blur the line between tradition and abstraction in your work. Is this a conscious effort? I intentionally maintain balance. I must be a champion of traditional ikebana techniques. I also serve as a judge for traditional ikebana exhibitions. It is precisely because I excel in traditional techniques that people respect even my destructive actions. When I do something unconventional, they trust that it has meaning. That is why I work diligently on traditional techniques—they enable me to undertake dangerous experiments.

Tradition is, more than anything, a tool for generating income—not just in ikebana but in everything. Tradition is a business.

If we preserve only what already exists, we cannot create new and meaningful expressions.

However, continuing to repeat the same traditions can ruin the art itself. That is why tradition should always be taught with a willingness to adapt and change. If we preserve only what already exists, we cannot create new and meaningful expressions. By breaking what has traditionally been considered good, we pave the way to create something new.

Kosen Ohtsubo, What Can You See?, 1974, glass, New Zealand flax, wool yarn. Photo first published in Ikebana Ryusei, April 1974. Photo: Ryusei photo department.

Kosen Ohtsubo, What Can You See?, 1974, glass, New Zealand flax, wool yarn. Photo first published in Ikebana Ryusei, April 1974. Photo: Ryusei photo department.Is something inherently more beautiful if it is subject to death, decay, or rot? Since ikebana uses live plants, it inherently involves rotten beauty. Especially now in summer, if we neglect to change the water in the vase for even a day, the flowers may still look beautiful, but the lower stems in water get covered in slimy textures, and the cut ends turn a light brown. Whenever I try to keep cut flowers in good condition, I always feel like I’m in a race against the bacteria. And when the rot becomes too overwhelming, I feel a sense of resignation, as if I’m up against something I can’t fight!

In my work, I use cabbage leaves a lot. I have observed the changing states of the leaves and used them in my works. Cabbage leaves are very good at capturing the state of a plant’s life. You can clearly see how they change. They show the transformation of a living organism. It’s beautiful but also frightening. Cabbage is very mundane. It’s always at home. By continuously observing the state of cabbage and creating works from it, I may be hinting at the future of the earth. Using such materials to create artworks might make the audience think a lot about the future. If a large wall were made out of such cabbage, the very act might evoke not only fear but also hope. Building a considerably large wall with masses of cabbage and observing the changes in the cabbage would be a way to collectively feel the future of the earth.

Poetry, especially haiku, is also concerned with the ephemeral. Are you influenced at all by poetry? I like poetry, haiku, and tanka, and have read a lot of them. It is certain that they have had a comprehensive influence. I don’t often create works influenced by specific pieces. However, influenced by Takahama Kyoshi’s haiku about radishes, I created a series of works featuring radishes.

“Flowing on by,

the leaves of radishes.

What swiftness!”

Buddhism is also concerned with the impermanence and ephemeral nature of reality. And I know that ikebana shares some of its roots with Buddhism. Do you see your ikebana as inherently Buddhist? When foreigners look at me, they might sense Zen or martial arts within me. That perception might be due to Buddhism. I’m not a devout follower, but I’ve been deeply influenced by it on a profound level. However, I prefer Indian Buddhism over Japanese Buddhism.

One-third of my ikebana is Koten-ka (classical ikebana styles that follow strict principles passed down through centuries, including rikka and shoka). I teach that to earn a living. Classical Koten-ka is not just about technique. The fundamental idea of classical Koten-ka is prayer. It should be arranged with the feeling of putting palms together (gassho), which is the same as Buddhism. I feel that the essence of Buddhism is prayer and putting palms together. Classical Koten-ka without this lacks impact. In this respect my ikebana, especially my classical Koten-ka, is conscious of Buddhism and values the central line.

Kosen Ohtsubo, Play with Funnels, golden lily of the valley, fox face, plastic funnel, c. 1990s. Photo: Ryusei photo department.

Kosen Ohtsubo, Play with Funnels, golden lily of the valley, fox face, plastic funnel, c. 1990s. Photo: Ryusei photo department.Putting palms together represents feeling one’s limits, praying to gods and Buddhas, and continuing to hope despite enduring everything. I believe that classical Koten-ka is empowered by Buddhism.

Modern people who arrange classical Koten-ka often lack the feeling of Buddhist prayer, and I think that without it, the works cannot be imbued with strength. Putting palms together is to continue wishing for something even if it is beyond one’s capability. I believe that is the power of classical Koten-ka. No matter how classical Koten-ka may change in the future, without the spirit of putting palms together, it will not result in good works.

Putting palms together is to continue wishing for something even if it is beyond one’s capability. I believe that is the power of classical Koten-ka.

In Buddhism, it is said that chanting the nembutsu solves all problems. Buddhism is taught this way. Through this, people have overcome suffering. Arranging flowers and putting palms together share a similar essence. Even without making the gesture of putting palms together, one can do so in their heart. That is the foundation of classical Koten-ka. I believe that the essence of Buddhism is putting palms together, and I think the same holds true for the essence of classical Koten-ka.

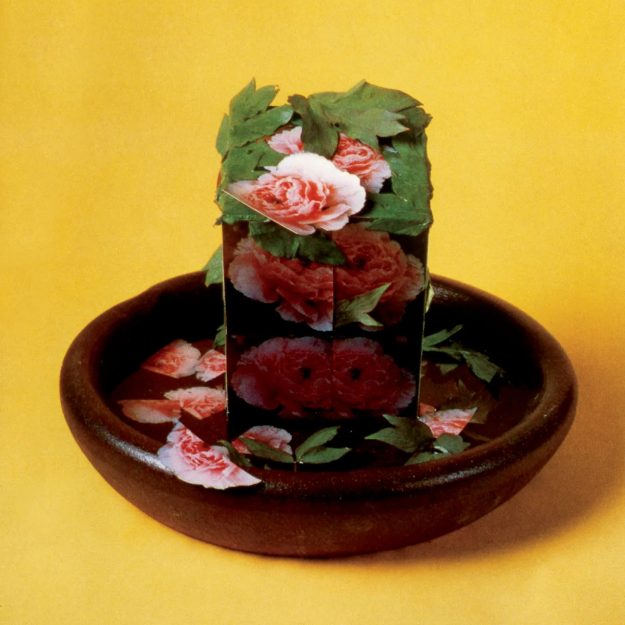

Kosen Ohtsubo, Peony Illusion, 1978, peony leaves, photographs. Photo first published in Ikebana Ryusei, June 1978. Photo: Ryusei photo department.

Kosen Ohtsubo, Peony Illusion, 1978, peony leaves, photographs. Photo first published in Ikebana Ryusei, June 1978. Photo: Ryusei photo department.You also reference the linga symbol a lot within your work. Where does this fascination with the linga stem from? I have visited the banks of the Ganges many times, seeing numerous lingams and corpses. I naturally found myself joining my hands in prayer before the lingams.

Do you have any personal connection to India? I was surprised to learn when the Beatles went to India. They met with musicians there and created great music. At that time, there was a trend where artists believed everyone should go to India. Inspired by the Beatles’ trip, I thought I could spark an amazing personal revolution by going to India myself, so I went there alone. The Beatles had a significant influence on me.

I have visited the Tibetan Plateau four times. Tibetan Buddhism is very similar to Indian Buddhism, and mandalas are a common element. Representations of lingam and yoni can be found everywhere along the paths in India, where people worship and offer flowers. In 1973, just after Keiko was born, I went to India. About sixteen years later, we both went to England and visited Liverpool. And after visiting Liverpool, I visited India again. I have traveled to India five times in total.

Lotus flowers also show up a lot in your work, and are used as a common motif in both Buddhism and Hinduism. A good lotus is born from the remains of dead plants. Mud itself is composed of decayed plants. While this has no direct influence on my works, good mud is essential for growing healthy plants—mud is the mother of all good plants.

Kosen Ohtsubo, リンガ正月 / Linga New Year, narcissus, pine, various flowers, produced in January 1985. Photo: Ryusei photo department.

Kosen Ohtsubo, リンガ正月 / Linga New Year, narcissus, pine, various flowers, produced in January 1985. Photo: Ryusei photo department.I frequently use lotuses in classical arrangements, often as offerings to Buddha. In Beijing, arranging lotuses was very easy. They were readily available in flower markets, grown in large basins. In Japan, however, they are much harder to obtain. The lingam and lotus are also connected in my works, sharing a profound relationship. They are linked through the theme of prayer. Prayer is deeply related to Buddhism.

Do you pray at all? In my everyday life, I never pray or meditate, but in my mind, I pray when I create my pieces. For me, that is Buddhism.

Kosen Ohtsubo, Untitled (Bell Pepper Linga), August 2017, bell pepper, small chrysanthemum, ceramic container made by Thomas Edward Sellen. Inkjet print, 14.7 x 22 in. (37.3 x 55.9 cm.). Photo: Koichi Taniguchi.

Kosen Ohtsubo, Untitled (Bell Pepper Linga), August 2017, bell pepper, small chrysanthemum, ceramic container made by Thomas Edward Sellen. Inkjet print, 14.7 x 22 in. (37.3 x 55.9 cm.). Photo: Koichi Taniguchi.Do you think art has the ability to change people’s minds? Yes. However, I am not intentionally trying to change people’s hearts. I do, however, want to remind people to question whether the idea that traditional techniques are always the best still holds true today. I aim to create works that provoke such thoughts. The traditional methods of expression in training are closely tied to pride and authority, which I dislike. We need to challenge that. New artists must fight against the authority that has been established before them.

UsenB

UsenB

![We’re Bringing The SEJ Newsroom To You, Live [Free Event] via @sejournal, @hethr_campbell](https://cdn.searchenginejournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/sej-live-ap-2-974.png)

_1.jpg)