Microplastics in Seafood and Cancer Risk

Plastic particles may exacerbate the pollutant contamination of fish. “Plastic debris in the marine environment is more than just an unsightly problem.” The concern is […]

Plastic particles may exacerbate the pollutant contamination of fish.

“Plastic debris in the marine environment is more than just an unsightly problem.” The concern is not so much discarded bobbing bottles, but the tiny microplastic particles, which raises questions about cancer. What does plastic have to do with cancer? As I discuss in my video Are Microplastics in Seafood a Cancer Risk?, in the 1950s, researchers observed that when they wrapped the kidneys of rats with cellophane (to cause high blood pressure), they inadvertently ended up causing cancer. Cancers started growing around the cellophane. When the researchers tried slipping different plastics under the skin of rodents, they found that each of them could produce malignant tumors. In addition, if you feed rats plastic microbeads, up to 6 percent of the particles end up in their bloodstream within 15 minutes.

Could all of this microplastics pollution be one of the reasons we’re seeing an increased number of tumors found in wildlife? “Perhaps the global increase in wildlife cancers is a ‘wake-up call’ at the right time.”

We don’t know if it’s the plastic itself or some of the chemical additives, like bisphenol A (BPA), that are to blame. Maybe having plastic particles stuck in your body causes some sort of mechanical irritation beyond “the chemical impact of the plastics as carriers of possible carcinogens into organisms.” Some plastics may be cancer-causing in and of themselves, but all “[p]lastic debris readily accumulates harmful chemicals,” such as persistent pesticides like dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and flame-retardant chemicals, “increasing their concentration by orders of magnitude. This process is reversible, with microplastics releasing contaminants upon ingestion…” So, plastic debris may act as a vector, transferring persistent, bioaccumulative, and toxic substances “from the water to the food web.” “Plastics are known to concentrate pollution from the water column by factors of up to 1 million times”—PCBs, for example. In fact, one of the ways environmental scientists sample for contamination levels is by using plastic to sponge up pollutants.

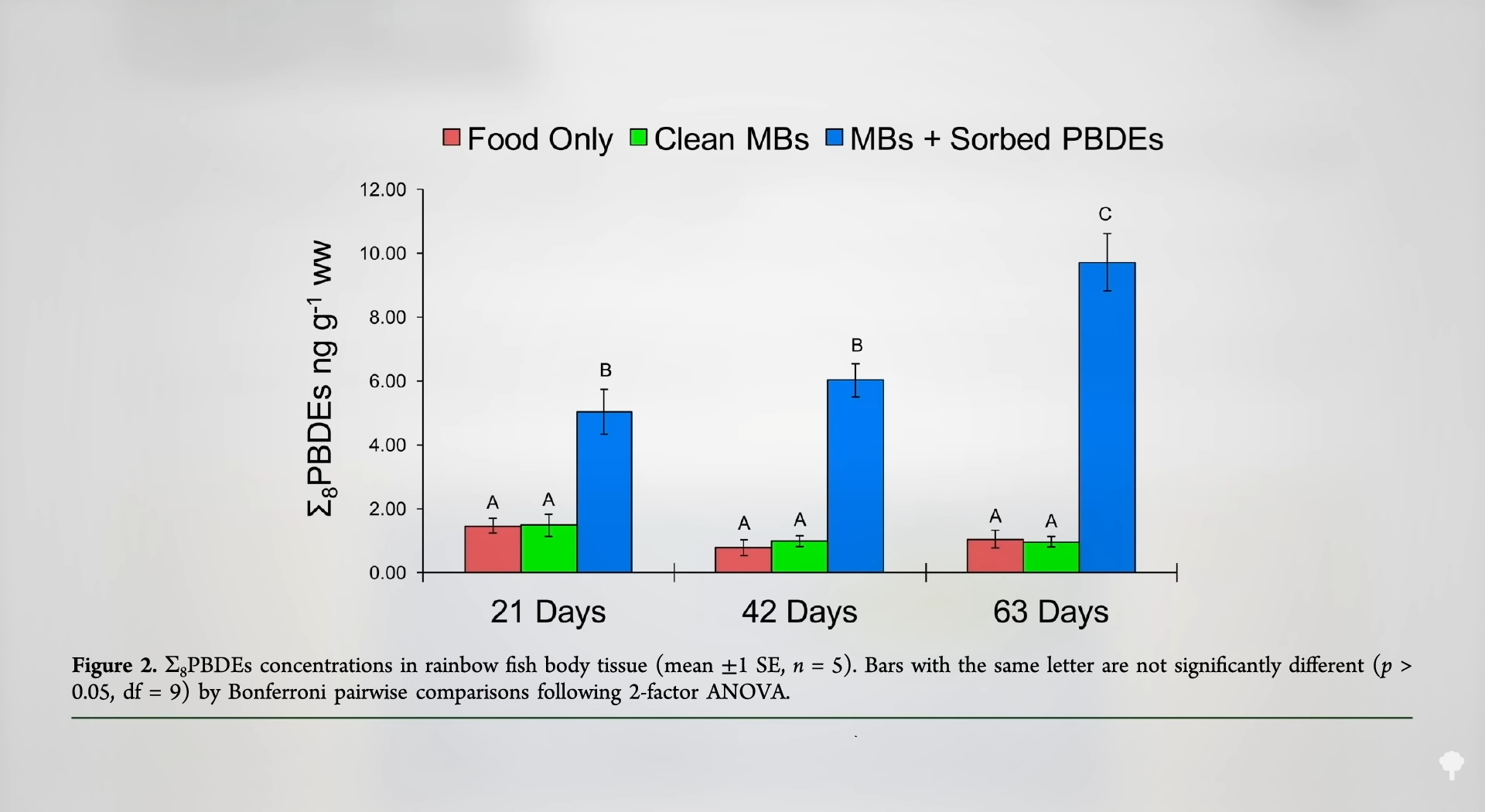

The concern is that the plastic takes up all of these toxins and then deposits them into the aquatic food chain, where they can climb up, possibly, ultimately, into humans. This was all theoretical until researchers confirmed it. Chemical pollutants were found to glom on to microbeads from personal care products that were then ingested by fish and accumulated in the animal. The longer you feed polluted microbeads to fish, the higher the levels of contamination in their flesh. As you can see in the graph below and at 2:31 in my video, pollutant levels can concentrate up the food chain with maximum exposure in the apex predators, like killer whales or people. The herring eats a bunch of brine shrimp. The cod eats a bunch of herring. The halibut or tuna eats a bunch of cod. And, finally, humans eat the halibut and tuna.

We know ingested plastic can transfer hazardous chemicals to fish, which then accumulate and can cause liver toxicity and pathology in the fish, but what happens in people? We know that in the United States, of all food categories, fish have the highest levels of PCBs, dioxins, and other pollutants. We don’t eat a lot of fish in this country, though, so is it really a problem?

It’s hard to come up with a tolerable daily intake of these kinds of chemicals, but the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends staying under one to four units a day (measured in picograms of toxic equivalents). The European Union came up with a smaller number: no more than two units a day on average. In the United States, we’re already past that, “so there is some concern for toxicity from PCBs at current levels of PCBs and plastic debris polluting the ocean. There is no ‘room’ for additional PCB burden,” so what can we do about it?

We can practice the three Rs by reducing, reusing, and recycling plastic items—for example, shopping with reusable tote bags. On a policy level, we could ban the use of plastic microbeads in cosmetics and personal care products. Ideally, all countries would do it, since plastic debris dropped anywhere on earth may end up being transported to the ocean, where it can travel around the world. “Whatever strategies are adopted, international cooperation will be critical in limiting the risk to the oceans and the risk to humans from eating seafood.”

To learn more about microplastic pollution, see my videos Microplastic Contamination and Seafood Safety and How Much Microplastic Is Found in Fish Fillets?.

KickT

KickT