Obesity and a Toxic Food Environment

Implausible explanations for the obesity epidemic serve the needs of food manufacturers and marketers more than public health and an interest in truth. When it […]

Implausible explanations for the obesity epidemic serve the needs of food manufacturers and marketers more than public health and an interest in truth.

When it comes to uncovering the root causes of the obesity epidemic, there appears to be manufactured confusion, “with major studies reasserting that the causes of obesity are ‘extremely complex’ and ‘fiendishly hard to untangle,’” but having just reviewed the literature, it doesn’t seem like much of a mystery to me.

It’s the food.

Attempts at obfuscation—rolling out hosts of “implausible explanations,” like sedentary lifestyles or lack of self-discipline—cater to food manufacturers and marketers more than the public’s health and our interest in the truth. “When asked about the role of restaurants in contributing to the obesity problem, Steven Anderson, president of the National Restaurant Association stated, “Just because we have electricity doesn’t mean you have to electrocute yourself.” Yes, but Big Food is effectively attaching electrodes to shock and awe the reward centers in our brains to undermine our self-control.

It is hard to eat healthfully against the headwind of such strong evolutionary forces. No matter what our level of nutrition knowledge, in the face of pepperoni pizza, “our genes scream, ‘Eat it now!’” Anyone who doubts the power of basic biological drives should see how long they can go without blinking or breathing. Any conscious decision to hold your breath is soon overcome by the compulsion to breathe. In medicine, shortness of breath is sometimes even referred to as “air hunger.” The battle of the bulge is a battle against biology, so obesity is not some moral failing. It’s not gluttony or sloth. It is a natural, “normal response, by normal people, to an abnormal situation”—the unnatural ubiquity of calorie-dense, sugary, and fatty foods.

The sea of excess calories we are now floating in (and some of us are drowning in) has been referred to as a “toxic food environment.” This helps direct focus away from the individual and towards the societal forces at work, such as the fact that the average child is blasted with 10,000 commercials for food a year. Or maybe I should say ads for pseudo food, as 95 percent are for “candy, fast food, soft drinks [aka liquid candy], and sugared cereals [aka breakfast candy].”

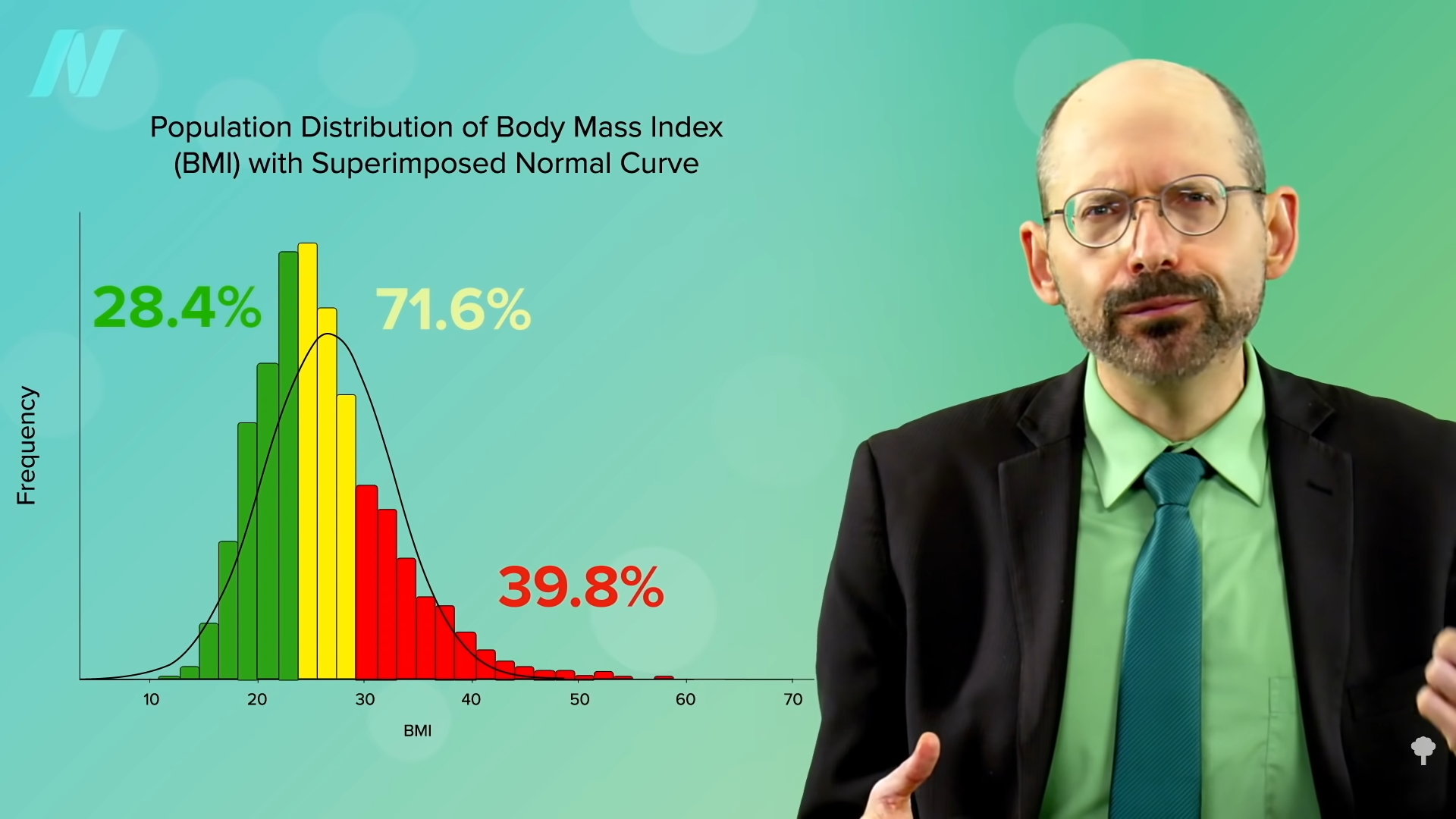

Wait a second, though. If weight gain is just a natural reaction to the easy availability of mountains of cheap, yummy calories, then why isn’t everyone fat? As you can see below and at 2:41 in my video The Role of the Toxic Food Environment in the Obesity Epidemic, in a certain sense, most everyone is. It’s been estimated that more than 90 percent of American adults are “overfat,” defined as having “excess body fat sufficient to impair health.” This can occur even “in those who are normal-weight and non-obese, often due to excess abdominal fat.

However, even if you look just at the numbers on the scale, being overweight is the norm. If you look at the bell curve and input the latest data, more than 70 percent of us are overweight. A little less than one-third of us is normal weight, on one side of the curve, and more than a third is on the other side, so overweight that we’re obese. You can see in the graph below and at 3:20 in my video.

If the food is to blame, though, why doesn’t everyone get fat? That’s like asking if cigarettes are really to blame, why don’t all smokers get lung cancer? This is where genetic predispositions and other exposures can weigh in to tip the scales. Different people are born with a different susceptibility to cancer, but that doesn’t mean smoking doesn’t play a critical role in exploding whatever inherent risk you have. It’s the same with obesity and our toxic food environment. It’s like the firearm analogy: Genes may load the gun, but diet pulls the trigger. We can try to switch the safety back on with smoking cessation and a healthier diet.

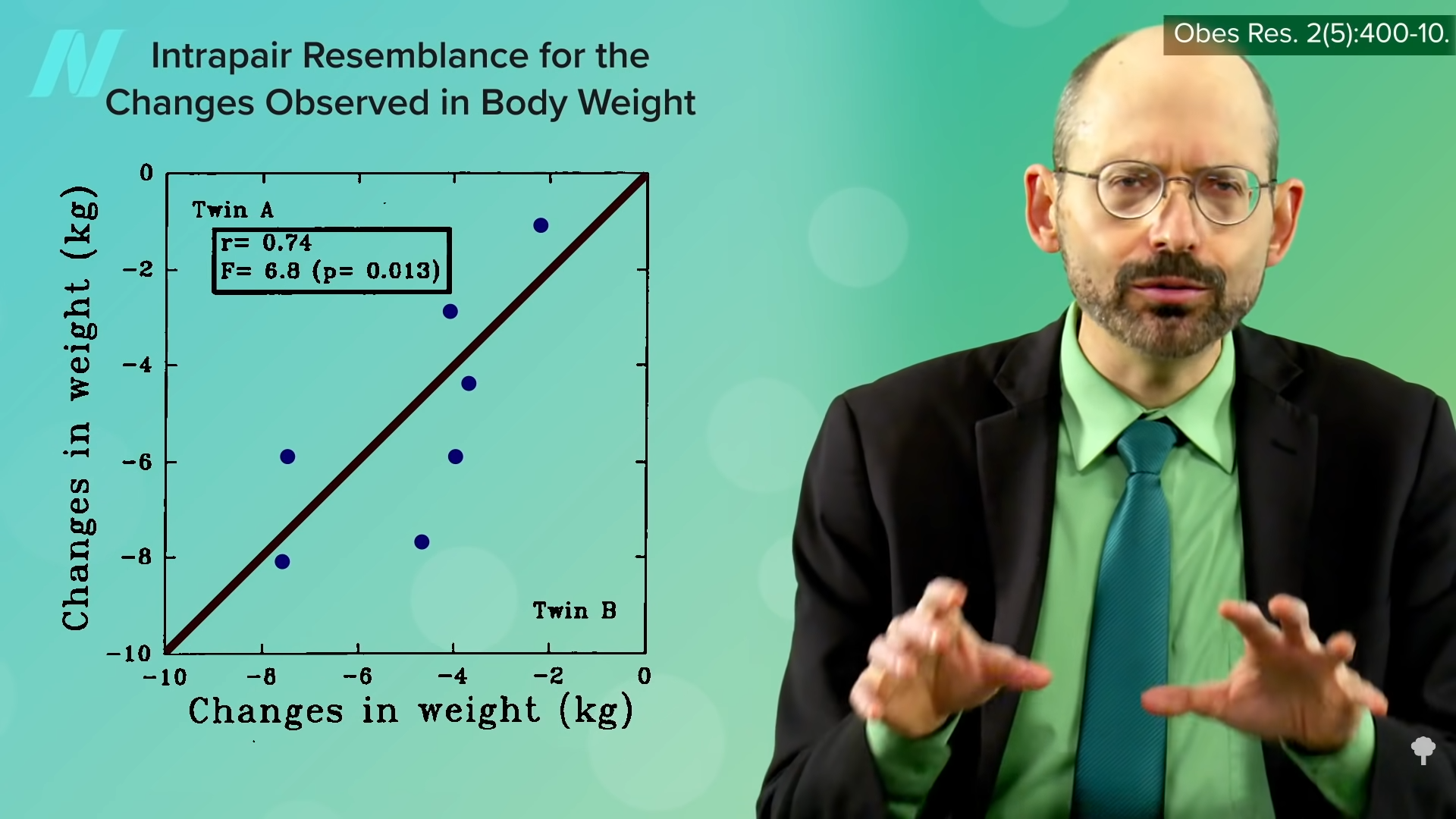

What happened when two dozen study participants were given the same number of excess calories? They all gained weight, but some gained more than others. Overfeeding the same 1,000 calories a day, 6 days a week for 100 days, caused weight gains ranging from about 9 pounds up to 29 pounds. The same 84,000 extra calories caused different amounts of weight gain. Some people are just more genetically susceptible. The reason we suspect genetics is that the 24 people in the study were 12 sets of identical twins, and the variation in weight gain between each of them was about a third less. As you can see in the graph below and at 4:41 in my video, a similar study with weight loss from exercise found a similar result. So, yes, genetics play a role, but that just means some people have to work harder than others. Ideally, inheriting a predisposition for extra weight gain shouldn’t give a reason for resignation, but rather motivation to put in the extra effort to unseal your fate.

Advances in processing and packaging, combined with government policies and food subsidy handouts that fostered cheap inputs for the “food industrial complex,” led to a glut of ready-to-eat, ready-to-heat, ready-to-drink hyperpalatable, hyperprofitable products. To help assuage impatient investors, marketing became even more pervasive and persuasive. All these factors conspired to create unfettered access to copious, convenient, low-cost, high-calorie foods often willfully engineered with chemical additives to make them hyperstimulatingly sweet or savory, yet only weakly satiating.

As we all sink deeper into a quicksand of calories, more and more mental energy is required to swim upstream against the constant “bombardment of advertising” and 24/7 panopticons of tempting treats. There’s so much food flooding the market now that much of it ends up in the trash. Food waste has progressively increased by about 50 percent since the 1970s. Perhaps better in the landfills, though, than filling up our stomachs. Too many of these cheap, fattening foods prioritize shelf life over human life.

But dead people don’t eat. Don’t food companies have a vested interest in keeping their consumers healthy? Such naiveté reveals a fundamental misunderstanding of the system. A public company’s primary responsibility is to reap returns for its investors. “How else could we have tobacco companies, who are consummate marketers, continuing to produce products that kill one in two of their most loyal customers?” It’s not about customer satisfaction, but shareholder satisfaction. The customer always comes second.

Just as weight gain may be a perfectly natural reaction to an obesogenic food environment, governments and businesses are simply responding normally to the political and economic realities of our system. Can you think of a single major industry that would benefit from people eating more healthfully? “Certainly not the agriculture, food product, grocery, restaurant, diet, or drug industries,” wrote emeritus professor Marion Nestle in a Science editorial when she was chair of nutrition at New York University. “All flourish when people eat more, and all employ armies of lobbyists to discourage governments from doing anything to inhibit overeating.”

If part of the problem is cheap tasty convenience, is hard-to-find food that’s gross and expensive the solution? Or might there be a way to get the best of all worlds—easy, healthy, delicious, satisfying meals that help you lose weight? That’s the central question of my book How Not to Diet. Check it out for free at your local library.

This is it—the final video in this 11-part series. If you missed any of the others, see the related posts below.

Konoly

Konoly