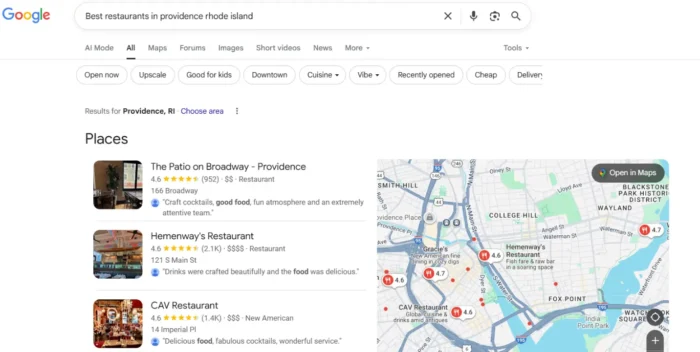

Practice for a World at Risk

It’s the concept of “other” that drives the evils the world suffers from, says Roshi Joan Halifax. The contemplation we need now is that in reality there is no separation. The post Practice for a World at Risk appeared...

It’s the concept of “other” that drives the evils the world suffers from, says Roshi Joan Halifax. The contemplation we need now is that in reality there is no separation.

Photo by Vince Bevan / Alamy Stock Photo

As I witness all that is happening today—armed conflict in the heart of Europe, global pandemic, rising authoritarianism, impending climate catastrophe, and all of life’s other sufferings and injustices—I am acutely aware, as you probably are, that our world is at risk.

We might ask: How can we meet this reality of suffering and violence? What is the task ahead of us to meet confusion, delusion, and violence in our time, in our country, in our lives? How do we realize peace transformation?

Buddhism guides us to realize the most radical form of inclusivity — that all beings can be free of suffering and delusion, and we are not separate from any of them.

Vaclav Havel once said that morality means taking responsibility—not only for our own life, but for the life of the world. From a Buddhist perspective, that means understanding that we are not separate from all beings and things, and acting accordingly. It means we cannot give in to the tendency to turn the world and its beings into objects we call “other.”

Buddhism has since its very beginning guided its practitioners to realize the most radical form of inclusivity—the realization that all beings, in all realms, no matter how depraved and deluded, can be free of suffering and delusion, and that we are not separate from any of them.

So the teachings of the Buddha tell us that there is no “other.” The basic vows we take as Buddhists remind us that there is no “other.” Yet we live in a world peopled by those who are subject to the deepest forms of alienation from their own natural wisdom, a world where whole communities see “others” who should be done away with, liquidated, eliminated, raped, ravaged, cut down, and gunned down.

When there is “other,” there is an Auschwitz, a caste of people we will not touch, a ravaged and raped woman, a clear-cut forest, an abused and abandoned child, a man behind bars, a village of old women whose men have all died in war, a fearful young conscript from Russia with a gun in his hand, Ukrainian civilians killed by bombs and rockets from the sky. Without “others” there are none of these things.

Photo by Matt Palmer.

Peace transformation is realizing—and living—nonalienation from all beings on our earth. This is the realization of bodhisattvas as they ride on the waves of birth and death, working compassionately to relieve the suffering of all beings.

If we see we are not separate from others, then we not only share their awakening, we also share their suffering. I am not separate from the suffering of Ukrainians, but also I am not separate from the suffering of those who have attacked Ukraine. In the experience of nonseparation, I open, bear witness, and hold as much as I can with a strong back and soft front.

It is not so easy to realize this truth of interdependence, or “interbeing” as Thich Nhat Hanh called it. Many of us have not allowed ourselves to look deep inside to see and touch who we really are. Yet Buddhists and contemplatives of many traditions have long been guided to go within to discover the interconnectedness of all things and the peace that surpasses ideas and concepts. This peace is basic to all beings when they come home to a state of nonalienation. Because this wise peace is not complacent, nor is it restless, it nourishes courageous and compassionate action in the world.

Peace transformation is grounded in an experience of connection and radical intimacy with the world. It is about the realization that awakening is not an individual experience. It is liberation in our intimate relatedness with and through all beings.

Awakening, then, is ultimately social. Buddhists serve and awaken in and through relationships based in a deeply shared life, one that is dedicated to nonaggression and benefitting every being and thing on our planet.

We can nurture peace by transforming our own lives. At the same time, we must reach out courageously to where the suffering is most acute, sending our voice, taking a stand, and making peace by strengthening values, views, and behaviors that are based in the great treasures of compassion and wisdom. We must work actively for nonviolence toward all, and for deep and true dialogue that respects differences and plurality. And we must take our own responsibility. We have to ask: what is our part, and our country’s part, in feeding the demons of hatred and aggression?

As Buddhists, we share an aspiration to awaken from our own confusion, greed, and anger in order to free others from suffering. The bodhisattva vows at the heart of the Mahayana tradition are a powerful expression of what I call “wise hope,” of hope against all the odds. This is the kind of hope that is victorious over fear and hopelessness. For how else could we chant the impossible aspiration:

Creations are numberless,

I vow to free them.

Delusions are inexhaustible,

I vow to transform them.

Reality is boundless,

I vow to perceive it.

The awakened way is unsurpassable,

I vow to embody it.

Now, more than at any other time in our lives, may we realize these vows in word and deed.

Aliver

Aliver