Remembering My Child

Grieving the death of her only son, a mother unexpectedly finds awakening. The post Remembering My Child appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

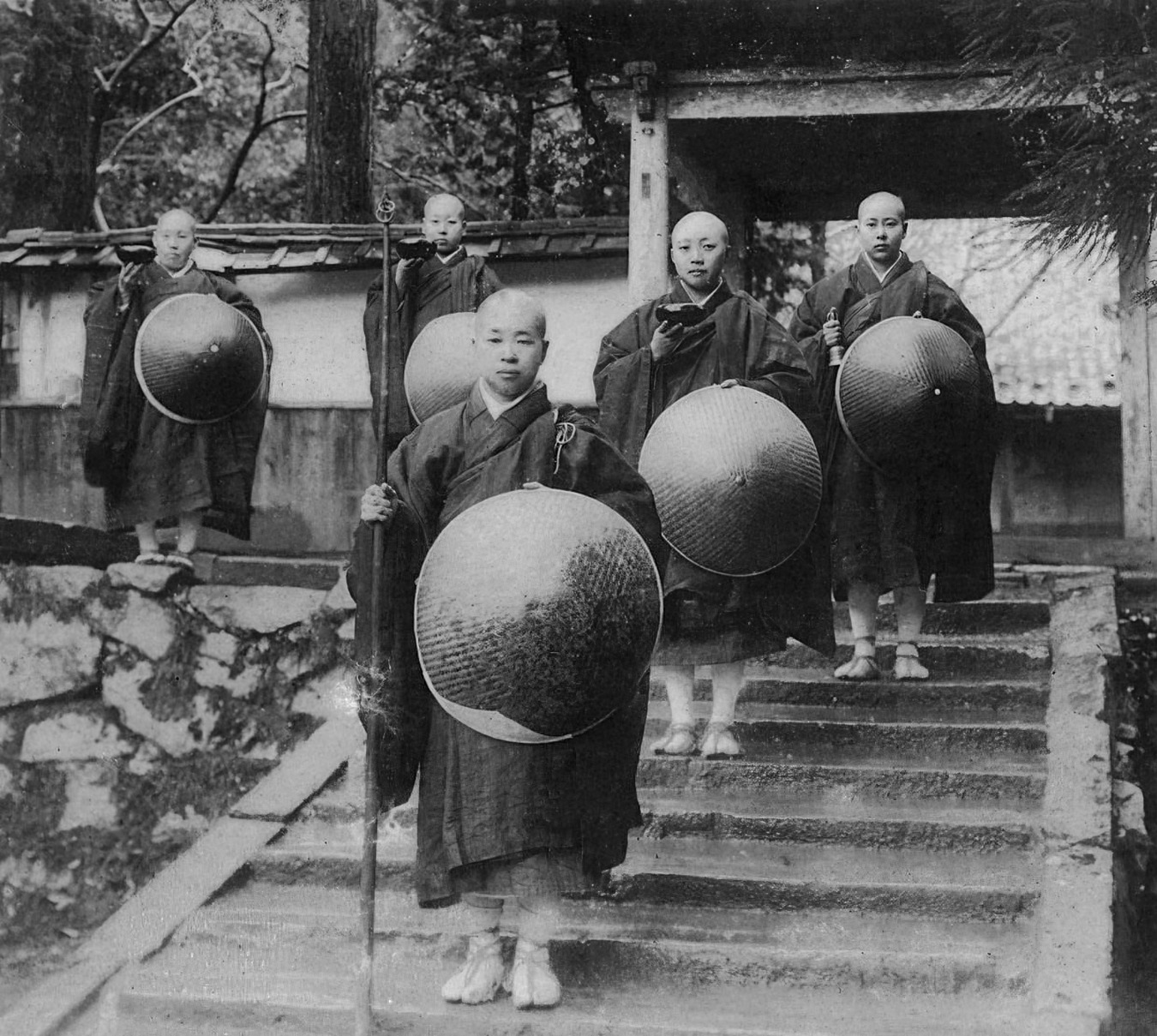

The following excerpt is from In This Body, In This Lifetime: Awakening Stories of Japanese Soto Zen Women, a collection of stories by thirty students of the Zen master Sozen Nagasawa Roshi (1888–1971). The only independently teaching female Zen teacher of her time, Nagasawa Roshi trained generations of nuns and laywomen in World War II–era Japan. Whenever one of her students had a kensho experience, she encouraged them to write down their story. Here is the awakening story of Momoyo Nakayama, a laywoman who went on to become a senior practitioner at Kannon-ji.

***

I lost in the war my beloved only son, for whom there is no replacement in heaven or on earth. Just three days after graduating from Tokyo Imperial University, he left for the front in high spirits to serve as a reservist. In the Philippines, the lifetime of this mere sapling of 26 was ended.

May 7, 1945, was a day I won’t ever be able to forget. It is when I received the remains of my son’s body, returned ceremonially, with the news of his death in war. I cannot express the grief and anguish I felt when I held in my arms this small box made of plain wood, even in such words as “I felt like vomiting blood” or “I was in heartrending grief.” Only other mothers who have experienced this can know the feeling.

From a world of light, I was thrown into a world of darkness. I lost all desire to live. All my happiness was taken away. I had devoted my life to raising this son, often alone, as my husband was a foreign missionary, absent for long periods in a temple in Hawaii. I had taken such delight in my beloved child’s growth. For him to reach adulthood was my one great goal, the only light and hope of my life. Whatever pains and sorrows that arose along the way amounted to nothing—my life had been vibrant like an always full moon. Now I lived in grief, empty like a soulless puppet, devastated by the loss of my child, grieving day and night. I don’t know how many times I thought to follow my beloved child into death, but each time when I was about to do it, I would clearly hear his dear voice saying, “Mom, you must not die. Please be happy. Please live in happiness.”

My son didn’t want me to suffer or die. I just had to cry until it was enough. People criticized me as a foolish mother, a prisoner of my emotions. I had fallen as low as one can. In the morning and the evening I would make a ceremonial food offering, chant a sutra, and offer incense and flowers before his spirit. This brought me some consolation, but I continued in this wretched state day and night for over three years. I had taught over two thousand children and had guided many young mothers, but now my life was in a pitiful state.

Finally, I met Sozen Nagasawa Roshi of Kannon-ji, the nuns’ training monastery, and listened to one of her talks. At first I thought, How could a nun who has never given birth or raised a child, let alone had her child be killed, ever understand this pain, this suffering? There is no one in this world I can turn to. My heart remained shut tight. However, as I listened to her, I was deeply moved by her character. There was some untouchable intensity about her. At the same time, she had a childlike innocence that pulled me toward her. I thought, She is different from the other nuns I have met so far. I was gradually drawn in more and more by her lectures and started to think maybe I would give zazen a try.

I went at first for two days of sesshin, then three days, and finally I completed a whole seven-day sesshin. As one retreat followed another, my own foolishness keenly sunk into my mind. I realized that although Roshi didn’t have the experience of giving birth to a child, raising him, and having him die, from the perspective of practice, she possessed exalted experience surpassing that of the mothers of the world. She was strict and fierce, and yet the shining light of her great compassion guided this community—composed of very different people—with complete mastery. This was the true mind of compassion! I resolved that I would train under her and break through the ultimate barrier.

From then on, I pushed forward in a literal do-or-die struggle, relying entirely on Roshi. However, I soon discovered breaking through is easier said than done. During sesshin, the suffering, sorrow, anxiety, and misery I experienced were beyond words. People who haven’t done this kind of retreat cannot imagine or know the agony of it. I jumped into this world of practice as a beginner, not knowing anything about it.

In the pursuit of Mu I didn’t change my meditation posture and I didn’t sleep. I lost sensation in my whole body from the pain in my legs, and sparks would fly out of my eyes. Even as I was in a continuous struggle that felt like a thousand deaths and a million hardships, without any mercy, I was hit hard from behind.

It was the first time in my life that I had ever been hit by someone, and in that instant I thought, How barbaric! My resistant mind started to heat up, and I went to dokusan furious and crying. “Don’t try to argue! It’s just your ego attachment!” the Abbess roared, and she chased me away with the ringing of her bell.

Mu-, Mu-, Mu-! I grappled with Mu with all my might. But even while I was desperately putting my life on the line, I would just hear, “That’s just emotion!” “That’s an excuse!” “That’s an explanation!” “What are you dawdling over?” As I was scolded thoroughly, my beliefs and ideas were being destroyed. Mu-, Mu-, Mu-!—whether sleeping or during the meal, while in the toilet—only Mu-, Mu-, Mu-!

With the passage of time, I lost my appetite. I couldn’t sleep at night, and I just sat up in meditation, the exhaustion of my body and mind reaching an extreme. During kinhin (walking meditation), I couldn’t take even a single step. I was seized by Mu, tormented by Mu. I was crying out Mu, yet I could not grasp Mu. During dokusan I was told, “That’s makyo (hallucination)!” “That’s belief!” “That’s an idea!” “Don’t intoxicate yourself with dharma joy!” It was an unbearable, ruthless, sharp whip of words. I had exhausted all means, and I had nothing to hang on to. Thrown down and sunk to the very bottom, I felt that there was no hope for me anymore and that I was a sinful person completely without the right to be saved. I even thought, My son disappeared with the dew on the battlefield, but his anguish couldn’t be worse than his mother’s is now.

Sometimes, in my ignorance and in vain hope, I relied on Roshi—a true teacher of the Way—to save me. Other times I just wanted to run from the temple as fast as I could. Once I went to my room crying, even packing my bags—when from the very bottom of my heart a voice came, saying, Under the skies of a foreign country far from his motherland, without anything to drink or to eat, hiding in the fields, sleeping in the mountains, how many times did my son dream of his hometown? Surely he wanted to see his father and mother and his beloved only sister. What was the state of mind of this child of mine who died a noble death? He cut off the self-interest that is so difficult to sever and knew the preciousness of life while having no way to go forward and, if that was his superiors’ orders, no way to retreat—I must think of my child’s death in battle! What is my suffering in comparison? It is not even anything worth mentioning. If I, his mother, won’t realize the Way now, when will my dead son and I ever be saved from this world? Instantly the intention to run away vanished, and with great inspiration and renewed courage, I continued my practice.

Until then I had been trapped, enclosed in a narrow and hard shell, unable to move. With the progress of the practice my self-centeredness started to recede. And freed from distracting thoughts, gradually I was able to break out into an expansive, bright world. From the bottom of my heart I could prostrate myself in gratitude for a single slice of pickled radish, one grain of rice in the gruel, or even the intense whip.

As the wife of a priest, I had eaten Buddha’s food, I had been taught the dharma and read Buddhist books, and it seemed I had grasped it theoretically. But now I was ashamed, and I couldn’t bear the remorse. I was made painfully aware that unless I endured the hardships of practice and really experienced awakening myself, in a time of crisis, it was all of no use. This really soaked into the marrow of my bones.

Encouraged, I went to dokusan, but once again I was told, “You’re just finding dharmic pleasure in the world of faith! Why are you so stingy? Come out! Come out! Come and grasp Mu. Don’t hesitate! Reveal yourself completely. Come out and grasp it! Come on! Come on!” Sitting face to face, the Abbess kept poking me with the kyosaku. There was nothing I could hold on to. What agony!

Here where I find myself, there is only death . . . it is death, it is Mu, it is death, it is Mu, it is Mu, it is Mu! Forget about dokusan! Mu-, Mu-, Mu-! There is only Mu! I went out into the garden and quietly sat. In front of the temple there was a large tree, almost reaching to the clouds. Harmonizing with my Mu-, Mu-, Mu-!, the tree was making the earth tremble, urging me on. All the flowers and every single azalea leaf were talking to me. At night, the brilliant moon became one with me, laughing.

Morning came. How pleasant was the morning practice, how clear the little bird’s song was! The sound of the cutting board of the temple’s cook was so crisp—chop, chop, chop. The sound of the mallet of the elderly lady living behind the temple cracking open soybean pods—everything was an exquisite piece of music that no words in the world could describe. I guess this is what it means to go to the Pure Land, the greatest joy, I thought. There was no longer the troublesome Saha world (world of suffering), nor was there the Venerable Abbess. The clinging to my beloved dead son had disappeared, as had the painful pursuit of Mu, in this samadhi of dharma joy.

However, once again, I was startled by the roar of the Abbess, and a Whack! Whack! Whack! of the stick. I was instructed to return to Mu. Again, Mu-, Mu-, Mu-! A tiny bug landing on the paper screen; it was Mu. An airplane flying through the sky; it was Mu. The whole universe was nothing but Mu. The paper screen in front of me started to dissolve, and I couldn’t see anymore. My body felt as if it were being pulled into the deep bottom of the earth.

When the bonsho (temple bell) rang, in that instant, suddenly, I broke through! I realized that heaven and earth are one; myself and the universe are one body. Buddha is what I am! There is only unity. Everything is Mu. This great treasure I grasped has not even a gap for a feather to pass through. No one could ever harm it—it transcends even death. The Venerable Abbess herself could not damage or destroy it.

This great treasure I grasped has not even a gap for a feather to pass through. No one could ever harm it—it transcends even death.

It is perfect, it is perfect, it is perfect. Even the Venerable Abbess probably didn’t reach this far, I thought, and I was finally able to go to dokusan as the original self, imperturbable. For the first time, the Venerable Abbess smiled warmly and approved my experience. Then she gave me various guidelines and cautions.

My joy disappeared as I was made aware of the responsibility and trials of a person aspiring to the Way. Now I deeply understood the words of encouragement the Venerable Abbess had been telling me: “Don’t intoxicate yourself with dharma joy.” I was presented with another koan to further refine my state of mind.

Compared to how I had been living—inside the narrow, hard shell of my own suffering—this is a different world. And although it is a path of trials, and the adversities one has to overcome to reach the state of mind of all buddhas and ancestors are immeasurable, actually walking this path is the greatest joy.

The timeless, indestructible life is continuously bestowing me with each moment. Here, living and working together with my dead son is a joy that cannot be expressed in words. This is the Buddha-mind, that is the Buddha-mind—there is nothing that is not the Buddha-mind. This is joy, that is delight. My life is complete and overflowing in this fresh, pure, vast heaven and earth.

During a lecture, Roshi said,

Like a clear dew,

my mind

if placed on an autumn leaf

just as it is—a ruby.

When my mind is colorless and transparent, no matter what circumstances arise, I can adapt to them. I have started a new life, a life worth living, where with each step I am repaying the kindness of buddhas and ancestors. And while I won’t ever be able to forget the austerities of sesshin, I have only the deepest gratitude for all the troubles that the Venerable Abbess took to teach me. I can only put my hands together in gassho.

♦

Adapted from In This Body, In This Lifetime © 2025 by Sozen Nagasawa Roshi (Author), Esho Sudan (Editor), Kogen Czarnik (Translator), Paula Arai (Foreword). Reprinted in arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc. Boulder, CO. www.shambhala.com.

Tekef

Tekef