Rooted like Teak: The Growing Strength of the Thai Bhikkhuni Sangha

Long excluded from Theravada society, a network of female monks is quietly transforming Thailand’s religious landscape. The post Rooted like Teak: The Growing Strength of the Thai Bhikkhuni Sangha appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

“The Thai Bhikkhuni Sangha is like a teak tree,” said Venerable Dhammananda Bhikkhuni. “It takes time to grow, but once its roots are deep, it becomes strong and offers great benefits to the community.” Like the sturdy teak that takes decades to mature, Thailand’s community of bhikkhunis—fully ordained Buddhist women—has grown slowly, pushing through challenges to establish itself in a Thai Theravada Buddhist tradition that has previously excluded them.

On September 27, 2025, that tree stretched farther and grew taller. Ven. Dhammananda, the first Thai woman to receive full Theravada ordination, convened the country’s first Thai Bhikkhuni Sangha Seminar on “Intergeneration and Sustainability” at Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok. The gathering brought together more than one hundred bhikkhunis and samaneris (novice nuns) from eighteen provinces, along with monks and lay supporters. Over five sessions—with four devoted to the challenges and opportunities facing Thai bhikkhunis—participants shared their stories, strategies, and hopes for the future of women’s monastic life in Thailand. In between, there was a session featuring a Thai musical show from Chulalongkorn University and a puppet show on Queen Mahaprajapati. the Buddha’s stepmother and the first bhikkhuni, played by the children from Baan Home Hug Foundation, an orphanage founded and run by Ven. Suthasinee Noi-in since 1989.

The modern Thai bhikkhuni movement began in 2003, when certain women—including Ven. Dhammananda—received full ordination despite resistance from the official monastic hierarchy, which considers the Thai (or Theravada) bhikkhuni lineage to have died out centuries ago. The Sangha Supreme Council of Thailand (Maha thera samakom) insists that the Theravada bhikkhuni tradition cannot be revived due to the lack of legitimately ordained monastics. According to them, a valid ordination for bhikkhunis needs ordination from both monks and nuns who have been ordained legitimately in the Theravada lineage. As Theravada Buddhism has not had any nuns for many centuries, there are no legitimate nuns to ordain more bhikkhunis. In addition, the Thai Sangha has forbidden monks to ordain bhikkhunis since 1928.

Against criticism and institutional opposition, bhikkhuni hopefuls have continued their work—quietly but steadfastly—building a foundation for future generations of ordained Buddhist women. Today, there are around 280 bhikkhunis practicing in thirty-three monasteries and five affiliated branches across the country. Most were ordained in Sri Lanka or India, where Theravada bhikkhuni lineage has been revived, while others with fewer resources have received ordination from the Santi Asoke movement, an unrecognized reform sect in Thailand. This movement deviates from the practices of the Sangha, rejecting the worship of Buddha images, maintaining a certain level of strictness in morality, and highlighting doing everyday work as a genuine example of practicing the dhamma. In response, the Sangha Supreme Council of Thailand has accused Santi Asoke as being a subversive movement that threatens the well-being of Buddhism.

Bhikkhunis choose to focus not on what they are denied but on what they can offer—to the dhamma and to others in need.

September’s Thai Bhikkhuni Sangha Seminar opened with a panel titled “Perspectives of the Four Buddhist Communities on Bhikkhunis,” bringing together voices from each of the four traditional Buddhist assemblies—bhikkhus (monks), bhikkhunis (nuns), laymen, and laywomen. Although the bhikkhuni lineage has been reestablished in Thailand for more than twenty years, all four speakers agreed that women’s ordination remains fragile and uncertain.

Among the panelists was Venerable Suchart (Phra Khru Wateedhammawitat), abbot of Wat Laem Pho in Songkhla province. Known affectionately as a “brother” to many bhikkhunis, he is one of the few monks who publicly supports their presence in Thai Buddhism. During his sermons, he often mentions his bhikkhuni disciples and encourages listeners to visit their nunneries. Through these talks, ordinary Thais—sometimes for the first time—learn that bhikkhunis exist and are practicing in their own country.

Ven. Suchart suggested that the Bhikkhuni Sangha could expand by establishing more nunneries throughout Thailand. He acknowledged their challenges but expressed confidence in what he called “the natural strength of women.” Drawing on his experience in the Muslim-majority south, he observed that bhikkhunis often integrate more easily into diverse communities than monks. “They can talk to anyone,” he said, “and they help many women. Sometimes they do more than monks, who may reach out only when material incentives are involved.”

Ven. Dhammananda added that the Buddha himself envisioned women’s ordination as essential to the completeness of the Buddhist community. Citing the Mahaparinibbana Sutta, she reminded listeners that the Buddha considered the sangha fulfilled only when it included all four groups: monks, nuns, laymen, and laywomen. Even if the bhikkhuni order is not officially recognized in Thailand, she said, its presence brings the tradition closer to the Buddha’s original vision.

The second session, “Overcoming Challenges and Obstacles for the Thai Bhikkhuni Sangha,” focused on the daily realities of bhikkhunis across Thailand—how they adapt to their surroundings and find ways to sustain their communities against the odds. Most nunneries have been built from scratch in remote areas, often without electricity or running water. With little financial support and limited recognition from local laypeople, the bhikkhunis shoulder the full burden of creating and maintaining their own spaces for practice.

Bhikkhunis at Wat Songdhammakalyani. | Photo via Pornrak Chowvanayotin and from the students of the Faculty of Fine and Applied Arts, Chulalongkorn University.

Bhikkhunis at Wat Songdhammakalyani. | Photo via Pornrak Chowvanayotin and from the students of the Faculty of Fine and Applied Arts, Chulalongkorn University.

During this session, Venerable Silananda, abbess of Silananda Nunnery in northeastern Thailand, described her early struggles. Raised in Bangkok, she found life in the countryside difficult at first: The food was unfamiliar, and villagers’ practices were more focused on ritual, celebration, and offering dana, paying less attention to learning and practicing the buddhadhamma. To gain acceptance, she and her community have had to adapt to local customs without abandoning their own priorities. “We still have only a small number of devotees,” she said, “but they are sincere. They come to learn and practice the dhamma with us—and that is enough.”

In Uthai Thani province, in central Thailand, Venerable Dhammavijjani shared a different experience. Her nunnery lies along a Thudong route, a traditional forest pilgrimage path used by monks. Because locals were already accustomed to supporting wandering renunciants, they also welcomed the bhikkhunis with alms and donations. Yet, she observed, the giving was often more about generosity than learning: “They are happy to give,” she said, “but less interested in receiving and practicing the dhamma.”

For Venerable Dhammakamala, who first ordained as a mae chi (a white-robed lay nun who keeps eight or ten precepts) before becoming a bhikkhuni, the transition was painful. When she wore white robes, people greeted her with smiles and offered her food during alms rounds. But when she donned the saffron robes of a fully ordained nun, the reception turned cold. “That first morning,” she recalled, “I received no food—only insults.” Her photograph was posted online, and local monks denounced her as fraudulent, insisting that “there are no bhikkhunis in Thailand.” Similar incidents have occurred elsewhere: One bhikkhuni was even detained at an airport because police claimed that wearing the monk’s robe was illegal for women.

These experiences, Ven. Dhammakamala said, are taken as tests of faith. “Dhamma flourishes because of obstacles,” she told the audience. Many bhikkhunis see adversity as an opportunity to strengthen their practice—an external reflection of the inner struggle against sankharas, or mental conditioning. “The path is not easy,” Ven. Silananda added, “but it is doable.”

To navigate such challenges, bhikkhunis emphasize humility and respect in their relationships with local monks. In new areas, it is customary for them to first pay a visit to the abhidhammika (monk authority) to introduce themselves and ask for guidance. “We approach monks as elder brothers,” one bhikkhuni explained, “and they, ideally, protect us as younger sisters.” By bowing first, seeking counsel, and offering help, bhikkhunis hope to foster understanding, gain community support, and show that they are not rivals but partners in preserving the Buddha’s teachings. In addition, bhikkhunis choose to focus not on what they are denied but on what they can offer—to the dhamma and to others in need. Many see the bhikkhuni path as a refuge for women who have faced hardship, offering them spiritual discipline, community, and purpose. “The Buddha hesitated to ordain his stepmother not because she was a woman,” Ven. Dhammananda reflected, “but because the path of renunciation is difficult for anyone.”

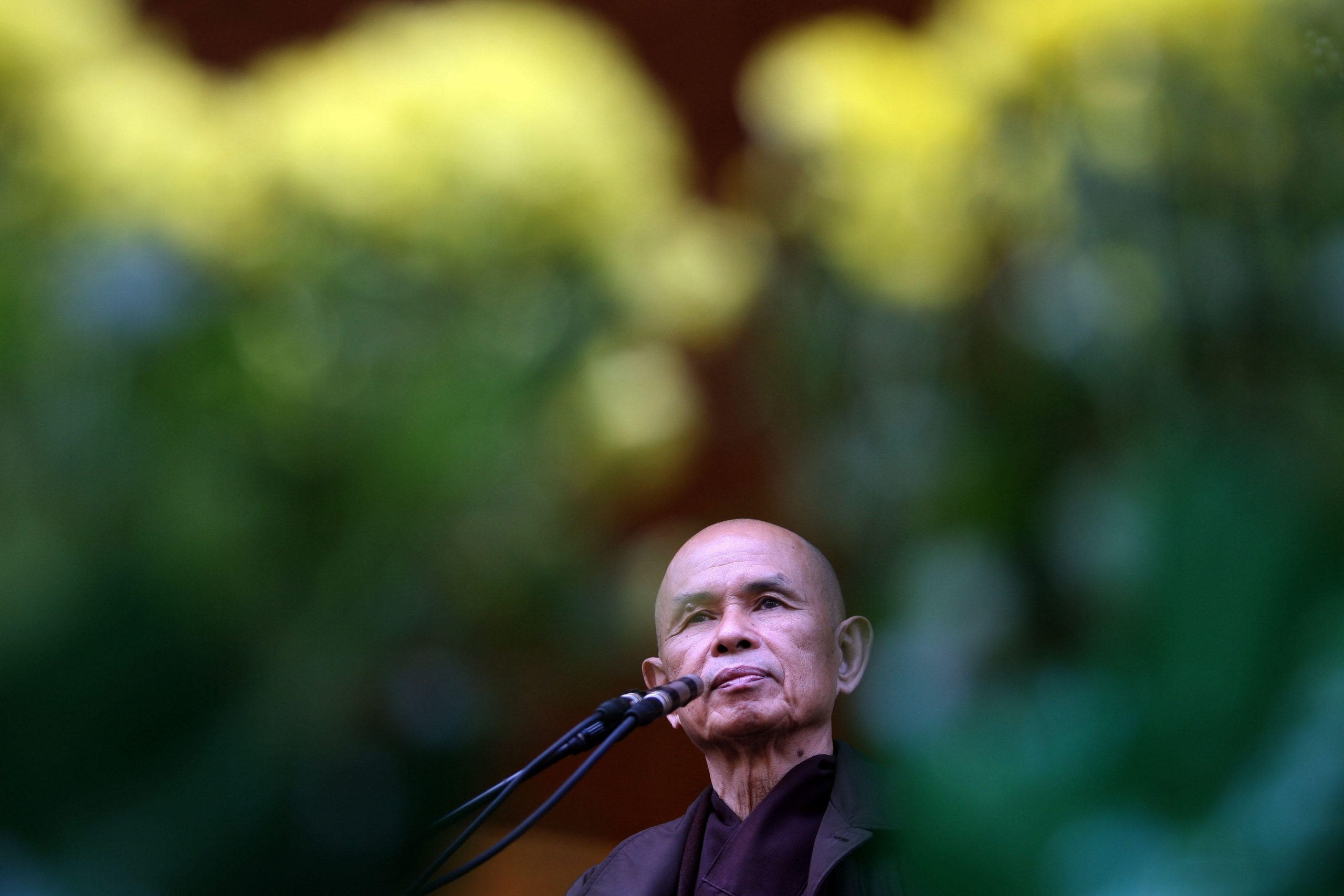

Venerable Dhammananda Bhikkhuni at an international conference in St. Ottilien, Germany. Venerable Dhammananda Bhikkhuni is considered the first Thai woman to be fully ordained in the modern Theravada tradition and has been instrumental in reestablishing the bhikkhuni order in Thailand. | Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Venerable Dhammananda Bhikkhuni at an international conference in St. Ottilien, Germany. Venerable Dhammananda Bhikkhuni is considered the first Thai woman to be fully ordained in the modern Theravada tradition and has been instrumental in reestablishing the bhikkhuni order in Thailand. | Image via Wikimedia Commons.

The final session turned to the future: how to pass on knowledge and practice to the next generation of bhikkhunis. Venerable Supanya from Nong Khai province in northeastern Thailand spoke about the importance of bhikkhunis supporting one another. In her nunnery, where there was once no electricity, running water, or even a road, she received both financial help and spiritual guidance from Ven. Dhammananda. When ordination ceremonies take place, senior bhikkhunis who are qualified to confer novice ordination (samaneri) travel long distances to assist.

Nowadays, the acceptance from local communities has improved; however, Thai bhikkhunis still face structural exclusion. They remain unrecognized by both the Thai Sangha Council and the state, which means they lack access to official monastic education and to the privileges enjoyed by monks. During a small breakout session, sixty bhikkhunis from twenty-two nunneries gathered to request a formal curriculum in vinaya (monastic discipline) and dhamma study. In this way, they believe that the knowledge and lineage of bhikkhunis could be sustained and passed on to a younger generation. Their appeal to have both vinaya and dhamma study as a fundamental aspect of the bhikkhuni development underscores both their devotion to practice and their wish to get their community established and growing strongly. “The world of bhikkhunis was closed for 700 years,” one participant said. “We must hold each other’s hands tightly and keep growing together as a united bhikkhuni sangha.”

The seminar closed with warmth and solidarity, leaving participants with renewed encouragement, a sense of sisterhood, and the conviction that, like the teak tree, the Bhikkhuni Sangha will continue to grow—slowly, steadily, and strongly. In Buddhism, teak is highly valued for its grounding aromatic properties as well as for its durability and resilience, all essential qualities in the spiritual journey toward enlightenment. If given more institutional and public support so that it gets recognized and rooted, the Thai Bhikkhuni Sangha could serve as a beacon of stability for countless women monastics to come.

Hollif

Hollif