Russia debt default prospect resurfaces as U.S. blocks bond payment

The prospect of a Russian debt default has once again been brought to the fore after the U.S. Treasury blocked dollar-denominated debt payments from Moscow via U.S. banks.

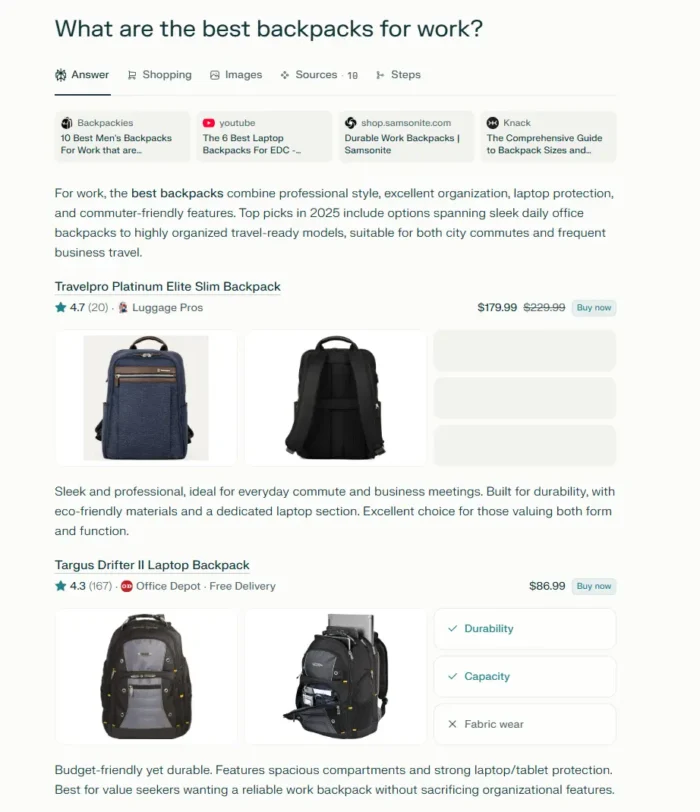

Russian President Vladimir Putin attends a meeting with members of the Security Council at a residence outside Moscow, Russia April 1, 2022.

Mikhail Klimentyev | Sputnik | Reuters

The prospect of a Russian debt default has once again been brought to the fore with the U.S. Treasury blocking dollar-denominated debt payments from Moscow via U.S. banks.

The move on Monday evening prevents the Kremlin from paying holders of its sovereign debt with the more than $600 million of dollar reserves held with U.S. financial institutions, and is aimed at forcing Russia to either use up more of its own stockpile of dollar reserves or accept a first debt default in decades.

Sanctions imposed following Russia's invasion of Ukraine on Feb. 24 had already frozen all foreign currency reserves held by the Central Bank of Russia with U.S. banks, but the Treasury Department had permitted Moscow to use those funds to meet coupon payment obligations on its dollar-denominated debt on a case-by-case basis.

"Russia is facing a recession, skyrocketing inflation, shortages in essential goods, and a currency that no longer works in much of the world," a U.S. Treasury spokesperson told CNBC on Tuesday.

The spokesperson added that one of the "most potent" actions of the 700+ sanctions the U.S. has imposed had been those levied on the CBR with "unprecedented multilateral coordination, speed, and impact."

A $552.4 million principal payment on a bond maturing in 2022 and an $84 million coupon payment on a 2042 sovereign dollar bond came due on Monday, a day after allegations emerged that Russian forces had massacred civilians in towns around the Ukrainian capital of Kyiv.

"Today is the deadline for Russia to make another debt payment. Beginning today, the U.S. Treasury will not permit any dollar debt payments to be made from Russian government accounts at U.S. financial institutions," the Treasury Department spokesperson said.

"Russia must choose between draining remaining valuable dollar reserves or new revenue coming in, or default."

The spokesperson added that the drawdown on dollars would further deplete the resources available to Russian President Vladimir Putin's war effort and trigger greater uncertainty in the Russian financial system.

'Putin will need to think long and hard'

Russia has thus far avoided defaulting on its foreign currency debt despite tough Western sanctions limiting the central bank's access to foreign exchange reserves. The U.S. Treasury Department had previously said that sanctions enforced against Russia did not bar the country from making good on its international debt payments, at least until May 25 when an exemption was due to expire.

The U.S. and Europe are now readying yet more sanctions following the allegations about civilian killings.

The Russian defense ministry and the Russian embassy in London have not yet responded to CNBC's request for comment.

Timothy Ash, an emerging markets strategist at BlueBay Asset Management, called the Treasury's move a "logical next step."

"Putin will need to think long and hard now whether he wants to avoid a formal default on external debt, which will have negative consequences for the Russian economy for years to come," he said in a research note.

"In reality, unless Putin withdraws from Ukraine it is hard to see Russia avoiding default here, unless it does something like transport planes of physical cash dollars or gold West, but even then it's hard to see any international bank being willing to provide for settlement for bondholders to avoid default. And indeed whether international bondholders would want to accept settlement."

Moscow failing to service its debt would mark Russia's first sovereign default since 1998, when it defaulted on domestic debt, and the first sovereign default on foreign currency debt since the Bolshevik Revolution in 1918.

—CNBC's Sam Meredith contributed to this article.

Koichiko

Koichiko