Russia may aspire to a China-style internet, but it's a long way off

As Russia moves toward a highly censored and tightly controlled internet amid its invasion of Ukraine, citizens are finding ways to bypass restrictions.

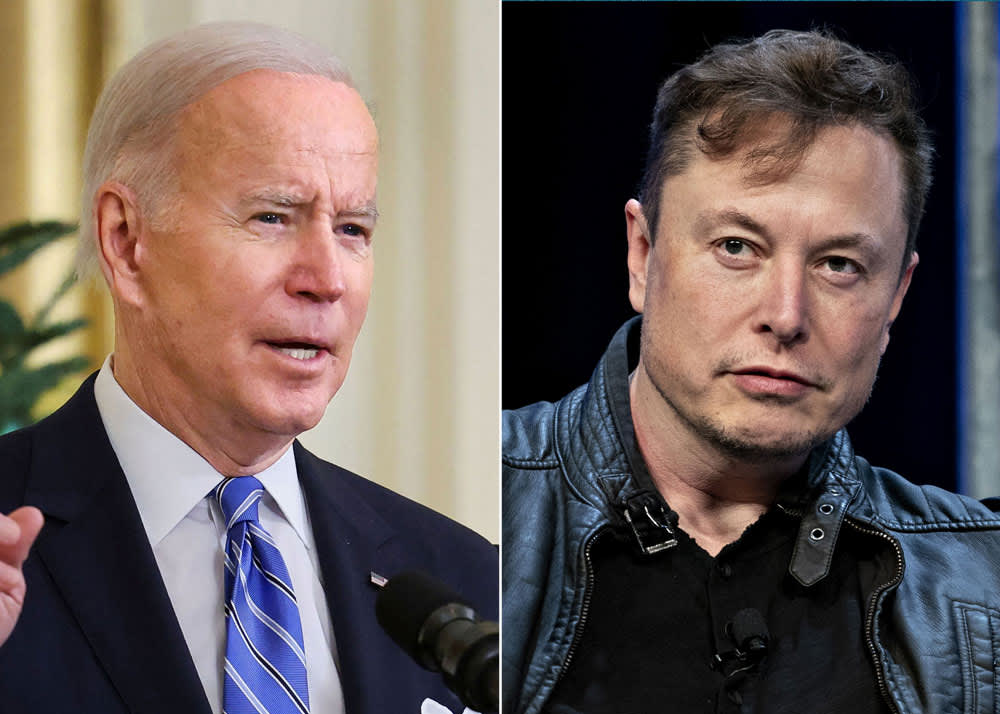

Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping pose for a photograph during their meeting in Beijing, on Feb. 4, 2022.

Alexei Druzhinin | AFP | Getty Images

As Russia's war on Ukraine continues, Moscow has looked to tighten control over its domestic internet, cutting off apps made by U.S. technology giants, even while other firms have pulled their own services from the country.

But a move to emulate the internet as it exists in China — perhaps the most restricted online environment anywhere — is a long way off, and Russian citizens are still manage to bypass controls in the system, analysts told CNBC.

Over the last few years, companies like Facebook owner Meta, Google and Twitter have operated in an uneasy environment in Russia.

They have faced pressure from the government to remove content the Kremlin deems unfavorable. The Washington Post reported this month that Russian agents threatened to jail a Google executive unless the company removed an app that had drawn the ire of the President Vladimir Putin. And companies have lived under threat of their services being throttled.

While Russia's internet became progressively more controlled, citizens could still access those global services, making them gateways to information other than state-backed media or pro-Kremlin sources.

But the war with Ukraine has thrust American technology giants into the cross-hairs once more, as Putin's desire to further control information increases.

Instagram is now blocked in Russia after its parent company Meta allowed users in some countries to call for violence against Russia's president and military in the context of the Ukraine invasion. Facebook was blocked in Russia last week after it put restrictions on government-backed news outlets. Access to Twitter is heavily restricted.

Those incidents highlight how Big Tech companies have to balance their pursuit of a large market like Russia with increasing demands for censorship.

"For Western tech companies, they made a strategic decision at the beginning of the conflict to support Ukraine. This puts them on a collision course with the Russian government," Abishur Prakash, co-founder of the Center for Innovating the Future, told CNBC. He added that companies like Meta are "picking politics over profits."

Russia's Ministry of Foreign Affairs and its media and internet watchdog Roskomnadzor did not respond to a request for comment when contacted by CNBC.

'Russia cannot do this overnight'

Russia's tightening online grip has revived talk about a "splinternet" — the idea that two or more divergent internets will operate in increasingly separate online worlds.

Nowhere is that separation clearer than in China, where services from Google, Meta, Twitter and foreign news organizations are blocked.

Instead of WhatsApp, Chinese citizens use WeChat, the popular messaging app with over 1 billion users, for example. Google search is replaced by Baidu. Weibo replaces Twitter.

The country's massive censorship system, known as the Great Firewall, has developed over two decades and is continually being refined.

Even virtual private networks, services that can mask users' locations and identities in order to help them jump the firewall, are hard to get for regular Chinese citizens.

While Russia's increasing internet controls will likely accelerate this push toward divergent internets, the country is far off from creating anything near the technical capability behind China's restrictions.

"It's taken years for the Chinese authorities to get where they are today. And their strategy has evolved and adapted during this time. Russia cannot do this overnight," said Charlie Smith, founder of GreatFire.org, an organization that monitors censorship in China.

Paul Triolo, senior vice president for China and technology policy lead at strategic advisory firm Albright Stonebridge Group, said that China's system allows "internet censors and internet controllers much more granular leeway to monitoring traffic, turn off geographical areas, including down to the block level in cities, and be very precise in their targeting of offending traffic or users."

That is something Russia cannot replicate, he added.

Holes in the Russian firewall

It is difficult for Chinese citizens to get around Beijing's tight internet controls. The government has regularly clamped down on VPN apps, which are the best option for evading the Great Firewall.

But Russians have been able to evade the Kremlin's attempts to censor the internet. VPNs have seen a surge in downloads from Russia.

Meanwhile, Twitter has launched a version of its website on Tor, a service that encrypts internet traffic to help mask the identity of users and prevent surveillance on them.

"Putin appears to have misjudged both the level of technical savvy of his citizens and their willingness to seek workarounds to continue to access non-official information, and the many new tools and services, plus workarounds and channels that have sprung up over the past five years that enable people who really want to maintain access to outside information channels to do so," Albright Stonebridge Group's Triolo said.

Will Chinese firms take advantage?

As U.S. and European firms suspend business in Russia, Chinese technology companies could look to take advantage of that. Many of them, from Alibaba to smartphone maker Realme, already have business there.

So far, Chinese companies have remained silent on the issue of the Russia-Ukraine war.

Beijing has refused to call Russia's war on Ukraine an "invasion" and has not joined the United States, European Union, Japan and others' sanctions against Moscow.

It's therefore a tricky path for Chinese corporates.

"So far there does not seem to be any guidance coming from central authorities in China on how companies should deal with the sanctions or export controls, so companies with a large footprint outside China are likely to be reluctant to buck restrictions," Triolo said.

"They will be very careful in determining both Beijing's wishes here, weighing how to handle demands from Russia customers old and new, and gauging the risks to their broader operations of continuing to cooperate with sanctioned end user organizations."

The Chinese are likely to make their moves depending on the tone from Beijing, according to Prakash.

"If Beijing continues to tacitly support Moscow, then Chinese tech firms have several opportunities. The biggest opportunity is for these companies to fill the gap that Western companies created when they exited Russia," he said. "The ability of these companies to grow their footprint and revenue in Russia is massive."

Lynk

Lynk