Should You Clap on the 1 and 3 Beats or the 2 and 4?

Listen to this clip of blues legend Taj Mahal playing a concert in Germany in the 1990s. The crowd is clapping along happily to “Blues with Feeling,” but Taj stops the performance mid-song.Read more...

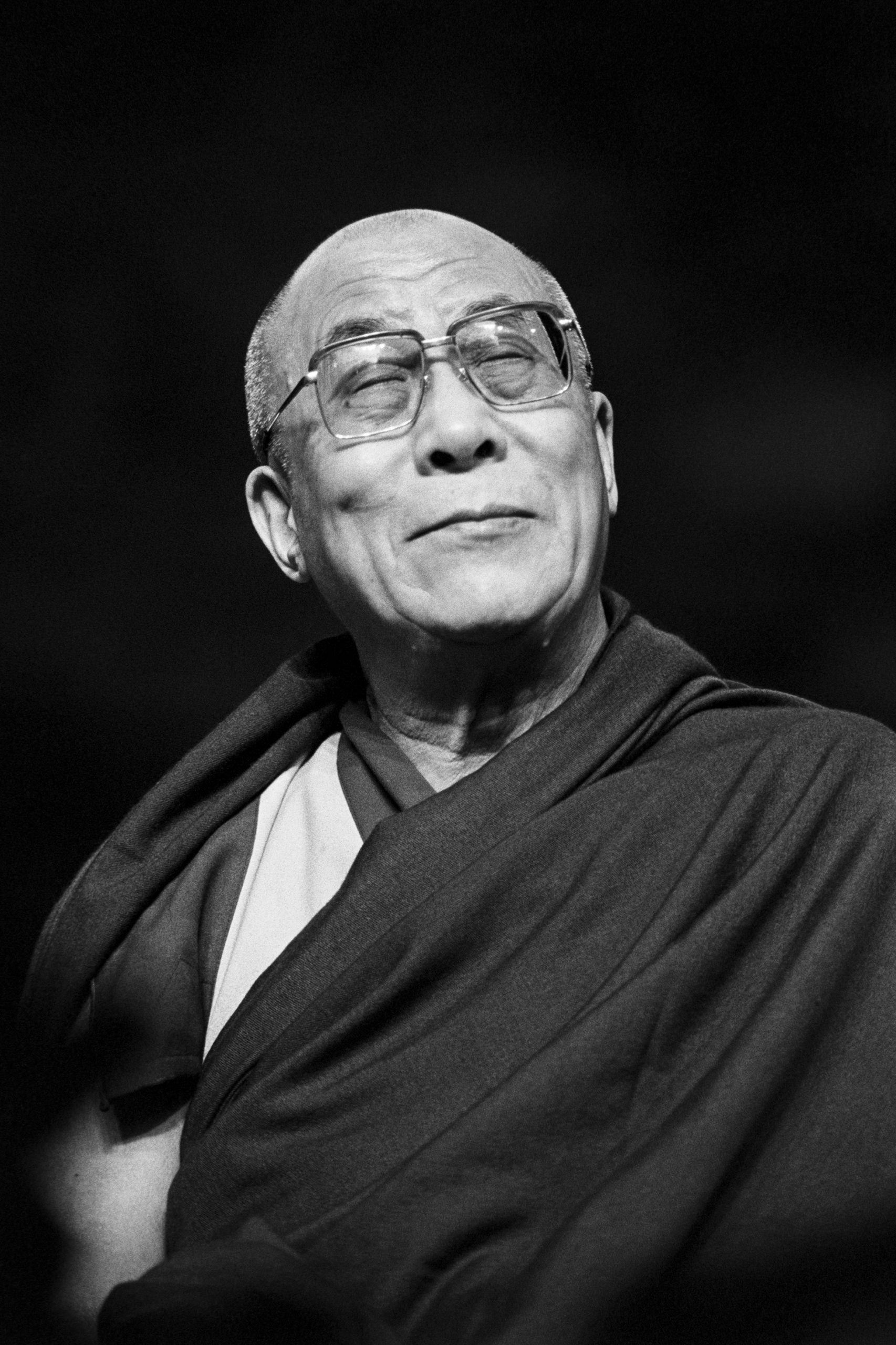

Photo: dwphotos (Shutterstock)

Listen to this clip of blues legend Taj Mahal playing a concert in Germany in the 1990s. The crowd is clapping along happily to “Blues with Feeling,” but Taj stops the performance mid-song.

“Wait, wait, wait,” Mahal says. “This is schwarze music.” Mahal explains that crowd’s beat might be right for Mozart, Chopin, and Tchaikovsky, but for his jazz/blues style, they should be clapping like, “one-TWO-three-FOUR.”

This got me thinking about clapping, snapping, tapping our feet, and otherwise rhythmically reacting to music, and whether there’s a right or wrong way to do it. It turns out to be a complicated question that touches on race, identity, and history. So a-one-and-a-two-and-a-way we go…

Rhythm and popular music

Most of the music most people enjoy is in 4/4 time. That’s four beats per measure—when you “count along,” you go “1, 2, 3, 4.” There’s the occasional 3/4 ballad, and oddballs like Radiohead and Rush will sometimes jam in 5/4 or 7/8 time, but those are outliers; most of us, mostly, listen to music in 4/4 time.

G/O Media may get a commission

When we are moved to physically respond to music, to clap or snap along, we often only clap on two beats each measure—either the 1 and the 3 or the 2 and 4—and which pair we “land on” while listening to which music can say a lot about who we are.

Like Taj Mahal said, emphasizing the first beat of a measure, the downbeat, is a hallmark of traditional Western music—think of the drum beat in marching band music or the “Oom” part of Oom-pah music. But music that comes down hard on the backbeat, the 2 and 4, is associated with historically subversive, grassroots musical forms like blues and jazz.

But audiences don’t always get it. Clapping at the “wrong” time, especially the 1 and 3, can get you yelled at by Justin Bieber, snarked on by George Collier, and force Harry Connick Jr. to add a beat to his piano solo just to make you less lame. But is it wrong?

“So, just clap on the 2 and 4?”

While “friends don’t let friends clap on the 1 and 3” might be a music-nerd meme, and someone might write a children’s book called Clap on the 2 and 4, there’s more to it than that.

Like, check out this clip of Frankie Lymon performing “Little Bitty Pretty One” in 1960. Ignore (if you can) the stilted reaction shots of the teenage music fans in the audience, and focus on when they clap. Lymon comes out clapping on the 2 and 4, and the groove is heavily built on the backbeat, but by the end of the song, the crowd is leaning into that 1 and 3 hard. I ran this clip by musicologist Alexandra Grabarchuk, to get some insight on what’s going on here.

“There’s a very clear turning point,” Grabarchuk said,“in the little humming intro that he does; it’s much more clear that there’s offbeat emphasis. But then, right when the regular drum beat comes in, the crowd starts clapping. At first they’re divided, then the majority wins out and they start clapping on the 1 and 3.”

So are the crowd “wrong” for clapping on the 1 and 3? Should Lymon have stopped the performance to yell at them ala Justin Bieber? Not necessarily.

“Musicologically speaking, you can find justification for clapping on the dominant beats or on the offbeats. I think it’s more of a sociological question, in terms of who actually does it when,” Grabarchuk said. “It seems to me very much like a group psychology question too…it has to do with cultural conditioning, some sort of group crowd psychology, and some sociological markers in terms of what kind of group you belong to and how that group interfaces with the music that they interface with.”

As much as some people might want it, there’s no hard and fast rule about which beat it’s better to clap on. According to Duke Ellington, “One never snaps one’s fingers on the beat. It’s considered aggressive,” but that’s within the context of jazz. (And it’s within the context of comical, performative hipness. Ellington goes on to say, “By rotating one’s finger-snapping and choreographing one’s earlobe tilting, one discovers one can become as cool as one wishes to be.”) In the context of other forms of music, it’s not as simple as Ellington’s statement—James Brown, Bootsy Collins, and just about every other funk musician are clearly proponents of “the one,” disco is about all four beats being equal, and rock music is all over the place.

I asked Frank Meyer, guitarist and vocalist for L.A. punk rock legends the Streetwalkin’ Cheetahs, about when people should clap at shows. “It all depends on the groove,” Meyer said. “The numbers mean nothing until the groove. It’s not about math, anyway.”

What your clapping says about you, your childhood, and American history

Most people, I assume, never think about any of this, and clap when they feel moved to in whatever way they want, but even if you don’t realize it, how you keep time is often coming from deep, cultural, and personal place.

According to Grabarchuk, if you don’t have musical training, the music you listen to as a child, and the reaction of the people around you to that music, likely determines whether you’re a “1-3 clapper” or a “2-4 clapper,” and that distinction often falls along racial lines in America.

“We are in some sense programmed by the people around us and by our culture and by the musical cultures we participate in, particularly at a young age,” Grabarchuk said. “If you’re singing hymns in church in as a white person in the midwest as a kid growing up, that really tends to emphasize stuff on those dominant beats of 1 and 3.”

“It becomes really complicated when 100, 200, or 1,000 people get together and are listening to something. They’re all going to be hearing a slightly different version of what’s actually happening, and they will all be responding physically in a different way. And this is where the group psychology question of ‘who’s going to dominate?’ comes in. Well, it’s probably going to be the racial class that generally ‘gets the floor,’ that generally gets the airtime, in a country that is built on ultimately white principles and the idea of white supremacy.”

“It’s like heteronormativity or patriarchy. All of these things seem sort of invisible, but really they’re always hovering around us, and making themselves known in who claps on what beat, and who claps louder than the other people.”

Astrong

Astrong