The Diamond Sutra

Timeless Buddhist wisdom The post The Diamond Sutra appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

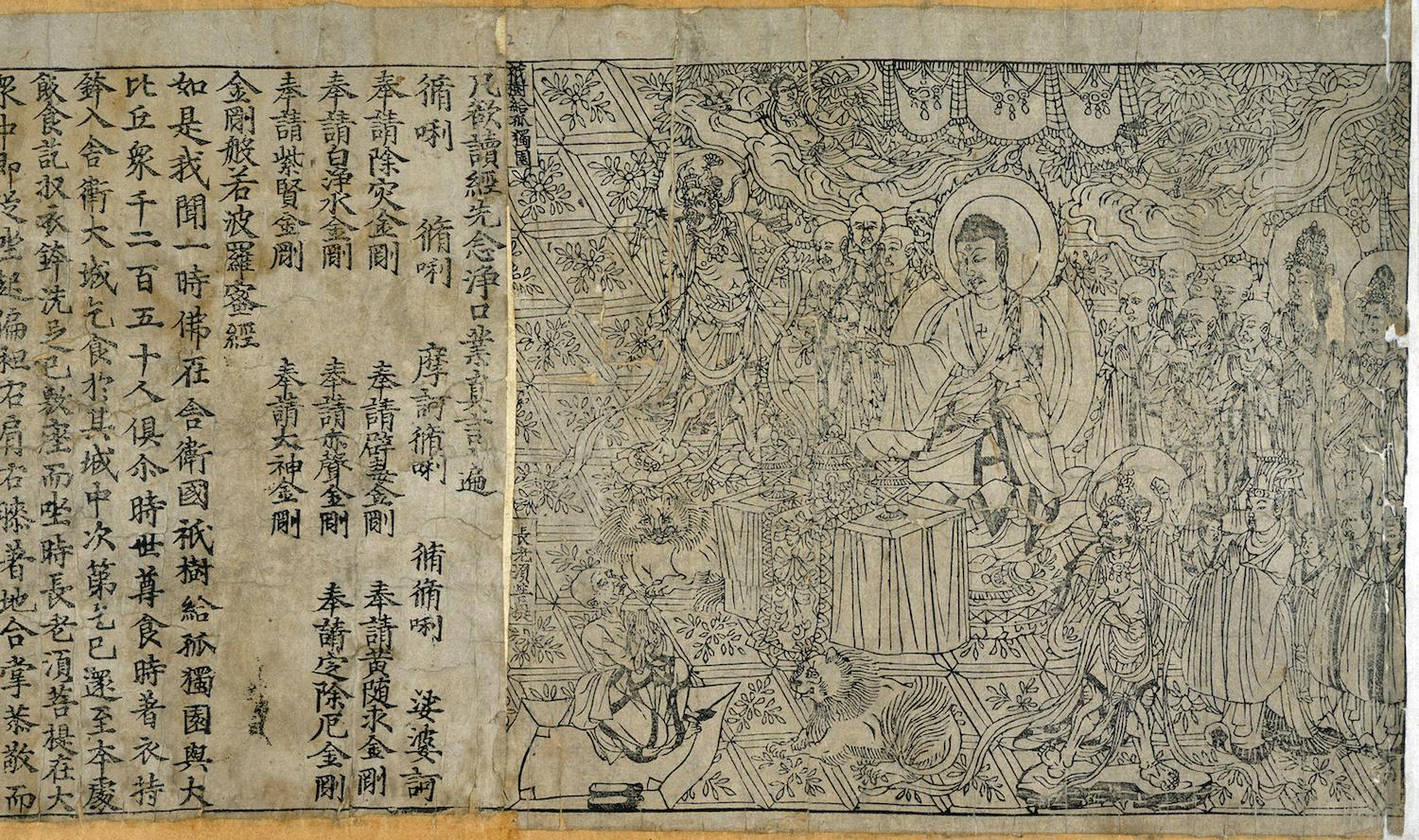

The Diamond-Cutter Perfection of Wisdom Sutra (Sanskrit: Vajracchedika-prajnaparamita Sutra), known in English as the Diamond Sutra, is one of the most revered Mahayana sutras and is considered a culmination of the Prajnaparamita (Perfection of Wisdom) collection of teachings. Written between the 2nd and 4th centuries CE and translated into Chinese in the early 5th century, the Diamond Sutra has influenced Buddhist thought and practice for over 1,500 years, captivating scholars, commentators, teachers, and serious practitioners alike.

Set in a great park with an assembly of laypeople, arhats, bodhisattvas, gods, demigods, and asuras, this sutra presents a dialogue between the Buddha and Subhuti, an arhat known for mastering loving-kindness. It explores the nature of reality, tearing down our usual perception of the world and exposing the underlying emptiness (sunyata) of all phenomena. Subhuti, moved to tears by its wisdom, immediately chooses ordination.

The whole sutra can be read in one sitting and is often chanted daily or weekly. This selection of passages represents the core themes of the Diamond Sutra, including a few of its most well-known sayings that Buddhists have long incorporated into ritual, expressed in art, and contemplated in practice.

After the first two sections set the scene, Section 3 delivers a powerful statement: “There are no sentient beings to be liberated and no self to attain perfect wisdom.” The rest of the sutra keeps circling back to this mind-bending idea. Section 6 offers the well-known raft metaphor, where even the sacred dharma is only a means to an end, meant to be left behind after crossing to the other shore. Section 10 contains another very famous gem: “A bodhisattva should develop a mind that functions freely, without depending on anything or any place.” In today’s world of constant distractions, this straightforward advice on nonattachment remains remarkably relevant.

Section 14 explains nondiscriminatory compassion, a key focus of the sutra. It teaches that genuine compassion is not selective or based on personal whims but selfless and sees beyond superficial differences. Section 32, the sutra’s poetic pinnacle, compares our experience of the world to dreams, bubbles, and flashes of lightning, emphasizing the fleeting, insubstantial nature of what we think is real. Enlightenment comes from insight into this eternal truth.

The Diamond Sutra is a living teaching that continues to challenge even the most astute practitioner. It pushes us to look beyond the surface, question our reality, and cultivate an awareness as clear and sharp as a diamond. Transcending time, space, and culture, this Mahayana teaching offers insights that can cut through the noise of modern life and shake up our perception of the world. Read it and experience its wisdom of profound emptiness slice through reality’s illusions.

Selections from the Diamond Sutra

Section 3

The Buddha said to Subhuti, “All the bodhisattva-mahasattvas, who undertake the practice of meditation, should cherish one thought only: ‘When I attain perfect wisdom, I will liberate all sentient beings in every realm of the universe, whether they be egg-born, womb-born, moisture-born, or miraculously born; those with form, those without form, those with perception, those without perception, and those with neither perception nor non-perception. So long as any form of being is conceived, I must allow it to pass into the eternal peace of nirvana, into that realm of nirvana that leaves nothing behind, and to attain final awakening.’

“And yet although immeasurable, innumerable, and unlimited beings have been liberated, truly no being has been liberated. Why? Because no bodhisattva who is a true bodhisattva entertains such concepts as a self, a person, a being, or a living soul. Thus there are no sentient beings to be liberated and no self to attain perfect wisdom.”

Section 6

Subhuti said to the Buddha, “World-Honored One, in times to come, will there be beings who, when they hear these teachings, have real faith and confidence in them?”

The Buddha: “Subhuti, do not utter such words. Five hundred years after the passing of the Tathagata, there will be beings who, having practiced rules of morality and being thus possessed of merit, happen to hear of these statements and will understand their truth. Such beings, you should know, have planted their root of merit not only under one, two, three, four, or five Buddhas, but under countless Buddhas. When such beings, upon hearing these statements, arouse even one moment of pure and clear confidence, the Tathagata will see them and recognize their immeasurable amount of merit. Why? Because all these beings are free from the idea of a self, a person, a being, or a living soul; they are free from the idea of a dharma as well as a no-dharma. Why? Because if they cherish the idea of a dharma, they are still attached to a self, a person, a being, or a living soul. If they cherish the idea of a no-dharma, they are attached to a self, a person, a being, or a living soul. Therefore, do not cherish the idea of a dharma nor that of a no-dharma.

For this reason, the Tathagata always preaches thus: ‘O you bhikshus, know that my teaching is to be likened unto a raft. Even a dharma is cast aside, much more a no-dharma.’ ”

Section 10

The Buddha asked Subhuti, “What do you think? When the Tathagata practiced in ancient times under Dipankara Buddha, did he attain any Dharma?”

“No, World-Honored One, he did not attain any Dharma while practicing with the Dipankara Buddha.”

“Subhuti, what do you think? Does a bodhisattva create any harmonious buddha fields?”

“No, World-Honored One, he does not. Why? Because to create a harmonious buddha field is not to create a harmonious buddha field, and therefore it is known as creating a harmonious buddha field.”

“So, Subhuti, all bodhisattvas should develop a pure, lucid mind that doesn’t depend upon sight, sound, touch, flavor, smell, or any thought that arises in it. A bodhisattva should develop a mind that functions freely, without depending on anything or any place.”

Section 14

Venerable Subhuti, listening to this discourse, through the shock of the Doctrine, had a deep understanding of the meaning of the sutra and was moved to tears. He said to the Buddha, “It is wonderful, indeed, World-Honored One, how well the Tathagata has taught this discourse on Dharma. Through it [a new level of] cognition has been produced in me. Never before have I heard such a discourse of Dharma. World-Honored One, if someone hears this sutra and has pure and clear confidence in it, that person will gain true perception. And what is called true perception is indeed no-perception. This is what the Tathagata teaches as true perception.

“World-Honored One, it is not difficult for me to have faith in, to understand, and to memorize this sutra, which I have just heard. But in the ages to come, in the next five hundred years, if there are beings who, listening to this sutra, are able to believe, understand, and memorize it, they will indeed be most wonderful beings. In them no perception of a self, a person, a being, or a living soul will take place. And why? Because that which is perception of self is no-perception. That which is perception of a being, a person, or a living soul is no-perception. And why? Because the Buddhas have left all perceptions behind.”

The Buddha said to Subhuti, “It is just as you say. If there is a person who, listening to this sutra, is not frightened, alarmed, or disturbed, you should know him as a wonderful person. Why? Because what the Tathagata has taught as prajnaparamita, the highest perfection, is not the highest perfection and is therefore called the highest perfection.

“Moreover, Subhuti, the teaching of the Tathagata on the perfection of patience is really no perfection and therefore it is the perfection of patience. Why? Subhuti, when, in ancient times, my body was cut to pieces by the king of Kalinga, I did not have the idea of a self, a person, a being, or a living soul. Why? When at that time my body was dismembered limb after limb, joint after joint, feelings of anger and ill will would have arisen in me had I had the idea of a self, a person, a being, or a living soul.

“With my superknowledge I recall that in my past five hundred lifetimes I have led the life of a sage devoted to patience and during those times I did not have the idea of an ego, a person, a being, or a soul.

“Therefore, Subhuti, a bodhisattva, detaching him- or herself from all ideas, should rouse the desire for utmost, supreme, and perfect awakening. He or she should produce thoughts that are unsupported by forms, sounds, smells, tastes, tangible objects, or mind objects, unsupported by Dharma, unsupported by no-Dharma, unsupported by everything. And why? Because all supports are no supports. This is the reason why the Buddha teaches that a bodhisattva should practice generosity without dwelling on form. Subhuti, the reason he practices generosity is to benefit all beings.

“The Tathagata teaches that all ideas are no-ideas and that all beings are no-beings. Subhuti, the Tathagata is one who speaks of things as they are, speaks what is true, and speaks in accordance with reality. He does not speak deceptively or to please people. Subhuti, in the Dharma attained by the Tathagata there is neither truth nor falsehood.

“Subhuti, if a bodhisattva should practice generosity while still depending on form, he or she is like someone walking in the dark. He or she will not see anything. But when a bodhisattva practices generosity without depending on form, he or she is like someone with good eyesight walking in the bright sunshine—he or she can see all shapes and colors.

“Subhuti, if in times to come the sons and daughters of good families memorize and recite this sutra, they will be seen and recognized by the Tathagata with his buddha knowledge, and they will all acquire immeasurable and infinite merit.”

Section 32

“Again, Subhuti, if a son or daughter of good family were to pile up the seven precious treasures in all the three thousand chiliocosms and give them away as a gift to the Tathagatas, the arhats, and the fully enlightened ones, and, on the other hand, if someone were to take but one stanza from this Vajracchedika Prajnaparamita and bear it in mind, teach it, recite and study it, and illuminate it in full detail for others, his or her merit would be much more immeasurable and incalculable [than that of the former]. And in what spirit would he or she illuminate it for others? Without being caught up in the appearances of things in themselves but understanding the nature of things just as they are. Why? Because:

So you should see [view] all of the fleeting world:

A star at dawn, a bubble in the stream;

A flash of lightning in a summer cloud;

A flickering lamp, a phantom, and a dream.

When the Buddha had finished [speaking], Venerable Subhuti, the monks and nuns, the pious lay men and women, the bodhisattvas, and the whole world with its gods, asuras, and gandharvas were filled with joy at the teaching, and, taking it to heart, they went their separate ways.

♦

Excerpted from The Diamond Sutra: Transforming the Way We Perceive the World by Mu Soeng, Wisdom Publications, 2000.

Fransebas

Fransebas