The Discipline of Compassion

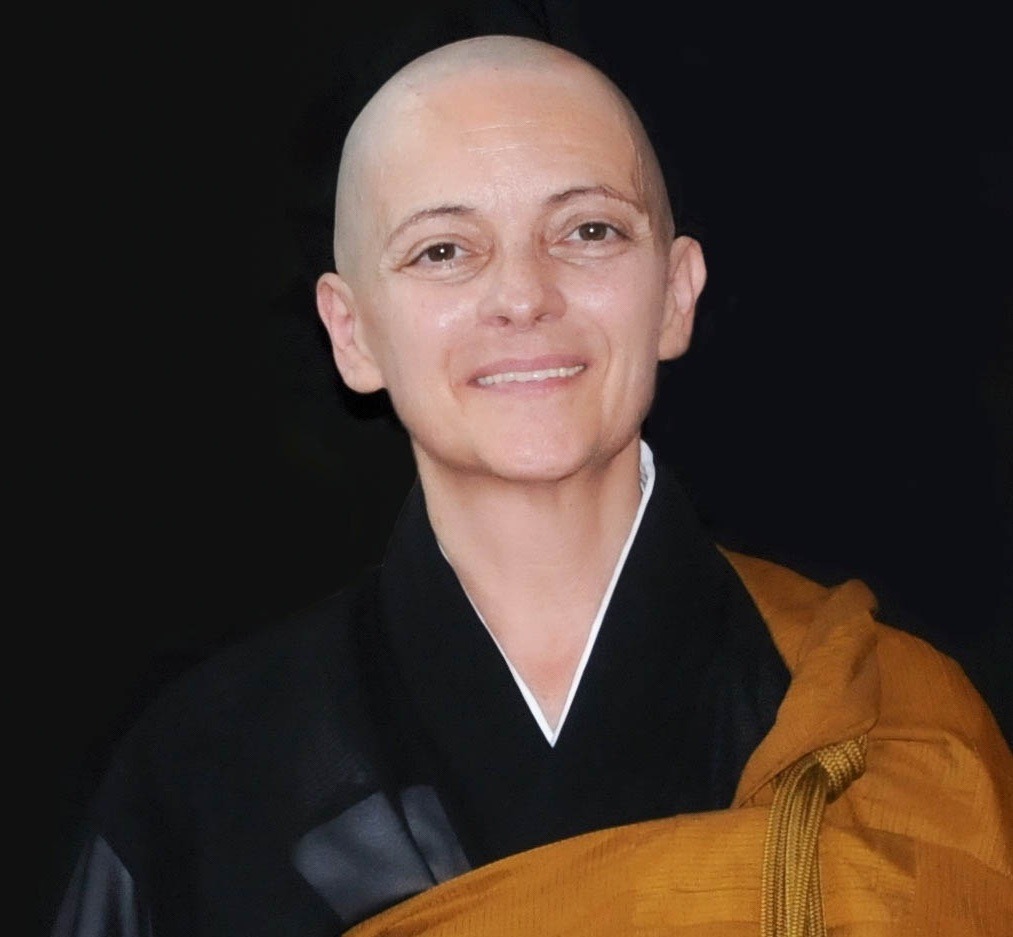

Zen teacher Anna Maria Shinnyo Marradi on mushotoku, women in Zen, and acting without self-interest The post The Discipline of Compassion appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

Florence is known for its Renaissance churches and marble saints, but on a quiet street near the Arno River stands another kind of temple—one built on discipline rather than stone. The Tempio Zen Shinnyoji, founded in 2004, is the first Italian temple recognized by the Japanese Soto Zen school. Its abbot, Anna Maria Shinnyo Marradi, trained in Japan under Tenrai Ryushin Azuma Roshi at Daijoji Monastery. Today, she is one of Europe’s few officially recognized fukyoshi, a missionary authorized to transmit the Soto Zen teachings abroad.

In this conversation, translated from Italian, Marradi reflects on women in practice, the meaning of mushotoku—“practice without profit”—and what it takes to cultivate compassion without sentimentality.

In many Zen groups, women are the majority of practitioners. Has being a woman teacher influenced your experience? In my temple, women are not the majority, but in general that’s true. I don’t really know how my being a woman plays out in my role as a teacher. What I do feel strongly is the need for women to connect—to form networks, to support one another.

Even before I entered the religious life, I experienced this imbalance. When I worked in business, I had to do ten times more than a man to receive the same recognition. It’s not so different in religious settings. In Japan, definitely; in Europe, it changes a little, but you’re still a woman. We need to make our worth visible—not to create a separate label, not to defend ourselves but to stand together, side by side. “Sisterhood” sounds artificial to me, but “sisters” doesn’t. Sisters in the dharma, in life, and in our challenges.

For someone new to Zen, what happens here when they sit zazen? What is the intention behind this practice? The intention should be shinjin datsuraku—“dropping off body and mind.”

When we sit, we don’t have to appear a certain way, prove anything, or confirm anything. We simply are. Sitting is about letting go of every defense and turning inward to touch our true nature—the light within.

But practice is never for oneself alone. We sit to return the fruits of practice to others. What we discover in meditation has meaning only when we bring it back into the world. Practice for personal well-being is fine, but unless it extends beyond the self, it remains incomplete. We sit not to appear, not to prove, not to achieve—but simply to be. Whatever blooms from that belongs to everyone.

Many people look outside themselves for answers—teachers, new traditions, another retreat. Why is it so hard to trust our own capacity for awakening? We’re not used to it. We expect constant confirmation from outside—a sign, a guru, a validation. Some people wander endlessly, the “vagabonds of the spirit,” moving from one center to another, always searching for someone to fix their life.

In Zen, faith means trust—not faith in a god who saves you but trust that you can walk the same path the Buddha walked. You verify it day by day: Your life improves, your gaze widens, your compassion deepens. The challenge is self-discipline. Sitting every day, facing yourself, is not easy. It takes courage to meet what you find—both the parts you like and the parts you don’t—and to accept them without condemnation.

The greatest fear is change. Knowing yourself changes how you see and act. You begin to move against the current—less shaped by trends or opinions—and yet more connected to others. That’s a paradox of practice: It individualizes and unites at once.

We sit to return the fruits of practice to others. What we discover in meditation has meaning only when we bring it back into the world.

Zen’s structure can look rigid—rituals, repetition, strict form. How can form lead to liberation? A form frees you from ego.

When you follow a form—bowing, walking, chanting—you move together, not according to personal impulse. In kinhin, the walking meditation, we lift our feet one after another, moving as a single breathing body. The practice becomes communal, not individualistic.

Even the temple’s sounds—the bell, the drum—are part of this. When you strike a bell with ego, the sound is harsh. When you meet it with attention, it rings true. You thank the instrument for serving its function, and in a way, it thanks you back.

Form is a discipline of respect, altruism, and the abandonment of a self-referential, egocentric vision. Through it, you enter into relationship—with others, with objects, with yourself.

You’ve spoken about mushotoku, the “spirit of no-profit.” What does that mean for you? It comes from nonattachment.

We live in a culture obsessed with goals and outcomes—even meditation is turned into performance. But Zen is “practice for the sake of practice.” You sit, and that’s all.

If you chase results, even subtle ones like “peace” or “realization,” you build another cage. The ego wants to attain; mushotoku means to stop bargaining with life.

It’s visible in small things. You let someone merge in traffic. They don’t thank you. You can feel offended—or you can say, “I did what felt right,” and move on. You act ethically without expecting a return.

If you always expect gratitude, you grow hard. You start thinking compassion is naive. But mushotoku isn’t naivete—it’s love without calculation.

The Buddha said each person must be their own teacher, yet Zen emphasizes lineage and transmission. How do those fit together? The Buddha said, “Be a lamp unto yourselves.” In Zen we say, “The master points to the moon; each must find their own moon.” But we can’t always see clearly alone. Ego is subtle, so guidance matters.

A master doesn’t save you—they accompany you. Finding a true teacher is rare, and trusting one even rarer. You have to choose carefully, then let go of control.

A teacher is human—fragile, imperfect. You respect the role but don’t build a pedestal. Trust and discernment must coexist.

You also speak of mushin, the “pure heart.” How do we keep that alive amid today’s uncertainty and conflict? In Japanese, shin means both heart and mind—there’s no separation. “Mu” means emptiness; therefore, “mushin” is a heart-mind that is empty—free from attachments and selfishness, and thus originally pure.

A pure heart is not emotionless. It’s a heart free from self-interest. Detachment doesn’t mean indifference; it means caring for others’ well-being without clinging.

To act with a pure heart is to feel the interconnection of all beings, to understand that what you do never concerns only you. It’s working on attachment, on ego, on insecurity—the roots of possession and self-assertion.

As we awaken, we lose the need to prove ourselves. We act more lightly, with humility. From that lightness comes clarity—the ability to respond appropriately, without premeditation or dogma.

Before we end, would you share a Zen story that you find meaningful? There’s one I often recall.

An elderly teacher cared for a young monk living in solitude. After ten years, she wondered what he had realized. She sent a young woman to test him. The woman embraced the monk and asked, “And now—what happens?”

The monk replied, “An old tree in winter—dry, unable to bloom.”

The teacher, hearing this, burned his hut. He had learned detachment but not compassion.

That story reminds me: Detachment without warmth is a misunderstanding. True freedom includes compassion; otherwise, it’s just another form of ice.

Tekef

Tekef