The List

A Buddhist reality check The post The List appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

Right after I was ordained, a friend, who isn’t Buddhist, said, “Wow—does this mean you’ll get to marry people?”

I said, “Maybe! Buddhists don’t have much to say about marriage. We tend to specialize in the other side.”

He said, “What other side?”

I said, “Death.”

Sure enough, I was back in Philadelphia for about a week when a friend texted. We hadn’t spoken in over a year. This friend might have heard the news of my recent ordination. He asked if I’d be willing to pray for him. He had colon cancer.

I agreed, and added my buddy’s name to a Post-it I keep by my shrine. It’s a list, with Name, sickness.

Buddhism has a lot to say about death. One of our refrains is: “Birth, old age, sickness, death.” In Thai this is (transliterated): “guht-gah-jep-tai.” There’s an end-stopped monosyllabic practicality to the phrase. I heard it a lot growing up. You’d share your tale of woe, or hear someone else’s, and it isn’t that the suffering wasn’t met with sympathy—it was. Thai people are generally some of the kindest folks you’ll meet. But after the outpouring, someone would inevitably say, “guht-gah-jep-tai,” with a shrug, as in—what are you going to do?

This is Buddhist reality. It’s meant to be a reminder. Birth, old age, sickness, death. This is the arc of our life.

I know this dose of reality can sound like a downer. So dour! Who would want to dwell on it? But it could also come as a relief. Maybe you thought it was just you, suffering away alone. Maybe your aches, your pains—you were taking it personally. When someone says guht-gah-jep-tai with that sympathetic half shrug, you can exhale. Oh yeah! We are all subject to this arc.

***

It’s not new to say that Western culture spends an extraordinary amount of energy denying death. This looks like plastic surgery. This looks like self-loathing and shame as we age, particularly for those of us in the female body. This looks like our elders being hidden away and unvisited, because we do not want to be reminded of our own mortality. This looks like prolonged medical interventions exhausting a family, causing more pain to the patient, running up insurance bills, and plummeting a clan off the cliff of denial.

Denial is hard work. It takes a lot of energy. It’s a kind of negative awareness, because it has to be kept up all the time. There is so much living we could do with that energy instead.

***

Growing up in Thailand, death was more present in the cultural ether. When my brother and I were kids, as we would buckle our seat belts, our mother would turn around from the driver’s seat and ask, “What do we think of?”

And we’d answer, “the Buddha!” in our piping little voices.

She meant—what do we think of when we die? My mom had been in a car accident a few years back. She tied death mind training, something we did quite a lot in Bangkok, to buckling seat belts. If we swerved, if it should be our day to die, she wanted her babies not to tighten in anguish, not to cry in fear, but—somehow—to think of the Buddha.

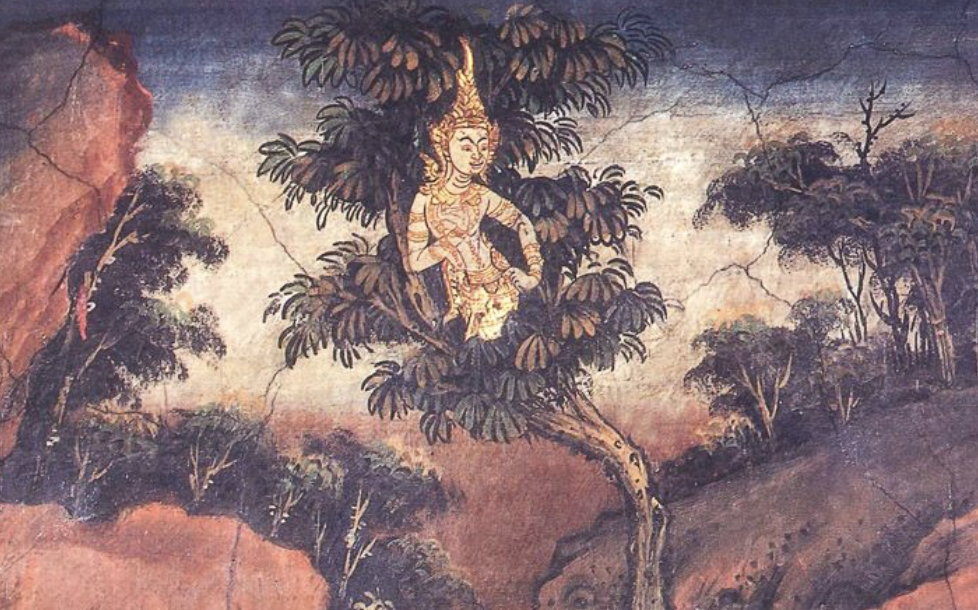

And not just any Buddha. Specificity matters. Mom has a great love for the Phitsanulok Buddha, with the elaborate golden headdress. We were to picture that Buddha, and take a better rebirth.

***

When my great-grandfather died, I was in my early 20s. At the funeral, his coffin was at the top of these huge steps. As the eldest grandchild, I helped my grandmother up the stairs. I gave her my arm so she could lean into me as she stood with her bad knees next to her siblings, surrounding the remains of their father.

Ah Lao Gong’s coffin was a flimsy particleboard box. It rested on a dais in front of the crematorium, which was throwing off a spectacular amount of heat. There was a small metal window to the fire. Two young monks leaned forward. I thought they were going to open the cremation window, but they tugged back the lid of the coffin. I saw liquid, solid, swirling white moving maggots. The smell was enormous. This was after nine days of monks chanting over my great-grandfather in tropical heat. The family sprang away. I clamped my teeth into my lips so I wouldn’t throw up. I gripped my grandmother’s elbow as she stumbled. Then the lid was back on, the window opened, and the coffin slid into the flames.

Can we make contact with the truth that we’re going to die?

We hadn’t known that was going to happen. I believe this practice of showing the body still occurs in working-class temples in Bangkok and in the countryside. The idea is to see the body and cut the attachment. Use someone’s death as an opportunity for the people alive.

There is a visceral realization that happens when you see the decomposing body of someone you love. You get that the body does not house that person anymore. You know, in the most intimate, unforgettable way, that you, too, will die.

***

Can we make contact with the truth that we’re going to die?

Some of us have already had near-death experiences. Some of us were very sick when we were young. Some of us are sick now. Let me invite you to close your eyes, right now, and breathe. Call up a scenario in which you die.

It might be a rainy night on Lincoln Drive in northwest Philly. You know the road. You take a turn. It’s all potholes and cars driving too fast. Tonight there are headlights shining through your wipers. Your mind shouts no-no-no-no. Horns. You think of your kids. You grip the wheel.

Now relax. Breathe.

Relax your mind again.

You’re dying. Congratulations! You’ve made it to the only date that is guaranteed.

Breathe.

***

The human life we’re currently engaged in is actually a mere stroll. We do our best to forget this, to deny our short-term span. The idea with Buddhist death practices is for them to be shocking so that death is not as shocking. They’re meant to be scary so that death is not as scary.

We call this mind training. You introduce the knowledge of death not intellectually but in the bodily sense, so that when your own death comes, your body automatically says, Hey! Wow. I’m here!

We don’t have to suffer over our death. We don’t have to try to cheat it. (Good luck with that.) We can greet it as punctuation. It’s like—Up and over the ridge! I wonder what will happen next?

Tibetan Buddhists tend to treat death as an opportunity. If you can transcend your fear of death, it’s probably because you have loosened your grip on self. If you have loosened your grip on self, as Anam Thubten says, “no self, no problem.” There isn’t anguish over your departure, which can cause heavy karma to cling to your consciousness.

Buddhists say that if you meditate on death four times a day, you will be fully present in life. Imagine this as four bells that you ring throughout your day. Even if you cast your mind to your death only fleetingly, for seconds each time, it can help.

With your eye on such a horizon, who cares that your kid lost your favorite earrings? Who cares that your partner didn’t do the dishes? The practice is not nihilism. Living with death on your mind allows you to shower your family with love. You live with the sense of awe and wonder befitting our time on earth. You relish life. You’re in the zest of it.

***

Back to the list. If you have a meditation practice, I encourage you to keep a Post-it by your shrine. Name, sickness.

We can keep company with the dying. We can send love as they transition. The list can be full of real people you know. It can also have real people you haven’t met.

Child in a tent, Gaza.

Hostage in a tunnel, Israel.

So many people die in anguish, thinking they are utterly alone. We can witness them and hold them in our hearts. We say, You’re doing the great event promised to all of us. Go in peace.

If you chant the four immeasurables, send that to your list. When you dedicate your practice, send that to your list.

This will have benefit for you as well. It will help you remember death. It will expand your awakened heart, bodhicitta. And it will help the dying transition.

♦

This piece was originally published on Sunisa Manning’s Substack, Dharma Bites.

Aliver

Aliver