The Middle Way of Sobriety

Reflections on non-intoxication The post The Middle Way of Sobriety appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

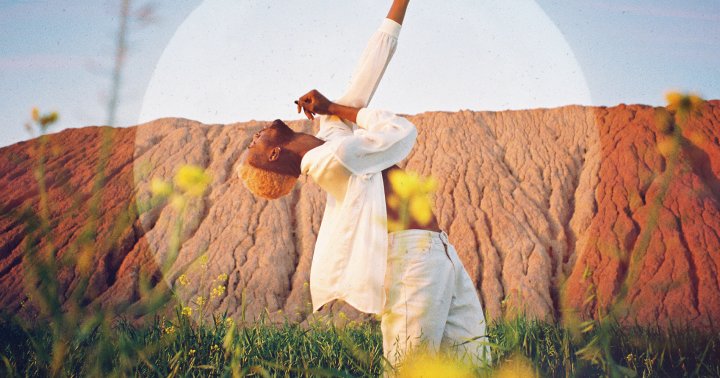

Photo by Roberto Carlos Roman Don | https://tricy.cl/3xBqBII

Photo by Roberto Carlos Roman Don | https://tricy.cl/3xBqBIIMost people think of sobriety as being free of alcohol—and they’re right. But the practice and principle of sobriety can go much deeper than that. Sobriety means not hiding. Sobriety is to develop your own capacity to face yourself as you are—in all your vulnerability, pain, or anxiety. Most deeply, it can mean facing the impermanent nature of all of our states of being and the very limited control we have over what happens in our lives or comes up in our bodies and minds. It’s to cultivate resilience in the face of reality.

In June 2017, my mother died of alcoholism. To be more specific, she died from alcohol withdrawal symptoms after a weeks-long binge. Though she had been doing better—down to a maintenance level of drinking for about a year—alcohol was her most persistent and destructive addiction. She died just weeks before my friend, the dharma and yoga teacher Michael Stone, passed away after ingesting fatal street drugs in an attempt to treat the discomfort of a psychiatric disorder.

These deaths made me consider my own vulnerability to alcohol abuse. Alcohol, in particular, is a family affliction on my mother’s side. I have never been addicted to alcohol or a binge drinker, but later in life, after a fairly sober youth, social drinking among my aging peers led to drinking once or twice a week. After my mother died, now possessing a sharpened sense of caution, I began to notice alcohol’s negative effects on me, especially when I drank for two or three days in a row or used alcohol as a nightcap before bed. Since then, although I slip from time to time, I’ve come to realize that alcohol is not my friend. It’s a relationship better not cultivated.

I was recently led to reflect on this when I read an essay by the Zen teacher Tenshin Reb Anderson, from his book Being Upright, on the traditional Zen commitment—honored by some more in the breach than the observance—not to use intoxicants.

Anderson points out that the practice of non-intoxication is broader than not using alcohol or drugs. On a deeper level, it is a choice to not escape from how things are in this moment. It’s a principle that encourages facing, not manipulating, your own state of being. This principle is in direct opposition to one of the great preoccupations of our time: self-medication.

The urge to self-medicate is understandable, especially given everything that has happened in recent years. I still remember the flurry of tweets on election night 2016 referencing the whisky bottles that were soon to be picked up. Then there’s the pandemic: since COVID-19 hit in earnest last March, alcohol sales have increased dramatically in many countries. It’s been a banner year for what Kurt Vonnegut, in Breakfast of Champions, called softening the brain with yeast excrement.

In British Columbia, where I live, beer and alcohol sales have risen between 8 percent in some places and 40 percent in others throughout the last year, and one study in the US found a 54 percent increase in March 2020 compared to the same week in March 2019. When you consider the associated dangers of drinking—domestic violence, car crashes, violent crime, addiction, heightened rates of cancer, and other diseases—the alcohol-fueled flight from the reality of 2020 may be one of the most damaging legacies of the pandemic. Self-medication in the form of alcohol, then, comes at a price—one that is known but too broadly ignored.

This seems a good time for a confession before I go on: other than the time I spent as a monk, I’m not much of a rule guy. I regard the five precepts as very sound ethical guidance, and though I respect those who follow them unswervingly, I don’t regard them as obligatory commitments in that way. Not that I break them willy-nilly either, that’s just not the shape of my practice. That’s to address the elephant in the room: Why are we even discussing this when the Buddha said not to drink, period? The reason is that I and many Buddhists in the West that I know, living in a culture pervaded by recreational drinking—and not being that inclined to follow rules—do in fact sometimes drink.

As for myself, when I do choose alcohol it’s usually for one of two reasons: sometimes it’s to relax and play with others, which is most often harmless, unless the chemistry backfires and leads to just being stupid or ill-tempered. More rarely, and in a way I consider more sinister, I drink to achieve what I call “the blackboard effect.” This phrase comes from Stephen King’s The Shining and its sequel, Doctor Sleep. The hero of the first book, Danny Torrance, who becomes an alcoholic like his father in the second, thinks to himself, “The mind was the blackboard. Booze was the eraser.” I’d modify that quote to include the body: the tensions, and knots of both body and mind are eased and then rendered beyond sensibility by alcohol. With alcohol, first you feel better, then you don’t feel at all (or you just feel sick).

Meditation, I would say, offers a more wholesome analog to the “blackboard effect.” When meditating, thoughts gently calm, tensions ease, and stories that imprison the mind become see-through or entirely stop—for a time. When you return mindfully to engage with the world there is a sense of rebirth, the very opposite in tone and effect to a hangover.

Of course, that’s not how we experience meditation at the start. Our first months of sitting may include experiences of relaxation, peace, or freedom, but for most people it also includes many hours of learning to deal with tumultuous thoughts, physical discomfort or pain, the unveiling of buried traumas or difficult emotions, and other varieties of unpleasant experiences we’d rather hide from. In other words it involves becoming more vulnerable. The fact is that developing a meditation practice that can be a real refuge for us involves a willingness to be sober. In that sense it functions exactly opposite to the M.O. of alcohol: meditation, though at first painful, develops our capacity to face our lives and be comfortable inhabiting them as they are. Alcohol offers immediate release at the price of coming back from the buzz with less capacity to live in our bodies, minds, and lives as they are.

***

What are we to make, though, of Buddhist teachers who have abused alcohol? In the Zen world, for example, Taizan Maezumi Roshi, Joshu Sasaki Roshi, and Soen Nagakawa Roshi come to mind. How could it be that these people who spent so much time in zazen, in sesshin, deconstructing the ego and heightening awareness, were so prone to escaping themselves in drink?

Was it the pressure of the position? Or was it, as Chogyam Trungpa, another famous Buddhist drunk, said, that true spiritual practice doesn’t cause less sensitivity to life but more? The claim I made above, that meditation gets easier, is true, and yet the path of a meditator can throw up surprises even after decades of practice. We sometimes underestimate how uncomfortable it can be to honestly face what the Buddha called the three marks of reality: the impermanent, unreliable, and uncontrollable nature of everything. In our rush to spread the dharma some of us neglect to point out that the path of the meditator has dark nights, lonely valleys, and its share of lions, tigers, and bears.

Do some Buddhists take to drink, in contravention of the Buddha’s own clear advice, because of the stress and destabilization that facing reality nakedly on the meditation seat can bring, or because of the pain of facing emotional challenges or a lack of control over what’s coming up for us even after substantial experience of practice?

I think this is possible. In my own experience, I’ve found that the very pursuit of what Reb Anderson calls sobriety can be a dangerous dance. Facing the reality of life can leave us raw, vulnerable, emotionally reactive, and lonely. Buddhist art and literature so often projects images of imperturbable wisdom and transcendent calm, and I suspect these images may at times exacerbate the pain of our vulnerable, chaotic existential condition. It may be helpful for Buddhist practitioners if we made it a habit of speaking more about our rough edges and human foibles, about our mundane, unpolished, or even just silly selves.

Maybe it’s time to talk more about how we masturbate as well as meditate, or about how automated, reactive and nonsensical the thoughts and impulses that still arise in the mind of long-term yogins, rinpoches, and roshis can be. That honesty is a form of sobriety too, one that might help free us from the need for escapism, whether it takes the form of substance abuse or fantasies about superhuman awakening. Hiding in idealized images of ourselves or others can be another form of intoxication which prevents us from understanding reality.

Maybe a willingness to be more vulnerable to others about our struggles—regardless of whether we are “teachers” or “students”—would ease our isolation and self-judgement. Maybe dropping idealistic fantasies in favor of an embrace of the real messiness of the spiritual path would help us to have less to run from. That might free us up to benefit from meditation without the dark nights of the meditative life becoming a new reason to hide in intoxication.

Cultivating Sobriety

I’ve found some progress on the path of my own sobriety in two ways. The first is what author James Clear calls an “atomic habit.” This entails not taking on the foolish and almost definitely impossible commitment of entirely refraining from any kind of intoxicant, whether its alcohol, food or what have you. For many of us such Cold Turkey will be followed by its sibling, Crash and Burn.

Instead I begin with noticing the urge to self-medicate and gently checking in to see if I can face what I want to flee from instead. I am sitting at my desk working and I have the urge to eat a snack I don’t really need. I want to change my brain chemistry—my stomach doesn’t need it. Or I’m getting ready for sleep and still keyed up from the stress of finishing the day’s tasks, putting my son to bed, having a thorny conversation with my wife about some decision we need to make. I feel like having a spiced rum and reading some poetry.

In both these cases if I take the intoxicant—the un-needed snack or the alcohol—I am avoiding facing my condition as it is. Yet there is another way. I find if I sit quietly for a moment, don’t run, let my mind and body settle in meditation, then the urge loses its pang. Oftentimes the discomfort underlying it disappears as well.

Sometimes this is surprisingly easy. When the habit of avoidance is absent, uncomfortable feelings are often shown to be tolerable, and when experienced mindfully without fear or aversion, they may dissipate, showing themselves to be, in the words of a Tibetan Buddhist teaching, paper tigers. [Caveat emptor: if you’re struggling with serious chemical dependency or high-risk substance abuse, it is best to consult a mental health professional, and the same goes for when disturbing thoughts are truly troubling and repetitive.]

***

Sometimes, though, we may choose self-medication or distraction regardless of our ideals. We are only human after all. I wouldn’t go so far as to recommend actual alcohol use—for fear of arousing the Buddha’s deathless ire. (Just kidding.) But if we’re honest about the fact that we are choosing to self-medicate or escape, then perhaps we can do so in a way which is, well, medicinal, or at least not overtly harmful. When I’m honest with myself that I am self-medicating, I can do so with some discernment. It becomes easier to choose a funny movie or a pizza rather than a beer.

As Reb Anderson points out, there is a lot of virtue to be found in spending time working with our experience as it is rather than just running from it. Isn’t that the essence of the Buddhist way? There are seasons for everything, but only the courage to explore things as they are—in all of their messiness, pain, and resistance to our desires—leads to real surprises. One of them might be our own freedom, waiting all the time right there and closer than we thought.

Get Daily Dharma in your email

Start your day with a fresh perspective

Explore timeless teachings through modern methods.

With Stephen Batchelor, Sharon Salzberg, Andrew Olendzki, and more

![]()

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.

This article is only for Subscribers!

Subscribe now to read this article and get immediate access to everything else.

Already a subscriber? Log in.

UsenB

UsenB

.jpg&h=630&w=1200&q=100&v=6e07dc5773&c=1)