Tibetan Mustang: The High Stakes and Living Practice of Monastery Maintenance

A new photography book sheds light on conservation efforts in the hidden kingdom. The post Tibetan Mustang: The High Stakes and Living Practice of Monastery Maintenance appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

Carrying cables and Diva-Lites, landscape photographer Kenneth Parker takes another step up the mountain. He’s no stranger to demanding treks, having previously braved the glaciers of Patagonia and the jungles of Laos and Myanmar, but this 100-mile journey through the Himalayas takes the cake. At close to 13,000 feet above sea level, the hillsides are dusty and treacherous, the air freezing and increasingly devoid of oxygen. Yesterday, he slept in a tent. Tonight, among the livestock.

Parker is on his way to Lo Manthang, the fortress-like capital of Upper Mustang, to check out the work of conservator Luigi Fieni. Nestled between Dhaulagiri, the seventh-highest mountain in the world, and Annapurna, the tenth highest, Mustang’s history dates back to 1380 AD. The so-called “Last Forbidden Kingdom,” today part of Nepal, rose to prominence as a nexus for trans-Himalayan trade between Tibet, Nepal, India, and China. This trade not only brought the kingdom earthly riches but also heavenly wisdom. Inviting gurus from both sides of the mountain range, Mustangi rulers turned their domain into a haven of Tibetan Buddhism. They translated Sanskrit texts and built monasteries, two of which, the Tubchen and Jampa temples, Fieni was put in charge of renovating.

“The short answer is karma,” Fieni says when asked what led him to Lo Manthang. Born in Italy, he briefly studied engineering before joining one of the country’s first conservation programs in Rome. There, one of his professors asked him to participate in an exciting and unprecedented project. Mustang, long inaccessible for a variety of reasons—including local resistance efforts against the Chinese occupation of Western regions of Tibet as well as a self-imposed tourist cap meant to preserve the region’s culture—had just opened up to the outside world. One of many projects taken on by Mustang’s last king—Jigme Dorje Palbar Bista, who abdicated by order of the Nepalese government in 2008—was to work with the American Himalayan Foundation in an effort to restore many of the damaged temples. Specifically, Tubchen and Jampa, which had fallen into disrepair over the last few centuries, threatening the survival of the unique culture they represented.

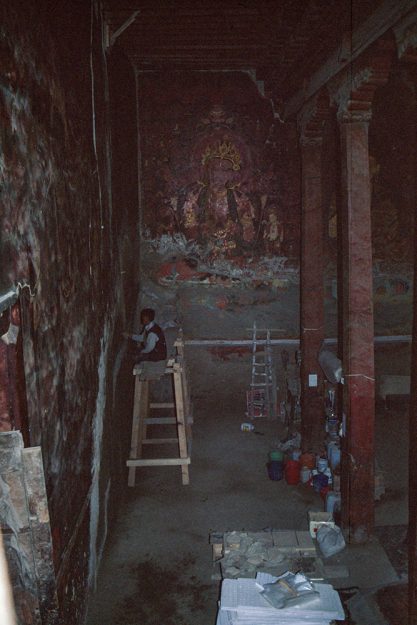

Leveling plaster on the east wall of Tubchen monastery. Image by Luigi Fieni.

Leveling plaster on the east wall of Tubchen monastery. Image by Luigi Fieni.Tibetan Buddhism is a Vajrayana lineage and includes four sub-schools–Nyingma, Kagyu, Sakya, and Gelug. These sects have a lot in common with other Buddhist traditions and the broader Buddhist landscape, including the core beliefs of reincarnation, the principle of nonviolence against all living beings, the role of meditation as a means of reaching enlightenment, as well as the commitment to the Buddha’s Four Noble Truths.

A key feature of Tibetan Buddhism—as well as other Mahayana Buddhist traditions—is reverence for bodhisattvas, spiritual practitioners who are close to achieving enlightenment but, instead, delay its ultimate attainment to guide others along the path to Buddhahood. Where a Buddha, having extinguished the flame of their being, disappears from the world, bodhisattvas, like the various tulkus, continue to be reborn for the benefit of all beings. Instead of devoting themselves to a single Buddha, Tibetan Buddhists worship a large pantheon of buddhas. The faded wall paintings in Tubchen and Jampa depict this universe, a complex hierarchy of demons, deities, and demigods.

Studying the techniques and materials employed by the paintings’ original creators, Fieni’s team has spent more than two decades restoring the work to the best of their ability. The art’s distinct visual style, a combination of regional influences, reflects the history of Mustang itself. Pigments made from gold and lapis lazuli, a precious stone mined in Afghanistan, are a testament to the medieval kingdom’s wealth and worldly connections, while intricate mandala designs hint at an equally impressive order of artistry and craftsmanship. According to an article from the Journal of Tibetology by Chen Ping-Yang, small details in the depictions of Buddhas and bodhisattvas—short necks, bowed eyes, elongated ears, and heart-shaped heads—betray influence from (and contact with) Nepal, China, and other old Himalayan kingdoms like Guge.

Because Tibetan Buddhism is largely an oral tradition—one of the sub-schools, the Kagyu, literally means “lineage by mouth”—the preservation of wall paintings is crucial to helping scholars better understand its teachings. As with art produced by other world religions, these paintings are not merely decorative but also function as illustrations of ideas and emotions that cannot easily be conveyed through words. The Mustangi painters used size to delineate the importance of figures, with the most important ones taking up the largest parts of the image. This reflects Tibetan Buddhism’s emphasis on strong leadership; where other forms of Buddhism diminish the position of the teacher, like the Theravada belief that nirvana can be found in and reached only by the individual, in Tibet, gurus living and dead are worshipped as gods. As stated in a preface to sayings from the 9th Karmapa Lama, the head of the Kagyu:

Guru-devotion involves both your thoughts and actions. The most important thing is to develop the total conviction that your Guru is a Buddha… If you doubt your Guru’s competence and ability to guide you, your practices will be extremely unstable and you will be unable to make any concrete progress.

Depictions of deities stress the attributes that mark their divinity. Akshobhya, one of the Five Wisdom Buddhas and ruler of the Eastern Pure Land Abhirati, can be recognized by his blue skin and vajra scepter, a ritualistic weapon that symbolizes both indestructibility and irresistible power. The embodiment of “mirror knowledge,” Akshobhya is thought to bestow wisdom by refining one’s perception of reality. In the book Tibetan Mustang, cowritten with Parker, Fieni writes, “Whether a red rose or a bloody dagger, a mirror reflects both simply as they are—without judgment to otherwise distinguish between the two reds by attempting to hold the first, or flee from the second. The mirror stands imperturbable and immutable, exactly as we should, regardless of how we may otherwise perceive the circumstances as favorable or unfavorable.”

For residents of Lo Manthang, the murals are not only historical artifacts but also objects of active worship—a duality that cannot and should not be ignored.

Sections of the Tubchen and Jampa wall paintings that had faded beyond recognition, and were therefore impossible to restore, were covered with new images selected by the Sakya Trizin, head of the Sakya school, and his son. Conservators originally met with the Sakya Trizin in India to help them identify some of the smaller figures on the murals, and later brought him to Lo Manthang to create a list of figures and stories that could be represented on the remaining space. The unorthodox decision was met with criticism by the conservation community, with Christian Luczanits, a professor of art and archaeology at the University of London, arguing that the new images obscured “many iconographic details that were still visible before repainting.”

Left: The Buddha above the entrance door before restoration. Right: The Buddha above the entrance door after restoration. Images by Luigi Fieni.

Left: The Buddha above the entrance door before restoration. Right: The Buddha above the entrance door after restoration. Images by Luigi Fieni.In Tibetan Mustang, Fieni draws up a similarly passionate defense, arguing that Western standards of conservation—derived from the study of “dead cultures” like ancient Rome and Egypt—cannot be applied to places like Upper Mustang, where age-old ways of life have carried into the present. For residents of Lo Manthang, the murals are not only historical artifacts but also objects of active worship—a duality that cannot and should not be ignored. Fieni later told Tricycle over Zoom:

“When I was working in Italy, I visited a small church with an old painting of St. Francis, which was missing a hand. The priest would ask us to fix it. ‘Come on,’ he said, ‘can’t you put a finger on there? You will leave St. Francis without a finger?’ In Europe, laws are strict. Nepal is not as regulated, and there was room for local people to do what they wanted, even if it took us a while to understand what that was. At first, I tried telling them what I had been told at school: that, in the end, the artist was more important than God. For people who believe, this is not the case. The monks asked again: ‘we want to pray, but we can’t if images are missing.’”

The importance of these images goes beyond symbolism. In Tibetan Buddhism, they also play a practical role regarding meditation. For Mustangi monks, the path to enlightenment isn’t hidden but laid out through an explicit system of rites and rituals. At various stages of their training, individuals are told to identify with the figures of the murals. “[This] imagery is intended to inspire the individual not only to seek eventual enlightenment, but to look beyond the self in the here-and-now in order to identify with the entire universe and to extend enlightened principles into the thoughts and actions of daily life,” says Kagyu Droden Kunchab’s Tamara Wasserman Hill. To leave the paintings incomplete is to make practice more difficult or nearly impossible.

Fieni’s time in Upper Mustang, which came to an end in 2019 when the Nepali government refused to renew his entry permit, was an intellectual as well as spiritual experience. Raised Catholic, he has since incorporated Buddhism into his worldview. “The truth has many doors, so that people can access it from different places,” he says. “In the end, it is not a matter of who is right and wrong, but of accepting different choices because they relate to different cultures. Since there can never be a globalization of conservation, we must be open-minded and let other people proceed the way they feel is best for them.”

Cliffs, Buckwheat Blossoms, Dhakmar-Meh; Mustang, Tibetan Plateau. Image by Kenneth Parker.

Cliffs, Buckwheat Blossoms, Dhakmar-Meh; Mustang, Tibetan Plateau. Image by Kenneth Parker.Life in Lo Manthang was tough. There was no electricity, running water, or cell reception, with high altitude turning even the most mundane of tasks into demanding exercise. “The scaffolding in the monasteries was three stories tall. If you forgot a brush, you had to go all the way up and down again. I lost a lot of weight—10 or 20 kilos per summer.” But life was also simple, with happiness stemming from things that, back at home, are too often taken for granted: a warm bed, the odd tourist sharing their prosciutto or Swiss cheese, or not getting picked to clean the Porta-Potty at the end of the work. “The less you have, the happier you are.”

Parker concurs. During his many travels in East Asia, the photographer quickly discovered a connection between his spirituality to his profession. “No mud, no lotus,” he tells Tricycle, recounting the hardship of his Himalayan trek. “The worse the weather, the better the picture.” Just as a seasoned Buddhist learns not to desire desirelessness, so does Parker wait for photographs to come to him—sometimes for hours on end.

“There are no doctrines or words,” he says of Buddhism, “nothing that you’re required to believe. It’s about directly pointing, without any intermediary words or ideas, and becoming a better observer.”

Tibetan Mustang: A Cultural Renaissance by Luigi Fieni and Kenneth Parker. Hirmer Publishers. Copyright © 2023. Images used with permission by Fieni and Parker.

ShanonG

ShanonG