To Be or Not to Be

How do we live with this outrageous fortune? The post To Be or Not to Be appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

How do we live with this outrageous fortune?

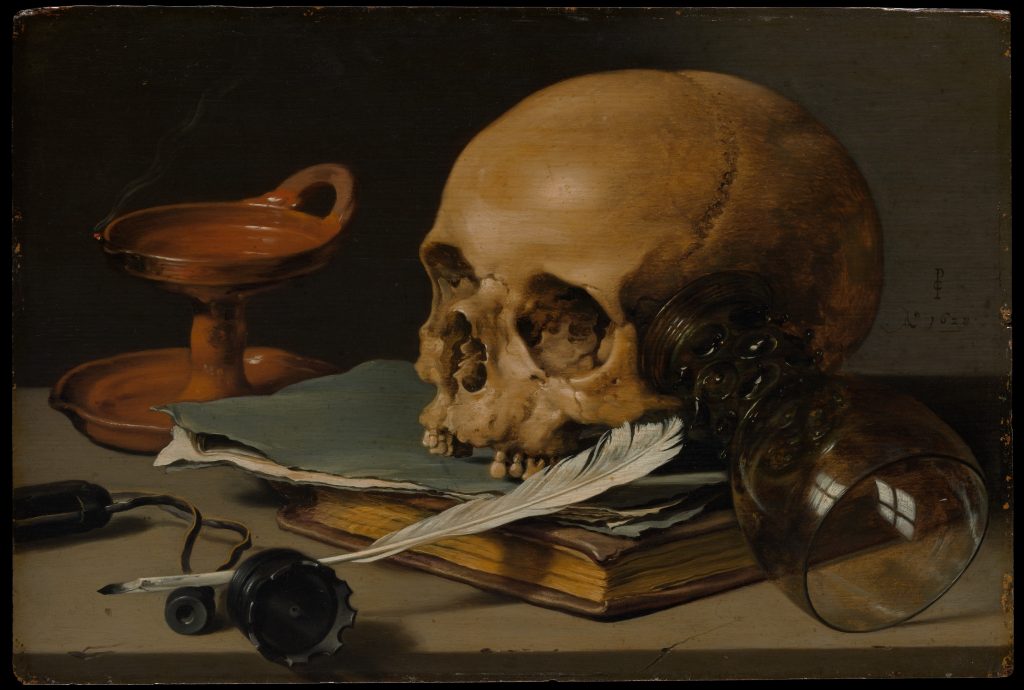

By Matthias Esho Birk Apr 04, 2025 Still Life with a Skull and a Writing Quill, Pieter Claesz, 1628. Oil on wood. Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art archive.

Still Life with a Skull and a Writing Quill, Pieter Claesz, 1628. Oil on wood. Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art archive. “To be, or not to be, that is the question” is arguably Shakespeare’s most famous line, perhaps the most famous in all of the English language. That it endures reveals something essential about the human mind—our preoccupation with the nature of existence itself.

Hamlet, the tragic prince of Denmark, whose father—the former king—has been killed by his own uncle, wrestles with this question of life and death. He continues in his soliloquy:

“Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles

And by opposing end them? To die—to sleep, No more.”

In simpler terms: Is this life, with all its suffering, worth the pain? Albert Camus, in The Myth of Sisyphus, framed it similarly: “There is but one truly serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide. Judging whether life is or is not worth living amounts to answering the fundamental question of philosophy.” Like Hamlet, Camus recognized that existence itself poses an existential dilemma.

The Buddha himself struggled with this question. So much so that he took the extraordinary step of leaving behind wealth, power, his young wife, and his young child to retreat into the forest in search of an answer—an answer to the suffering inherent in being alive. He came close to death: pushing himself to the brink through severe ascetic practices, he nearly starved. You may have seen paintings or statues of him in that state—looking more like a skeleton than a man. To be or not to be? That is the question.

The Buddha embarked on his ascetic journey after realizing that we all, including him, would inevitably face old age, sickness, and death. No one makes it out alive. I remember the exact moment it hit me: We all have to die, and nothing can stop it. The thought burrowed into me, cold and relentless. Wasn’t anyone going to do something about this? And on top of that, we can get cancer, be hit by a truck, or lose a loved one—and there’s absolutely nothing we can do to prevent it. This realization, undoubtedly, contributed to the birth of religions. The inevitability of suffering and the total vulnerability of our existence must have created the right psychological pressure for our ancestors to seek a mental “out”—to believe that if we cannot control any of this, at least a mighty God can. And if we don’t know what happens after death, at least a mighty God must have prepared a paradise for us to enter.

This led Nietzsche, in arguably his most important work, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, to preach a process of radical self-overcoming—living a life beyond belief, beyond external systems of meaning, whether religious, moral, or ideological. It also led him to proclaim (in one of his most famous lines) that “God is dead.” He implored: “I beseech you, my brethren, remain faithful to the earth, and do not believe those who speak to you of otherworldly hopes!” But if we let go of belief, what remains? And how do we live in this reality?

The Buddha’s great contribution was that he did not stop here. He did not remain caught in the question, like Hamlet, nor did he settle for mere rejection of external meaning, like Nietzsche. Instead, he sought a different path.

In one of the sutras from the Middle-Length Discourses, a monk confronts the Buddha:

“There are several convictions that the Buddha has left undeclared. . . For example: the cosmos is eternal, or not eternal, or finite, or infinite . . . after death, a realized one still exists, or no longer exists. . . The Buddha does not explain these points to me. I don’t endorse that, and do not accept it.”

The Buddha answers with a metaphor:

“Suppose a man was struck by an arrow thickly smeared with poison. His friends . . . would get a surgeon to treat him. But the man would say: ‘I won’t extract this arrow as long as I don’t know whether the man who wounded me was an aristocrat, a brahmin, a peasant, or a menial . . . and whether the arrowhead was spiked, razor-tipped, barbed, made of iron, a calf’s tooth, or lancet-shaped.’ ”

The Buddha didn’t get stuck in “to be or not to be.” When he realized that his extreme asceticism wasn’t leading to liberation, still scared and desperate, he sat under a tree and meditated. He breathed. And it was through the breath that he found freedom.

As a dedicated practice, we can learn to enter the stream of life, to truly live it, not just contemplate it.

A dear friend of mine and sangha member is a sheep farmer. Every spring is lambing season, and she recently shared a story about witnessing one of her ewes struggling with complications in labor and dying. When she realized the ewe wasn’t going to make it, she was distraught. Being an experienced meditator, she finally decided to just sit with the ewe and breathe with her—there was nothing left she could medically do. And she realized that in that moment, as she simply breathed with the ewe, the ewe was not contemplating life and death. The ewe was simply in the present moment. For all we know, the ewe wasn’t comparing her fate to others—Why is this happening to me and not the others?—or regretting past choices—If only I had lived a different life—or even fearing what was about to happen. The ewe was simply in the present moment. And in breathing, my friend was there with her.

The Buddha realized that old age, sickness, and death are not problems in themselves. It is the mind that makes them problems—by believing they shouldn’t happen, by insisting on figuring them out, resisting, controlling. That is why, in Zen, we talk about entering the stream. The mind is skilled at making up stories about life—what should happen, what shouldn’t, what shouldn’t have happened, what should have. How our life compares to others. What we desire and what we despise. Meanwhile, life happens. Right here.

As a mere thought, this realization may help us little. It is worth no more than a bumper sticker proclaiming “Be here now.” But, as a dedicated practice, we can learn to enter the stream of life, to truly live it, not just contemplate it.

“To be or not to be?” remains solely a question of the conceptual mind, unless we learn to actually be, without the question running circles around ourselves in our very own mind.

![]()

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.

KickT

KickT