Toxoplasmosis and Schizophrenia

The brain parasite toxoplasma may be one of the most important risk factors for schizophrenia. Toxoplasma “infects about one-third of the population of developed countries” […]

The brain parasite toxoplasma may be one of the most important risk factors for schizophrenia.

Toxoplasma “infects about one-third of the population of developed countries” and about one in four adults in the United States. However, the “life-long presence of dormant stages of this parasite in the brain and muscular tissues of infected humans is usually considered asymptomatic from a clinical point of view.” There is “a complex and dynamic interplay between the parasite, brain microenvironment [our brain], and the immune response that results in the detente that promotes the life-long persistence of the parasite in the host.” We can’t rid it from our brain, but we can at least keep it from killing us, unless we get AIDS or another disease that causes our immune defenses to drop.

“Within the past 10 years, however, many independent studies have shown that this parasitic disease…could be indirectly responsible for hundreds of thousands of deaths due to its effects on the rate of traffic and workplace accidents, and also suicides. Moreover, latent toxoplasmosis is probably one of the most important risk factors for schizophrenia.”

As I discuss in my video Does Toxoplasmosis Cause Schizophrenia?, schizophrenia does have a strong genetic component. But, even if you have the exact same genes as a schizophrenic—for instance, if your identical twin has schizophrenia—the chances of you having it are still probably less than 50 percent. So, what else might increase risk? As you can see at 1:22 in my video, studies performed over five decades in 20 countries found toxoplasma infection nearly triples the odds of schizophrenia, “which is more than any ‘gene for schizophrenia’ that has been described so far.” Now, obviously, everyone who gets this parasite in their brain does not develop schizophrenia. It may depend on where exactly in the brain the parasite takes up residence. But this “increased prevalence of toxoplasmosis in schizophrenics was demonstrated by at least 50 studies…”

Those were published studies, though. What about studies that weren’t published? Maybe some didn’t find any connection, or perhaps there were others that were just shelved. “In schizophrenia, the evidence of an association with T. gondii [toxoplasma] is overwhelming, despite evidence of publication bias.”

It’s still just an association, though. Instead of toxoplasma causing schizophrenia, maybe schizophrenia causes toxoplasmosis. “Institutionalized psychiatric patients may be fed undercooked meat, thereby increasing their exposure to T. gondii,” for example. That’s where military studies come in. “The U.S. military routinely collects and stores serum [blood] specimens of military service members,” which “affords a unique opportunity” to check people for infection well before the diagnosis of disease, so you can see which came first. And, indeed, the toxoplasma came first. The infection was found prior to the onset of psychotic symptoms.

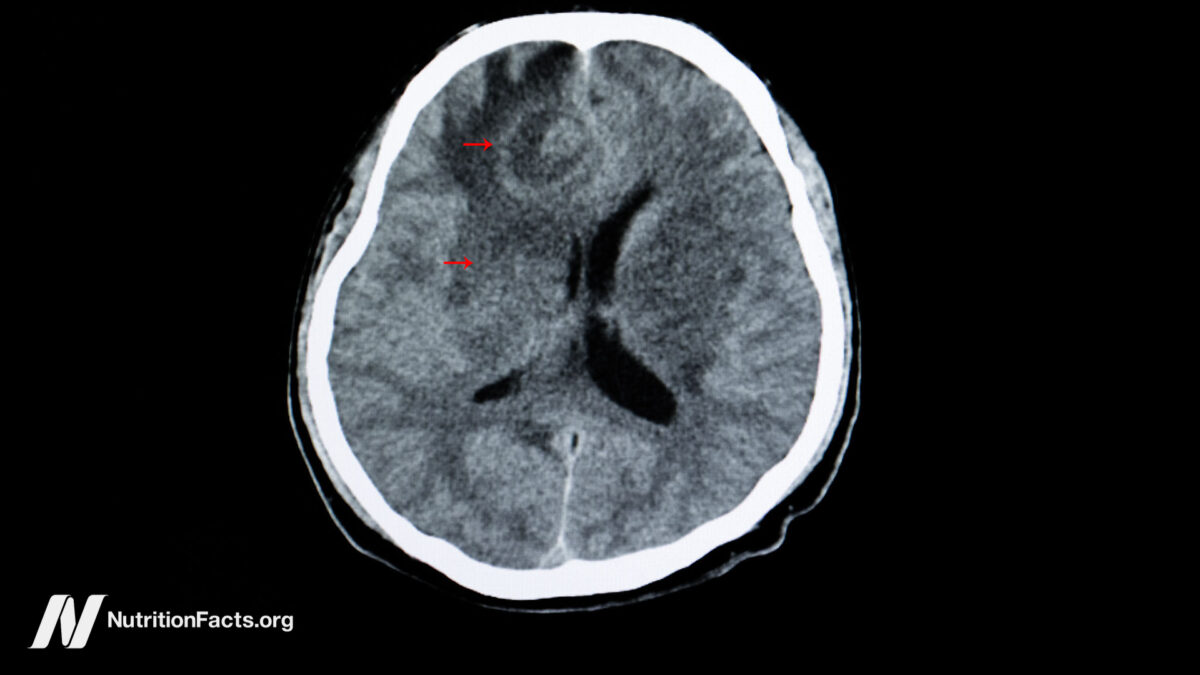

“The strongest evidence for the causal [cause-and-effect] role of Toxoplasma in triggering schizophrenia comes from a recent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study showing that differences in brain morphology [structure], originally thought to be characteristic of schizophrenia patients…are actually present only in the subpopulation of Toxoplasma-infected patients,” that is, only in those infected with the parasite. There are “gray matter anomalies” more often found in schizophrenia patients. But, as you can see at 3:12 in my video, when you divide the subjects into those who tested positive and negative for toxoplasmosis, you only really see it in the infected brains.

Does this mean we might be able to treat schizophrenia with antiparasitic drugs? There is a tetracycline-type drug, minocycline, that can kill toxoplasma in mice and seems to improve symptoms when given to schizophrenics, but it may also have independent anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective properties, so we don’t know if was a toxo effect. “Future research should look to delineate the antiparasitic effect of minocycline” by testing the patients for toxo to see if the drugs work better in those who have been infected.

There have been four randomized controlled trials specifically evaluating antiparasitic drugs in patients with schizophrenia, and no effect has been found. But, incredibly, not a single one of those studies used a drug that has been shown to actively kill off the parasites once they have been walled off in the brain. “After acute infection, parasites form walled cysts in the brain, leading to lifelong chronic infection and drug resistance to commonly used antiparasitics.” However, “there are currently no ongoing trials of anti-Toxoplasma therapy in schizophrenia despite ample evidence to justify further testing.” I hope a researcher reading this will realize the “time is ripe to evaluate antiparasitic drugs in Toxoplasma-infected patients with schizophrenia.”

This video is part of a series on toxoplasmosis, including:

Toxoplasmosis: A Manipulative Foodborne Brain Parasite Long-Term Effects of Toxoplasmosis Brain Infection How to Prevent Toxoplasmosis

JimMin

JimMin

![Are You Still Optimizing for Rankings? AI Search May Not Care. [Webinar] via @sejournal, @hethr_campbell](https://www.searchenginejournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/1-1-307.png)