Transforming Stuff into a Countable Number

Over a couple of years I’ve been reducing my possessions, and at last I’m down to what I can count. The few things around me are countable nouns–but it wasn’t always so. Many languages–including English–divide the stuff in the...

Over a couple of years I’ve been reducing my possessions, and at last I’m down to what I can count. The few things around me are countable nouns–but it wasn’t always so.

Many languages–including English–divide the stuff in the world into countable and uncountable nouns. Two cups of water are countable, but when we speak of the water in the ocean, that’s uncountable–an amount, not a number. Since the average American household is said to contain a rough estimate of over 300,000 items, it’s no wonder that, grammatically, we treat our stuff like it’s an ocean.

And not just in our grammar, either. Uncountable stuff is a real experience for so many of us. We open the junk drawer in the kitchen, or our bedroom closet, and the sight of all our stuff washes over us in a wave. We close the drawer, slam the door shut.

At the beginning of my own journey toward minimalism, I watched an episode of a home organizing show. The organizer gently led the homeowner into the bedroom and gestured to a huge pile of clean, unfolded laundry. She asked the owner to pick out one thing she really liked. The woman regarded the tilting mass, tilting her head along with it, and apologetically plucked out a gray tank top. Smiling, the organizer spread the shirt on the floor and meticulously folded it into a perfect square–a single, cared-for object. It was, I realized, not just a nice folding job, but a linguistic transformation: the uncountable became countable. The woman seemed to see this, too. She held up the folded shirt to admire it, and she spoke of her dream of a whole house like this, of a few well-kept things, in their place. Yes, I thought, no more piles, no oceans.

I think many of us have learned to see our stuff as a boundless supply that we dip into as needed. If we are asked to wear red to work on Tuesday to support a cause, we think, sure, there’s a red shirt in here somewhere. If we see a recipe for madeleine cookies that calls for a special madeleine baking pan, well, we have that, probably. We experience our homes as objects-on-tap.

Seeing our possessions this way explains why, despite our burdening abundance, we often go out on weekends to buy even more. Our sea of objects must wash up each thing our culture demands, or why else would we dust, sort, label, move, and worry about it all? So we buy the next thing, as well as a couple more storage bins to keep it all from breaching the flood walls and washing us away.

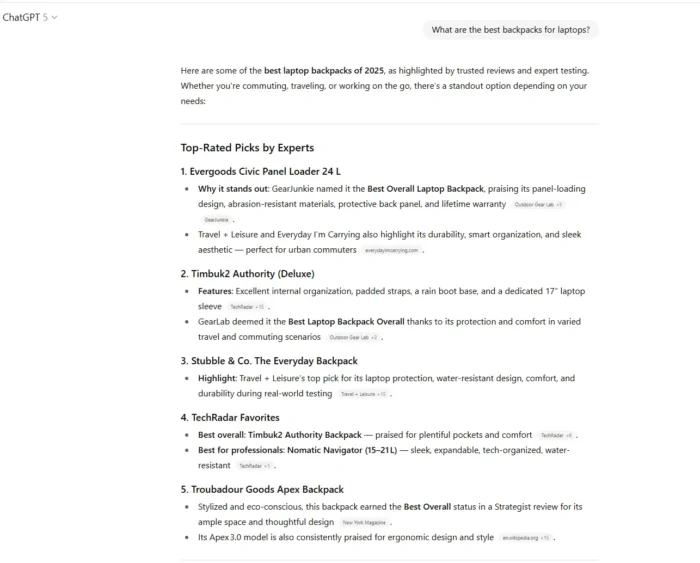

To declutter the average American home is to acknowledge that an object-on-tap system isn’t sustainable. Stuff can’t be treated as tap water. (Indeed, potable water is not so limitless as we’ve grown accustomed to viewing it, either.) A goal of a countable number of possessions helps. When the culture demands more and more stuff from us, we need to be able to say, no, sorry, I don’t have a red shirt, and I’m not going to buy one, because I don’t have an amount of shirts–I have a number, and it’s the number of shirts I need.

Making this happen is a big shift, and it takes time. In my own journey, I had to let go of my abundance of books, of craft supplies, of cooking tools, and of spilling-over teaching supplies that I thought might come in handy for my classroom, someday. And the thing is, occasionally something did come in handy–sometimes the object I wanted in a certain moment actually did wash up on the shore. But what I came to understand is that even more frequently, that one thing wasn’t in here. What I had was more of a sense of endless possibilities than the reality of it. Meanwhile, I had all this stuff around, and the chore of containing it all wasn’t something I wanted to do anymore. I let it go. My husband has been on a parallel journey, letting go of his tools, his collections, and his electronics.

Now, almost two years later, we have around us a few things we actually use on a regular basis. We are planning to do a lot of travel, and we have a tiny amount to store while we’re on the road. There is no more roar of the ocean in here, and we love it.

On your own journey, it’s important to go gently. Rally your courage and patience. Listen to the strategies of the decluttering experts out there, come up with a few of your own, and, most of all, give yourself time to turn a household of stuff into a manageable, countable number of things.

***

About the Author: Launa Hall retired early from teaching to travel with her husband, write, and read more books. Find her at Field Trip Notebook.

Fransebas

Fransebas