What Are the Best Foods for Gingivitis and Halitosis?

I discuss the best and worst foods for gum inflammation and bad breath. Yes, saturated fats produce an inflammatory response, and, yes, inflammation is “recognized […]

I discuss the best and worst foods for gum inflammation and bad breath.

Yes, saturated fats produce an inflammatory response, and, yes, inflammation is “recognized as one of the key underlying etiologic [causal] factors in periodontal disease.” That could explain why moderating our intake of meat and dairy could “promote periodontal health,” but plant-based diets don’t just offer lower levels of saturated fat, cholesterol, and animal protein. They also have higher levels of complex carbohydrates, dietary fiber, vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, and phytochemicals. So, we don’t necessarily know what the mechanism is. Saturated fat intake is associated with the progression of periodontal disease, but, at the same time, dietary fiber intake may be protective. Either way, you don’t know until you put it to the test.

As I discuss in my video Best Foods for Halitosis and Gingivitis, a randomized controlled trial investigated the effect of a dietary intervention on dental health. At seven months of age, more than a thousand infants were randomized, and about half were assigned to a low saturated fat and cholesterol intake to see if they get less heart disease when they grow up. They’re still just in their twenties, but, as children and adolescents, those randomized to the healthier diets ended up with better saliva production. The researchers had them chew on items like wax cubes, and those randomized since infancy to the better diet produced more saliva. “Saliva is essential for the maintenance of oral health,” for example, clearing out sugar and acid faster from our teeth. The researchers “believe that the greater increase of salivary flow was due to the greater intake of fibre-rich food items like grains, vegetables, fruit and berries requiring more chewing which in turn is known to increase salivary flow rate,” that is, saliva production. Is it possible the subjects’ bodies were just used to putting out more saliva? “In other words…in addition to general health benefits, dietary fibre may have benefits on oral health as well,” but it might not necessarily be the fiber itself but simply the act of chewing.

That reminds of me of another study I review in my video, in which a single high-fiber meal was able to reduce bad breath for hours. Halitosis is caused by gaseous sulfur compounds that are produced by a certain type of bacteria concentrated on the back of our tongue. When we eat, the reason bad breath gets better may be “due to the ‘self-cleaning’ of the mouth while chewing food.” So, it makes sense that foods that need to be chewed more intensively have a stronger self-cleaning effect on the back of our tongue than foods that require less chewing, but you don’t know until you put it to the test.

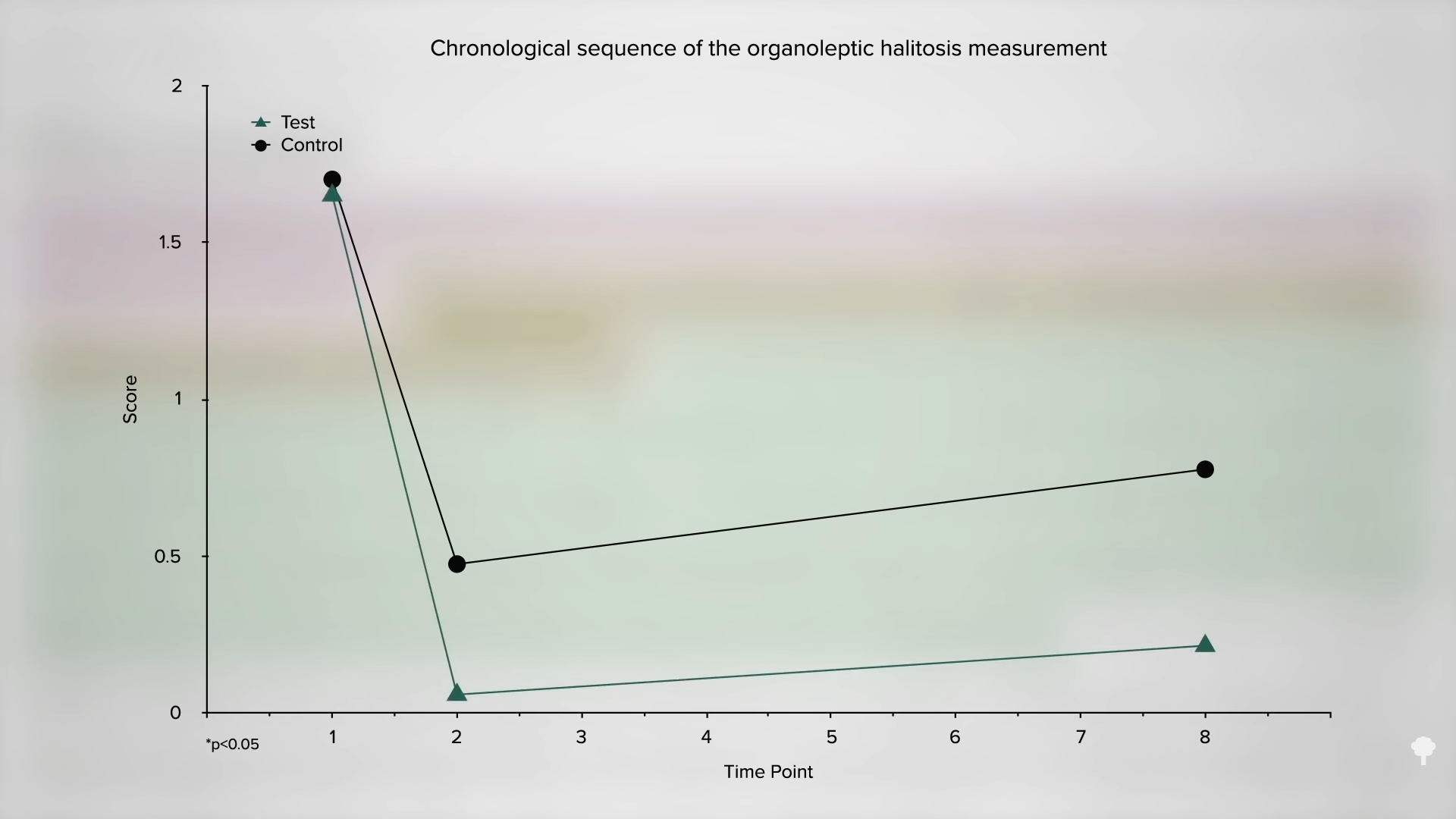

Study subjects ate two very similar meals: One had a whole–grain roll, a raw apple, and jam, so there was more fiber and more chewing, while the other meal had white bread, jelly, and cooked apples, so less fiber and less chewing. Then, the researchers measured the halitosis compounds in the participants’ breath at two hours after the meal and then again at eight hours. Bad breath levels dropped even after the low-fiber meal, but they dropped significantly more after the higher-fiber meal and stayed down even eight hours later, as you can see in the graph below and at 2:38 in my video.

The reason a high-fiber diet may improve periodontal disease may be the fiber, the lower saturated fat intake, or just the chewing—or perhaps another possibility. Maybe it’s the nitrate-containing vegetables. We know “the ingestion of dietary nitrate”—in the form of greens and beets—“has been proven to exert many beneficial and clinically relevant effects on the general health,” including maintaining good blood flow and reducing inflammation in general. So, might improved circulation to the gums and anti-inflammatory effects benefit periodontal patients?

Let’s find out. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial investigated the repeated consumption of lettuce juice? Why lettuce juice? That sounds so unappealing! Not to worry, though. “To improve patient acceptance,” the lettuce juice and the placebo juice were seasoned with a chamomile-honey flavor and sweetened with an artificial sweetener. (That sounds even worse!)

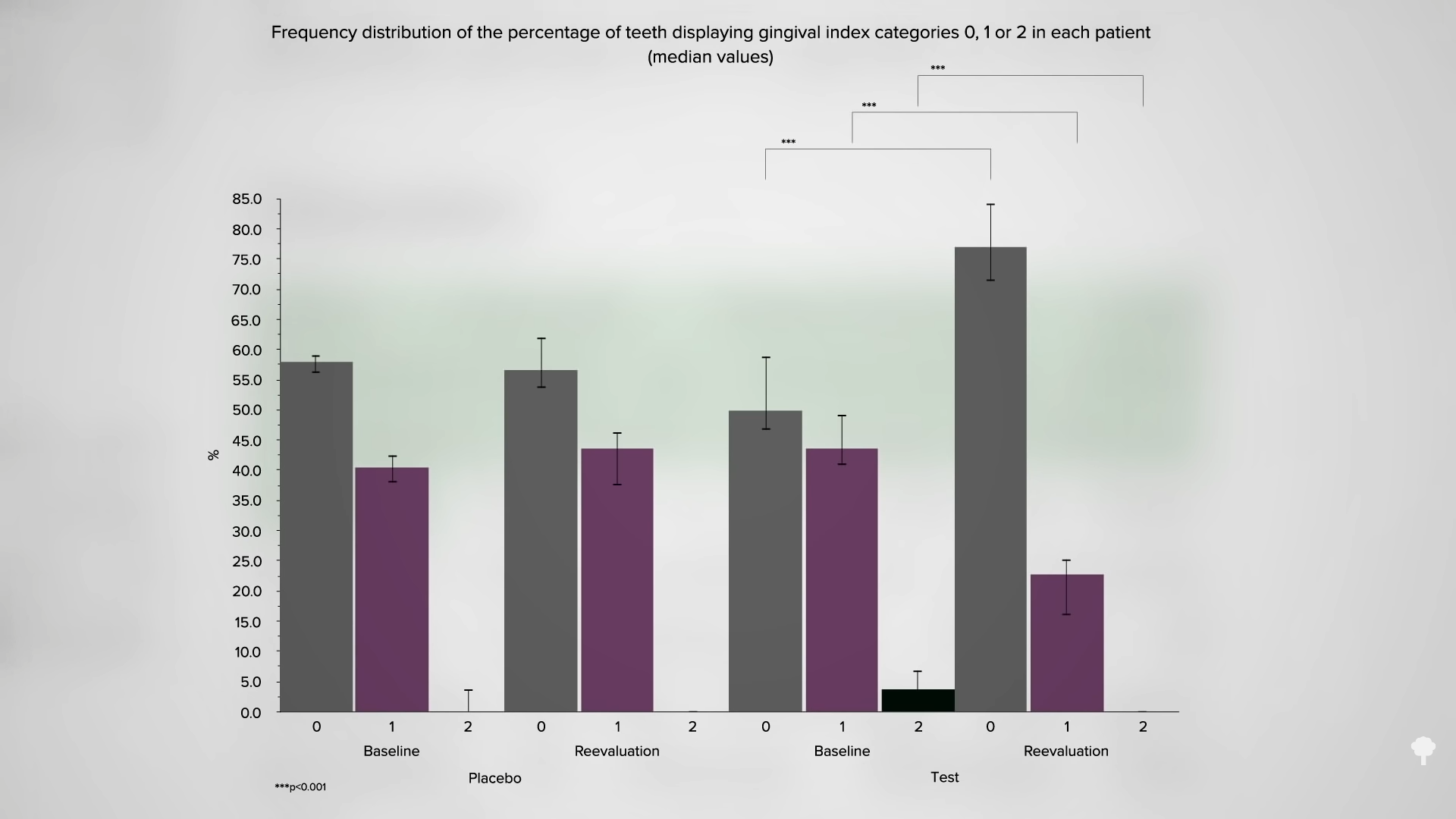

But, the lettuce juice concoction worked. “This clinical intervention trial demonstrated an attenuating effect of dietary nitrate on gingival inflammation.” You can see the results graphically below and at 4:00 in my video. In the placebo group, most of their teeth (about 60 percent) had no gingivitis, but 40 percent did have mild gingivitis and there was almost no moderate gingivitis. After drinking placebo lettuce juice for two weeks, there was no real change, as you might expect. In the lettuce group, they started out a bit worse; about half of their teeth had mild or moderate gum disease. But, then, after two weeks of actual lettuce juice, there were significant improvements. There was no more moderate disease, the mild disease rates were cut in half, and three-quarters of their teeth had no gingivitis at all.

The researchers concluded that their “findings suggest that the ingestion of dietary nitrate,” such as from greens and beets, “may be a clinically useful adjunct in the control of chronic gingivitis in periodontal recall patients.” They may be useful for controlling other chronic diseases, too. What’s good for the mouth—not smoking and eating a healthier diet, for instance—is good for the rest of our body. Many dental professionals, who may see their patients more frequently than do physicians, should be counseling them on living more healthfully. And, indeed, in one study surveying dental hygienists, “[n]early all (95%) felt that dental hygienists have a role in helping patients improve nutrition,” yet that’s not what happens at all. When a group of patients were asked, less than one in ten said they got dietary advice from their dental professionals. Why? Because “although dentists were motivated to include nutrition in their clinical care, most felt unqualified to provide dietary guidance and thus shied away from doing so.” That never stopped physicians!

But it’s true. Nutrition is neglected in dental school, just like in medical school, and, “in most cases, courses in nutrition education were taught by biochemists, and only a few individuals (hired part-time or on an ad hoc basis) had training in applied nutrition.” It’s really not rocket science, or is it? Get it? (Rocket is another name for arugula, an excellent source of dietary nitrite!) Dietary nitrate is hard to “beet!”

Konoly

Konoly