Words as Windows

Reading, writing, and the Zen paradox The post Words as Windows appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

Zen is often said to stand outside words and letters, pointing instead to a truth beyond language. Yet from the earliest Zen sermons to later memoirs and koan collections, it has always been a literary tradition. Even today, reading and writing play a central role in many practitioners’ awakening experience.

For readers, a single phrase can spark awakening; books become bridges to the other shore, not baggage. For writers, putting the self on paper reveals it as merely a fictional narrative. And because reading and writing often blur, entering a character’s consciousness can reveal that our own identity is just another fiction. For many prominent Zen authors today, both reading and writing, when done well, push us to abandon our egocentrism and move toward something broader and deeper.

While I refer to the whole tradition as “Zen,” it’s important to note that it goes by different names in Asia: Chan in China, Seon in Korea, and Thien in Vietnam, each with their own histories, practices, and flavors. The term “Zen” comes from the Japanese pronunciation of Chan, which became the conventional form in the West. I use the name “Chan” when referring specifically to the Chinese tradition.

Zen’s Literary Paradox

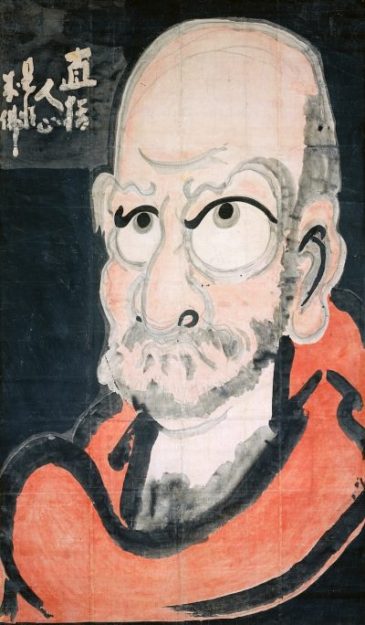

The idea that the Zen school has nothing to do with texts is usually attributed to the fierce Chan patriarch Bodhidharma. The rich artistic tradition of portraying Bodhidharma supports the notion of rejecting literature to return to raw naturalness. It brings us face-to-face with a bearded madman, the antithesis of the educated Chinese elite’s ideal of cultural refinement. In his famous encounter with Emperor Wu of the Liang dynasty, Bodhidharma dismisses the emperor’s temple-building efforts as worthless and claims not to know who he himself is. He is not interested in winning friends and influencing people. As if he were Charles Bukowski at a job interview, he refused to be anyone but himself. And he was, of course, no one.

Hakuin Ekaku’s Bodhidharma

Hakuin Ekaku’s BodhidharmaYou can tell a lot about a tradition by the types of people it cherishes. What Chan’s portrayal of Bodhidharma would say about the tradition is pretty straightforward: Stay away from artificiality, from cultured refinement. Don’t do things by the book but behave authentically and spontaneously, even if it clashes with etiquette or common sense. Even today, many Zen manuals unironically advise against reading Zen books, suggesting that Zen means abandoning ideas and returning to a beginner’s fresh, unconditioned mind.

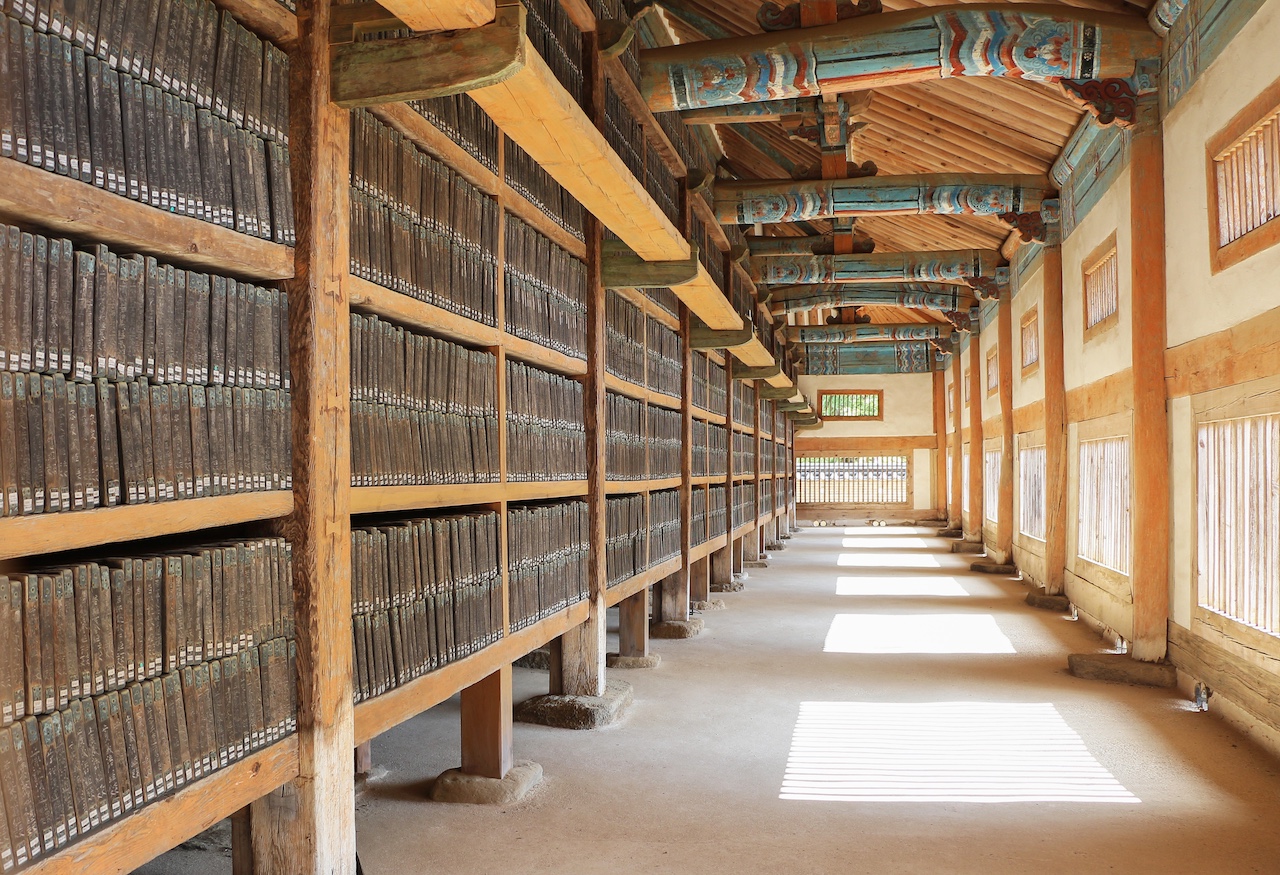

Another famous story illustrating Chan’s skeptical stance toward literature involves Deshan Xuanjian (780/2–865), originally a renowned scholar monk of the Diamond Sutra. He once held a lecture on this sutra that was so brilliant he was nicknamed “Diamond Deshan” thereafter. Dissatisfied with his level of understanding, Deshan traveled to meet the Chan master, Longtan Chongxin, bringing along his extensive writings on his back. On the way, a wise older woman discovered what he was carrying and questioned his grasp of the sutras with a pointed question, leaving him unable to answer and humbled. Later, at Longtan’s temple, Deshan experienced sudden awakening when the master handed him a candle to see his way in the dark and immediately blew it out, symbolizing the insufficiency of words. Realizing the master’s profound teaching, Deshan promptly torched his commentaries, proving his release from textual attachments.

Deshan’s symbolic rejection of texts didn’t halt the literary flourishing of the Zen tradition. From classical poetry and commentaries to contemporary memoirs, Zen Buddhists have long expressed insights through writing. Today, even lay practitioners contribute to a thriving genre that includes not only introductions to Zen philosophy and practice but also autobiographies and hybrids like Zen and the Art of Running, Zen and the Art of Making a Living, Zen and the Art of Dealing with Difficult People, and (one of my favorites) Zen and the Art of Navigating College. While this proliferation reflects a modern commodification of Zen, it isn’t entirely new. When Song dynasty monks imagined Bodhidharma’s life and painted his wild appearance, they too were trying to sell Zen to the imperial court.

We might interpret this cynically, as many of my students do, as human beings simply failing to live by their ideals, indulging in reading and writing despite Zen’s many admonitions. And yet some see these stories not speaking against books but against attachment to books. Many Zen monks and masters were outstanding scholars. This shows in their poetry, which is full of dense literary allusions, and in their essays, which show a profound grasp of Buddhist philosophy. The risk of becoming attached to books must have been significant; these stories warn against that. But it also warns against literalism and against mistaking the finger for the moon it is pointing to.

While many classical stories caution against clinging to texts, other stories in the tradition also reveal how words can jolt us out of certainty and into awakening. This paradox continues today. For many modern Zen practitioners, reading itself has sparked deep insight and even transformative realization.

Reading as Practice

If we let go of our attachment to words and letters, and instead let them point, amazing things can happen when we read and write. I became interested in Zen because reading a poem changed my life. When I was a senior in high school in my native Belgium, we were made to read poetry, which I had never been particularly interested in. But one poem, “What Is Known” (“Geweten”), by the Flemish idiosyncratic poet Jos de Haes, opened a door. In very condensed language, it took me into the cosmos. What the poem was saying, I discovered, was not something that I could describe. But it was saying it nonetheless. It was that experience that made me want to study literature in college.

One of the most influential American Zen teachers, Robert Aitken, also traced his path back to a book. During World War II, while a prisoner of war in Kobe, Japan, a guard lent him R. H. Blyth’s Zen in English Literature. Blyth argued that Zen-like insight could be found in Western writers like Shakespeare. Reading it triggered a series of “strange experiences” for Aitken, through which literature became “transparent,” revealing something beyond words. Despite the hardship of captivity, he felt “absurdly happy.” That reading experience became his first step on the Zen path.

Aitken is far from the only American Zen teacher for whom reading a text was so transformative. Bernie Glassman’s most powerful awakening didn’t happen in the zendo—it happened while reading in a carpool. Though he’d already gained insight into the koan “Mu,” he still struggled with core Buddhist ideas such as rebirth. His teacher, Taizan Maezumi, refused to give him direct answers and instead told him to read Philip Kapleau’s Three Pillars of Zen. Reading in the carpool to work, Glassman was overwhelmed. Laughing and crying at once, he told his fellow carpoolers there was nothing to worry about.

If we let go of our attachment to words and letters, and instead let them point, amazing things can happen when we read and write.

We can’t be sure what the exact passage was that Glassman found so transformative in Kapleau’s book, which is a thick Zen manual that includes speeches by Zen masters, koan commentaries, reports of private interviews between Zen masters and students, historical dharma talks by important Zen patriarchs, and instructions (with pictures) on how to properly sit while meditating. Also included in that book is a section called “Eight Contemporary Enlightenment Experiences of Japanese and Westerners,” which contains eight autobiographical narratives that end in enlightenment. The opening narrative is a testimony by “Mr. K.Y., a Japanese Executive, Age 47,” which includes yet another testimony of someone awakened by reading a book. Reading a book on Zen while riding on the train, this businessman comes across the following line: “I came to realize clearly that Mind is no other than mountains and rivers and the great wide earth, the sun and the moon and the stars.”

The quotation affects the executive deeply, and as he gets off the train, he cries in public. After going to sleep, he wakes up at midnight, and upon recalling the passage, he experiences a sudden, powerful awakening: “Heaven and earth crumbled and disappeared,” and the “empty sky split in two.” An intense joy made him burst into uncontrollable laughter, which sounded “inhuman” to his family. When he later visits his teacher, he confirms what the executive already knew: He had attained enlightenment. Again, reading a book sparked an all-encompassing transformation of a Zen practitioner.

Writing as Practice

If reading opens the gate to insight, writing leads us further inward, revealing how the stories we tell ourselves are constructed, and how we might let them go. One prominent American Zen practitioner and writer, Natalie Goldberg, has long seen writing as a Zen practice. In Writing Down the Bones, a best-selling writing manual, she identifies many commonalities between Zen practice and writing: Like Zen, writing is a discipline; like Zen, what you’re mapping when you write is the mind itself. But Goldberg also proposes that when true writing happens, no one is writing: “Only writing does writing—everything else is gone,” she says. Paradoxically, when we write down the story of our lives, the self disappears.

Goldberg doesn’t just talk the talk. In a memoir titled The Great Failure: A Bartender, a Monk, and My Unlikely Path to Truth, Goldberg describes her discovery that her teacher, Dainin Katagiri, was sleeping with some of his students. This traumatic discovery was amplified by an already existing trauma Goldberg had, which was connected to her father, Benjamin “Bud” Goldberg. Through the writing of The Great Failure, Goldberg comes to terms with the darkness in both parental figures. In the introduction, Goldberg writes, “If I could touch the dark nature in someone else, I could know it in myself. I wrote this book in the hope of meeting what’s real.” Throughout the process, Goldberg encounters painful aspects of herself that people usually shy away from. She explains that the “Great Failure,” drawing from Dogen, refers to hitting rock bottom—a moment of ultimate failure that reveals the false narratives we construct, often centered on success. Coming face-to-face with the Great Failure, which Goldberg calls “a boundless surrender,” undoes our self-deception, and writing, like a mirror, helps us to see ourselves more clearly.

My friend and colleague John Barbour has written about autobiographical Buddhist writing as a process of “un-selfing,” which he defines as “moments when a person’s sense of self is radically altered.” Though he doesn’t talk about Goldberg, how she describes writing fits in very well with his definition. The same applies to Ruth Ozeki, the famous author, filmmaker, professor, and Zen priest. Ozeki’s award-winning novel, A Tale for the Time Being, contains a character named “Ruth.” Although the book presents itself as fictional, Ruth has a lot of commonalities with the “real” Ruth Ozeki. In an interview, Ozeki notes that the fictional Ruth in her novel is related but distinct from herself, highlighting that representation inevitably involves “fictionalizing.” Her writing explicitly plays with the Buddhist understanding of self and no-self, showing readers how mindfulness helps us “hold [our] story lightly.” Ozeki suggests that writing allows you to see your identity as just one version among many, revealing no permanent self. In another book, her memoir The Face, she argues that literature—reading or writing—is like wearing a mask. It allows experimentation with other ways of being, loosening attachments to the self and freeing us rather than binding us.

Where Ozeki blurs the line between fiction and autobiography, Janwillem van de Wetering pushes even further, deliberately fictionalizing his Zen memoirs to reveal identity as a performance. Best known for his Zen-flavored detective fiction novels and initial exploration of monastic life in Japan, The Empty Mirror, Van de Wetering wrote his revolutionary Zen memoir, Afterzen: Experiences of a Zen Student Out on His Ear, near the end of his life. The book is scandalous. It portrays Zen as a big carnival, where nothing should ever be taken seriously, least of all the authority of Zen masters. Some contemporary masters are severely satirized, including Van de Wetering’s teacher, Walter Nowick. Yet near the end of the book, Van de Wetering pulls the carpet from underneath his readers’ feet by claiming that almost none of the teachers he has described are real. Instead, they are “collages, put together to carry certain ideas. The actors on this stage aren’t linked too closely to my actual life.”

The reader might have understood this if they had noticed something Van de Wetering wrote earlier in the book. He dismisses identity as a temporary personality, useful only as “a polite mask” to handle daily routines. Ultimately, he concludes, “I’m not my mask.” Revealing identity as merely a mask allows him to fictionalize his autobiography freely. Like Ozeki, he teaches readers to hold identity lightly. For Van de Wetering, this playful fictionalizing of self makes everything that happens in life, the good and bad, “fun.”

Letting Go of the Story

In Zen, stories can be both stepping stones and snares. The tradition has long warned against clinging to words, even as it uses them to reveal that the self is nothing more than a story we tell ourselves. This tension is not a flaw but a feature, pointing to how we might read and write not to define ourselves but to let go. The Chinese for Bodhidharma’s “not relying on words and letters” reads more literally as “not standing in words and letters.” That—admittedly clunkier—translation gives us a more vivid image: someone surrounded by words, someone sinking into letters as if they were standing in quicksand or a swamp. If we read it that way, it doesn’t seem too healthy. It rejects identifying with a book you wrote, as happened to Diamond Deshan. He was not doing the right thing by burdening himself, mentally and physically, with the weight of his own writings and opinions. He needed to use books to become himself but did not need to become his books.

If you feel like reading about Zen, read to your heart’s content. If your heart calls you to write, write. But know that the things you read can only point the way to the truth in yourself. And know that the things you write are not yours. They are everyone’s. And (thus) no one’s.

♦

Image credit: Hakuin Ekaku, Bodhidharma (Daruma), Edo period, 18th century. Image via Manju-ji Temple, Oita | Wikimedia Commons

Koichiko

Koichiko