AAPI Month: Asian American Buddhist Activism and Solidarity

For Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage month, we’re sharing articles by and about Asian American Buddhists from our archives. The post AAPI Month: Asian American Buddhist Activism and Solidarity appeared first on Lions Roar.

For Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage month, we’re sharing articles by and about Asian American Buddhists from our archives. This week, we’re exploring Asian American Buddhist activism and solidarity.

This week, we explore Asian American Buddhist activism and solidarity. Activism has many meanings and takes many forms: raising awareness about an issue, protesting, voting, creating art, working in service towards higher ideals, working in service towards smaller practical goals, and more. Similarly, solidarity can mean many different things: community-building, finding commonality despite difference, working together towards our collective liberation, and more.

Some may argue that Buddhism, with its many teachings on subjects such as loving-kindness, interdependence, and right action, enables activist practices. But what does it mean to actively incorporate Buddhist teachings into one’s activism?

In the following five articles, we see how Asian Americans’ Buddhist practice influence their activism, and how their activism influences their Buddhist practice. Tanny Jiraprapasuke reflects on experiencing a xenophobic verbal attack, pushing her to raise awareness about anti-Asian incidents during COVID-19, demonstrating that activism can mean speaking up as well as viewing others with compassion.

Rev. Christina Moon interviews Hawaiian Governor David Ige on compassion in governance and valuing immigrant contributions, an activism that harnesses the power of public office in serving his community. Myokei Caine-Barrett, Minna Jain, and Bo-Mi Choi discuss how Buddhists can use their sangha communities to create spaces to speak honestly, acknowledge the real-world effects of difference and power, and come together in shared understanding.

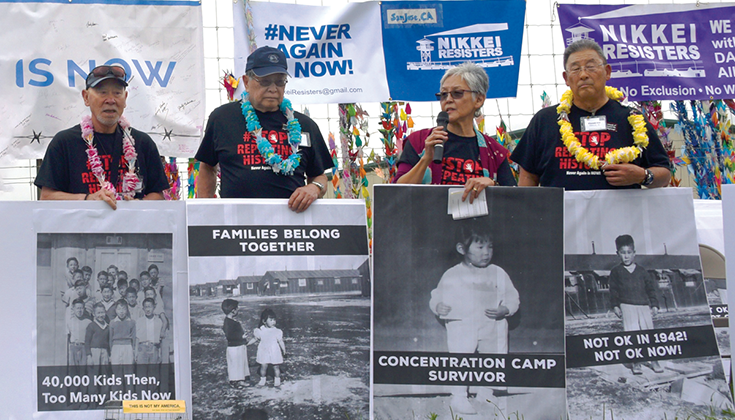

Finally, we have two creative pieces. Satsuki Ina shares two poems written after visiting Central American asylum seekers in detention centers at the U.S. southern border, revealing that activism can entail both working for the freedoms of those who are suffering as well as bearing witness to their stories. In a powerful spoken-word performance, George Yamazawa recounts how reflecting on our past mistakes can help our commitment to acting compassionately.

As you read these pieces, reflect on your own relationship with activism and solidarity. How do you contribute to the communities in which you live and/or find belonging? What Buddhist teachings represent activism or solidarity to you? How can you incorporate Buddhist concepts and practices into your activism? Into the contributions you make towards your communities? Into your daily life?

-Mihiri Tillakaratne, Associate Editor

How I Transformed Rage Into Compassion

As racist and xenophobic violence and discrimination rose amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, Tanny Jiraprapasuke chose to transform her rage into compassion for herself, her community, and beyond.

“I am exhausted from the rage I feel every single day, not at the man who said ugly things to me, but at a system that thrives by pitting our communities against each other.”

I speak these words to a crowd of hundreds as I stand on stage for the “Love Our Communities: Build Collective Power” rally in Little Tokyo.

A public health emergency due to the deadly Covid-19 had been declared by the World Health Organization on January 31, 2020. The media reported that the virus originated in a marketplace in Wuhan, China. Fear and anger toward the Chinese community was brewing.

Hawaii Governor David Ige on Buddhism and Politics in the Age of Trump

Governor David Ige — one of America’s most prominent Buddhist politicians — on immigration, climate change, and compassion in governance.

Cristina Moon: What does it mean to you to be Buddhist?

David Ige: For those who grow up Buddhist in Hawaii, we’ve always been Buddhist, so I’m not certain. It’s not like I changed religion.

When I speak with other Japanese Americans across the country who immigrated to California, Seattle, Chicago, or Washington, DC, it’s interesting because in virtually every instance, the primary motivation is to forget where you came from, try to assimilate as quickly as possible—trying American religions, trying to get into American schools and be as American as quickly as you can.

I think Hawaii is very different from the mainland. The First Nations of Hawaii truly were about respect for the culture and embracing immigrants. In Hawaii, we are encouraged to stay connected with where we came from. So, I’ve always been a Buddhist and it’s not something that’s ever apart from who you are. It’s a different kind of experience.

Asian American and Black Buddhist Teachers Reflect on Racial Solidarity

Three Asian American and Black Buddhist teachers reflect on healing, solidarity, and how Buddhists of color can work together for greater racial justice.

I exist because of death and destruction, born after war to a Japanese mother and a Black American father. This duality meant there was no real welcome in Japanese or Black communities, only in those mixed ethnic spaces inhabited by war-born families. I have always been either invisible or exotic, the target of those bold enough to either ask or to advance their own ideas of who I am. I share my story so it is understood that I have skin in this game; because I have lived the racism toward Asian and Black Americans. My family today includes also Latino and white, differently-abled as well as LGBTQIA folks—a range of cultures, and religious and philosophical ideas—all grounded in absolute acceptance and love of kinfolk.

We Will Come Back for You

Not so long ago their own families were held in camps like these. That’s why Japanese American Buddhists like Satsuki Ina will keep coming back until the tragedy on America’s southern border ends.

In March, I joined sixty other Japanese American and Japanese Latin Americans who paid homage to parents and grandparents who had been unjustly incarcerated during WWII at the Crystal City, Texas Family Internment Camp. We were reminded of the interconnectedness of all things as we proceeded to Dilley, Texas, where today 2,400 Central American women and children seeking asylum are being unjustly detained in prison facilities.

We wanted the children inside to know that someone outside cared. We wanted the world to know that we will not be silent when people are suffering at the hands of a cruel and unjust government policy so resonant of our own family experience.

In this mic-dropping poetry slam, George Yamazawa out-logics slurs with Buddhism

A number of Buddhists united against anti-Asian violence and racism on May 4 at “May We Gather: A National Buddhist Memorial Ceremony for Asian American Ancestors.” Read a selection of wisdom shared by Buddhist leaders at the ceremony.

In this powerful slam performance, award-winning poet George Yamazawa recounts his earliest memories of teasing classmates by calling them “gay,” and the reaction he got from his Buddhist father. In rhythmic verse, Yamazawa talks about the power of words as insults and poetry, and the love that Buddhism inspires.

“I forgot that the voice does the work of the Buddha. So why would I ever call someone gay before calling them beautiful?”

BigThink

BigThink