5 Great Meditation Teachers

Beginning with the Buddha himself, five extraordinary teachers instruct us in the practice of calming the mind, cultivating awareness, and — ultimately — finding freedom. The post 5 Great Meditation Teachers appeared first on Lions Roar.

Beginning with the Buddha himself, five extraordinary teachers instruct us in the practice of calming the mind, cultivating awareness, and — ultimately — finding freedom.

“Buddha Expounding the Dharma,” Sri Lanka, ca. 750–850CE, courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Buddha

The original mindfulness teacher.

Looking into meditation for the first time, a beginner won’t search long before coming across the Buddha. It can fairly be said that the Buddha was the world’s first mindfulness teacher. He taught mindfulness meditation to his disciples, and his teachings in sutras like The Four Foundations of Mindfulness were the first systematic and detailed presentation of mindfulness practice.

Born a prince known as Siddhartha Gautama, he lived a sheltered existence until excursions outside his palace revealed to him the sad facts of sickness, aging, and death. Shaken by the suffering he saw, he ventured into the world on a spiritual quest to find an answer. He sought out renowned teachers and undertook many intense practices, but nothing worked. Finally, seated under the Bodhi Tree, he stopped all spiritual struggle and simply rested in his own true nature and the true nature of reality, achieving enlightenment.

It is said the Buddha then stayed under the Bodhi Tree for another seven weeks as he pondered how best to teach this to others. What he came up with was a combination of mindfulness practice, wisdom, and ethical living that came to be known as the noble eightfold path to enlightenment.

Teaching: Contemplate the Body in the Body

How, monks, does a monk dwell contemplating the body in the body? Here a monk, gone to the forest, to the foot of a tree, or to an empty hut, sits down; having folded his legs crosswise, straightened his body, and established mindfulness in front of him, just mindful he breathes in, mindful he breathes out. Breathing in long, he understands: “I breathe in long”; or breathing out long, he understands: “I breathe out long.” Breathing in short, he understands: “I breathe in short”; or breathing out short, he understands: “I breathe out short.” He trains thus: “I will breathe in experiencing the whole body”; he trains thus: “I will breathe out experiencing the whole body.” He trains thus: “I will breathe in tranquilizing the bodily formation”; he trains thus: “I will breathe out tranquilizing the bodily formation.” Just as a skilled lathe-worker or his apprentice, when making a long turn, understands: “I make a long turn”; or, when making a short turn, understands: “I make a short turn”; so too, breathing in long, a monk understands: “I breathe in long” … he trains thus: “I will breathe out tranquilizing the bodily formation.”

In this way he dwells contemplating the body in the body internally, or he dwells contemplating the body in the body externally, or he dwells contemplating the body in the body both internally and externally. Or else he dwells contemplating in the body its nature of arising, or he dwells contemplating in the body its nature of vanishing, or he dwells contemplating in the body its nature of both arising and vanishing. Or else mindfulness that “there is a body” is simply established in him to the extent necessary for bare knowledge and repeated mindfulness. And he dwells independent, not clinging to anything in the world. That is how a monk dwells contemplating the body in the body.

Again, monks, when walking, a monk understands: “I am walking”; when standing, he understands: “I am standing”; when sitting, he understands: “I am sitting”; when lying down, he understands: “I am lying down”; or he understands accordingly however his body is disposed.

In this way he dwells contemplating the body in the body internally, externally, and both internally and externally…. And he dwells independent, not clinging to anything in the world. That too is how a monk dwells contemplating the body in the body.

From In the Buddha’s Words: An Anthology of Discourses from the Pali Canon, by Bhikkhu Bodhi (Wisdom Publications).

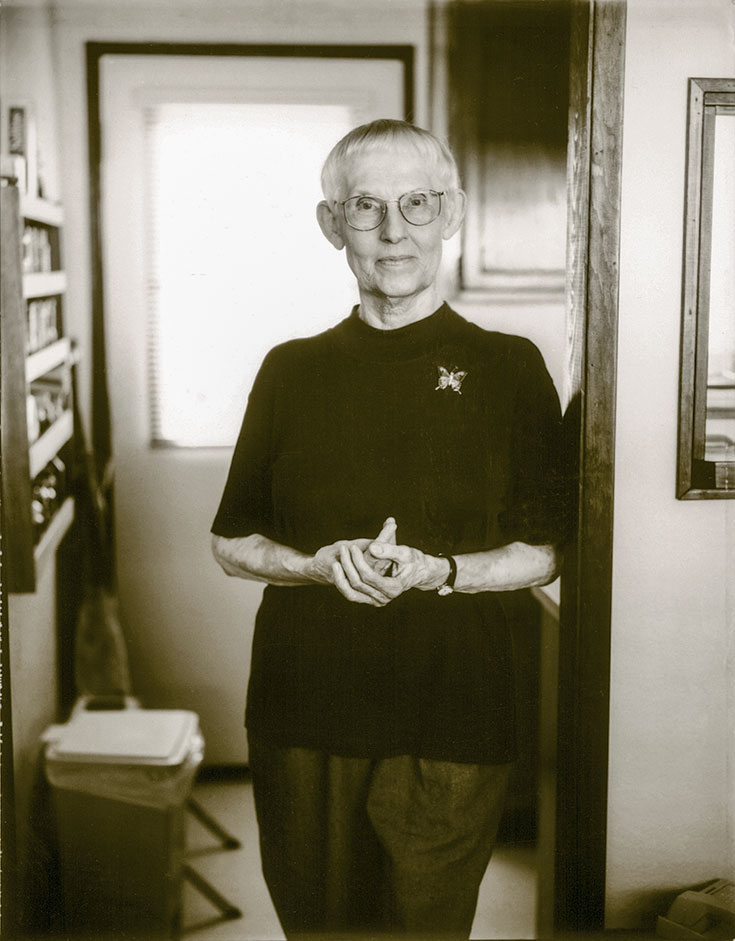

Photo by Michael Lange www.michaellange.de

Charlotte Joko Beck

She brought modern psychology to bear on meditation—Zen would never be the same.

One of the first Western women Zen teachers, Charlotte Joko Beck had a profound impact on the practice of Buddhist meditation in America. Coming to Zen after raising a family, Beck revolutionized how meditation connects with one’s personal psychology.

Authoring two modern Zen classics—Everyday Zen: Love and Work and Nothing Special: Living Zen—Beck challenged traditional methods of teaching meditation that failed to address emotions such as anger, anxiety, and selfishness. Creating a bridge between Zen practice and modern psychology, Beck made working with one’s psychological state a central aspect of a practitioner’s time on the meditation cushion.

“We are all caught up in frantic thinking,” Beck wrote in Everyday Zen, “and the problem in practice is to begin to bring that thinking into clarity and balance. When the mind becomes clear and balanced and is no longer caught by objects, there can be an opening—and for a second we can realize who we really are.”

Ordinary Wonder, a posthumous collection of Beck’s teachings, was recently released.

Teaching: Your Own Core Pain

When we practice, we develop a basic vision, which gets stronger over time, as to who we are and what we’re really doing in our life. When I say “a vision,” I don’t mean something mystical. I mean acknowledging who you are and what you want to do next.

I have found that most human beings, particularly Western-raised human beings, feel fundamentally they’re worthless. Really worthless. Unless we’ve been practicing for a long time or are extraordinarily lucky in how we were brought up in the world, most of us feel this. We have our own little quirks that give our sense of worthlessness a personal flavor and style, but that’s what it is. We don’t want to feel worthless. We don’t even want to hear or know about it. It’s very, very painful to feel that you’re worthless or unlovable. That feeling creates a running tension that we may be unaware of until we sit—and then it all comes out.

Suppose I’m covering this core belief in my own unworthiness by being very sweet and helpful, always available for others. What does that feel like? Just stop and feel it. Chances are high that there’s fear and anger in all that sweetness. Most of us don’t need to go looking for this core belief as if it’s something well-hidden.

It’s what you can become aware of every second if you stop and sit. Pay attention: something is there.

Life is never hidden because you’re living your life through this body every second. It’s always right here and right now. You don’t have to ask, “What does Joko mean by that pain? Where is it?” The minute you stop thinking (the thinking is covering the pain) and the minute you stop doing (the doing is covering the pain), you feel it. It’s not always dramatic. That’s why sitting is so important. As you turn away from your thoughts and get back into the body, you’re experiencing your own core pain. It’s never hidden. It’s always right here.

And as we sit, as we develop the power and sensitivity to watch those thoughts cascade around, we learn an enormous amount about ourselves. We begin to sense—if we haven’t already—the enormous pervading tension inside us. Though we may not have noticed, it has been there for as long as we can remember.

From Ordinary Wonder: Zen Life and Practice, by Charlotte Joko Beck, edited by Brenda Beck Hess (Shambhala Publications).

Photo by Andrea Roth

Pema Chödrön

Become comfortable with uncertainty, says this beloved Buddhist teacher.

In tough times, people turn to American Buddhist nun Pema Chödrön. Her best-selling books like The Wisdom of No Escape, Start Where You Are, and When Things Fall Apart are passed around by those looking for wisdom and practices that help when life’s many challenges arise.

Reeling from the dissolution of a marriage in her thirties, Pema Chödrön sought various therapies and spiritual traditions to help

her cope, to no avail. Buddhist meditation, however, revealed the root of her suffering to her.

“The most fundamental aggression to ourselves, the most fundamental harm we can do to ourselves,” she writes in When Things Fall Apart, “is to remain ignorant by not having the courage and the respect to look at ourselves honestly and gently.”

According to Pema Chödrön, when we are confronted with difficult times in our lives and feel as if things are breaking apart, we only produce more suffering when we attempt to put the pieces back together. Instead, when we bravely choose to rest in the uncertainty and meet suffering without running away, awakening occurs. Pema Chödrön encourages us to train ourselves to look unflinchingly at the reality of our lives through the practice of meditation.

Teaching: The Power of Meditating on the Senses

You can use anything as an object of meditation. You can use anything that’s happening to you, whether it’s the arising of thoughts or strong emotions or sense perceptions. Your object can be sheer delight for you, or it can be sheer misery. It’s your choice.

For example, if you focus on a smell during your meditation, you might find yourself thinking, “That’s a terrible smell! We shouldn’t use that kind of incense” or “Oh, they’re burning the oatmeal, and when I eat burned oatmeal I get terrible indigestion and I don’t feel well for days.” Once again you’re off, and you’re angry at the cook and you’re packing your bags and you’re leaving the meditation retreat. And it was all because of a smell!

Meditating on our sense perceptions—hearing, sight, feeling, tasting, and smelling—helps us to see that even the littlest thing can turn us toward full-blown internal warfare. Or a sense perception can just run us around in circles and keep us living in a fantasy world. They can show us how, basically, we cause our own suffering because we allow the most simple sense to bring back a memory that can then escalate difficult emotions.

On the other hand, they also are opportunities for us to enter pleasure, delight, and joy. The senses are so alive, and they can bring us right to the center of the present moment.

Meditating with the sense perceptions allows us to directly connect with the immediacy of our experience, which is our gateway to limitless experience, the vastness of this world. Again, these very same sense perceptions can keep you locked in. A sound can trigger a memory from a decade ago. A smell might make you think of how you need to clean out your refrigerator.

When we meditate with our sense perceptions, we interrupt the momentum of thoughts and come back to the sound, or the smell, or the feeling, or whatever sense you’ve chosen to place your attention on. If you can start to practice this way with every little thing throughout your day, you’ll find that when challenges arise, you have tools for practice. You’re used to interrupting the momentum of a trail of thoughts, such as “There’s something wrong here that I have to solve,” or “I’m a failure,” or whatever the familiar story is. Through meditation, you’re training in interrupting the momentum of the wandering mind and going right to the experience itself.

From How to Meditate: A Practical Guide to Making Friends with Your Mind, by Pema Chödrön (Sounds True).

Ajahn Chah

His teachings were straightforward: “The serene and peaceful mind is the true epitome of human achievement.”

“Looking for peace is like looking for a turtle with a mustache,” Ajahn Chah once taught. “You won’t be able to find it. But when your heart is ready, peace will come looking for you.”

To keep his heart ever ready, Ajahn Chah, a key figure in the Thai Forest tradition of Theravada Buddhism, learned to meditate anywhere: in jungles with tigers and cobras, in cremation grounds, in rainstorms. After wandering in search of wisdom, he founded Wat Nong Pah Pong, a monastery in Thailand where monastics live in strict austerity to cultivate mindfulness and understanding.

Ajahn Chah’s dharma talks exhibited a direct style, with a focus on practical application that attracted a large following of Thais and Westerners. In fact, a number of Ajahn Chah’s students from the West, including Ajahn Sumedho and Jack Kornfield, established monasteries and meditation centers in the U.K. and America, popularizing Vipassana meditation, a practice rooted in the Theravada tradition.

“Peace is within oneself to be found in the same place as agitation and suffering,” Ajahn Chah taught, emphasizing diligence and courage in meditation, in a dharma talk recorded in the book No Ajahn Chah: Reflections. “Where you experience suffering, you can also find freedom from suffering. Trying to run away from suffering is actually to run toward it.”

Teaching: Quieter & Quieter

The most useful method, one that can be practiced by all types of people, is mindfulness of breathing. It is the developing of mindfulness of the in-breath and the out-breath.

In this monastery we concentrate our attention on the tip of the nose and develop awareness of the in- and out-breaths with the mantra Bud-dho. If the meditator wishes to use another word, or simply be mindful of the breath moving in and out, this is also fine. Adjust the practice to suit yourself. The essential factor in the meditation is that the noting or awareness of the breath should be kept up in the present moment so that one is mindful of each in-breath and each out-breath just as it occurs. While doing walking meditation we try to be constantly mindful of the sensation of the feet touching the ground.

To bear fruit, the practice of meditation must be pursued as continuously as possible. Don’t meditate for a short time one day and then, after a week or two, or even a month, meditate again. This will not yield good results. The Buddha taught us to practice often and to practice diligently, that is, to be as continuous as we can in the practice of mental training. To practice effectively we should find a suitably quiet place, free from distractions.

Suitable environments are a garden, in the shade of a tree in our backyard, or anywhere we can be alone. If we are monks or nuns, we should find a hut, a quiet forest, or a cave. The mountains offer exceptionally suitable places for practice. In any case, wherever we are, we must make an effort to be continuously mindful of breathing in and breathing out. If the attention wanders, pull it back to the object of concentration. Try to put away all other thoughts and cares. Don’t think about anything—just watch the breath. If we are mindful of thoughts as soon as they arise, and keep diligently returning to the meditation subject, the mind will become quieter and quieter.

When the mind is peaceful and concentrated, release it from the breath as the object of concentration…

All things in the world have the characteristics of instability, unsatisfactoriness, and the absence of a permanent ego or soul. If you see all of existence in this light, attachment and clinging to the khandhas will gradually be reduced. This is because you see the true characteristics of the world.

From Food for the Heart, by Ajahn Chah (Wisdom Publications).

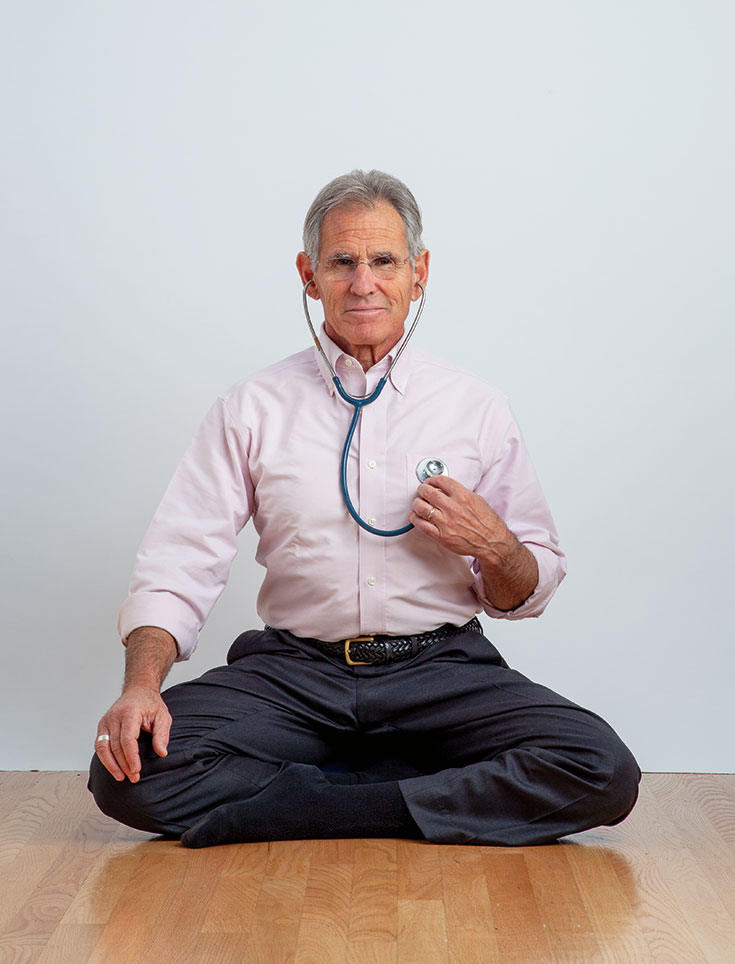

Photo by Joshua Simpson

Jon Kabat-Zinn

With his stress-reduction program, he brought mindfulness to the mainstream.

Jon Kabat-Zinn does not identify himself as a Buddhist meditation teacher. But he is a Buddhist and he teaches meditation. In fact, as the leading figure in the secular mindfulness movement, he has brought more people to mindfulness meditation than anyone else in our time.

In the late 1970s, Kabat-Zinn developed a program called Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) to help people suffering chronic pain.

Kabat-Zinn describes mindfulness as “moment-to-moment, non-judgmental awareness.” “Life only unfolds in moments,” he writes in Full Catastrophe Living, his best-selling book about the MBSR course. “The healing power of mindfulness lies in living each of those moments as fully as we can, accepting it as it is as we open to what comes next—in the next moment of now.”

Patients were taught conscious breathing, meditation, yoga, and incorporating mindfulness into daily routines. Focusing on the provable benefits of mindfulness in a non-Buddhist context, it was the start of a mindfulness movement that has today reached millions around the world.

Teaching: The Cascading Mind

The ocean is not the only metaphor for the mind, and waves are not the only metaphor for thoughts. There are many useful images that might provide new angles and novel approaches for working mindfully with thoughts and the process of thinking.

For instance, thoughts can be likened to the bubbles coming off the bottom of a pot of boiling water: they nucleate at the bottom, rise to the surface, and dissipate unimpeded into the air. Alternatively, you might imagine the energy of the thinking mind as the flowing of water in a stream or a great river. We can either be caught up in the stream and carried away by it, or we can sit on the bank and apprehend its various patterns with our eyes—the eddies and whirlpools ever-arising, changing form, and passing away—and with our ears as we drink in its various gurgles and songs. Sometimes thoughts cascade through the mind like a waterfall. We might take some delight in this image, and visualize ourselves sitting behind the torrent in a little cave or depression in the rock, aware of the ever-changing sounds, astonished by the unending roar, resting in the timelessness of the cascading mind in such an extended moment.

The Tibetans sometimes describe thoughts as writing on water, in essence empty, insubstantial, and transient. I love that. Skywriting is another apt image. Touching soap bubbles is another lovely metaphor. In all of these images, thoughts can be seen to “self-liberate,” to go poof just like soap bubbles when they are touched, or in our case when they are “touched” by awareness itself—in other words, when they are recognized as thoughts, simply events arising, lingering, and passing away in a boundless and timeless field of awareness.

We see that thoughts, when brought into and held in awareness in this way, readily lose their power to dominate and dictate our responses to life, no matter what their content and emotional charge. They then become workable rather than imprisoning. And thus, we become a bit freer in the knowing and the recognizing of them as events in the field of awareness. They become workable without our having to do any work—it is the awareness that does all the work and the liberating.

From Mindfulness for Beginners, by Jon Kabat-Zinn (Sounds True).

Kass

Kass