Aaron Alexander: Body Mechanics Go Beyond The Physical | Better Man Podcast Ep. 003

Aaron Alexander believes that if you want to change the quality of your life, you first need to change the way you move through your life. To do that, you need to align your mind, body, and movement. Aaron...

Episode 003: Making Fitness Who You Are, Not What You Do | Aaron Alexander – Transcript

Dean Pohlman: Alright, hey, guys, what’s up? It’s Dean. Welcome to the Man Flow Yoga podcast. I’m very excited today to be joined by Aaron Alexander of the Align Method. Aaron, please say hi.

Aaron Alexander: Hello.

Dean Pohlman: Perfect. Thank you so much for being here. So, I am going to start off telling the story of when we first hung out. So, I met you at a conference here in Austin. And I can’t remember how we connected on social media, but it happened one way or the other. And I think I just said, “Hey, you want to go to Barton Creek?” If you’re not familiar with Austin, Barton Creek is this amazing creek that has water that’s 69 degrees year-round, super cold, but not too cold, just really refreshing. It comes from five natural springs. It’s a great place just to go, hang out, be in nature, but it’s like two minutes from downtown.

So, we meet up at Barton Creek and we all see these guys using this kind of, it looks like a natural slide. There’s water rushing down the creek, and people have found this rock formation that’s a natural slide. So, I’m assuming Aaron being Aaron takes off his shorts to reveal the David statue boxer briefs, where you have these…

Aaron Alexander: That’s funny. I remember those. I got those in Italy. It was like my only souvenir from five months in Europe.

Dean Pohlman: I would hope that you got those in Italy. I mean, I don’t know where else you would buy them. So, Aaron is wearing these boxer briefs with a very nice statue penis on them and unabashedly playing in the water. So, that was one of my first impressions of Aaron, and I just wanted to share that with you. I think it sets the tone of how playful you may be, which is a huge theme in your book anyways.

Aaron Alexander: Sure, there’s a whole chapter about play, the power play, and the meaning of play. So, I appreciate that. I had no recollection of those. I don’t know where those David Wang stone penis shorts are. Now, I actually like I have something to rediscover. So, thank you.

Dean Pohlman: You’re very welcome. I mean, thank you. I got to experience that. Thank you.

Aaron Alexander: Yeah, I appreciate it.

Dean Pohlman: Oh, alright. So, we share, gosh, I don’t know even where to start, there’s so much talk about. So, we actually share a lot of overlap with customers and followers. If you look at my book, if you scroll down a little bit on Amazon, you could see you as one of the first recommended authors. So, Kelly Starrett also wrote the foreword for both of our books, which is a really great foreword, by the way. I really enjoyed reading that. And we just have a lot of overlap. So, I’m just curious, we focus on mobility, we’re both really, really ridiculously good-looking bearded men. What do you think we share in common? Why do we have so much overlap with our customers, followers?

Aaron Alexander: Well, I mean, I think that likely, I would imagine it’s just a genuine curiosity to understand how to work this human experience, human body better. That’s something that presently, both of us are in like a book launch phase month. And I’m hearing and doing a lot of interviews. And in that time, I’m just like, I personally feel immensely humbled and grateful to even have the opportunity to be able to have conversations with people and to humbly act as kind of like a voice box of my own exploration into how to feel more comfortable in my body. And so, I think, just a genuine interest in problem-solving and understanding how to feel better, how to feel more comfortable, how to feel more at home in our bodies, I think probably that would be likely concealing it’s between us.

Dean Pohlman: Yeah, I mean, and that answer just kind of leads me straight into what I want to talk about, which is a huge part of this conversation being the Align Method. And I started reading this. I open the book thinking, okay, he’s going to take us through kind of his workout program and recommended movements. And as soon as it started, I realized this was much different than what I expected. This isn’t just about exercises to do to keep your body aligned, this is exercises, daily habits, daily movement habits that integrate with not only the way that we move and are active, but also, in how that relates to how we think, how we feel. And I started reading it, well, for the sake of transparency and everything.

I was reading it last night before we had this conversation and I read about half of it in just one night as I could. And I just thought it was really great, how you outline these things that are, I mean, a lot of it’s basic, but a lot of it’s just the importance of doing it and being aware of all the things that it’s affecting. So, do you want to talk a little bit about a few methods from or a few practices from the book?

Aaron Alexander: Well, yeah, I mean, I so greatly appreciate the ease that you experience with going through because that was kind of the whole intention with creating it was taking complex ideas and simplifying them for anybody, their mom and their aunt and their uncle to be able to digest, making like a field manual for just living more effectively in your body, making better physical decisions, which all that’s tied back into the way that we produce ourselves in every level at an endocrinological level, at a hormonal level, at a mental/emotional level, at a structural level. Body language is the way that we communicate to each other.

So, in the book, I mentioned a UCLA professor called Albert Mehrabian from the 60s. He came up with the principle called the 55-38-7 principle, which essentially is 55% of our communication comes from body language and 38% is the tone of our voice and then 7% is the words that we’re actually using with each other. And so, as we’re speaking to each other, I think, maybe, we have a little bit more of like this, somewhat of like a mechanistic mindset of the way that we perceive things. And I think a part of that mechanistic mindset is the sense or story or idea that maybe like the words are really what’s packing the information.

But we’re communicating through feel, and a part of that feel, which is kind of like a meta, like oh feel, like, oh boy, like vibes, what are we talking about here? We’re communicating literally millions of visual bits of information to each other based off of subtle postural cues and postural patterns and facial gestures and respiratory patterns and directionality of eyes and dilation of pupils, and just positioning as a person’s feet position towards the door. Are their hips positioned towards me? Are they protecting their vital organs? Are they looking away? Are they jittery? Like, that’s how we communicate.

And when we are living in a world that’s ultimately were formed by the world that we inhabit, so the modern world that we existed in large part, that structural mold that’s imprinting us, whether we like it or not, realize it or not, for the most part, if we just allow ourselves to be like dust in the wind with modernity and just allow ourselves to be formed into the modern technological mold, then what that physical, structural positioning will typically look like is going to be kind of forward head posture, hyperkyphotic spine, kind of hunched over, maybe your knees collapsing in, tension in the hips, tension in the knees, restriction in the ankles, and a generally overall collapsed chair sitting, screen staring position.

So, what that would look like if you didn’t have the story that that’s normal if you were to see maybe a small child that was stuck in that position, that hasn’t kind of been adopted into this cultural pattern? Or maybe you’re just like a primate in that position or you just took a silhouette of the person that’s inhabiting those physical, structural, postural patterns. What you would perceive information from you that you would get from that visual picture of that person would be, oh, that person is sad, maybe the person’s sick, maybe the person’s feeling defensive for some reason. They feel deflated, collapsed. And then, I know this is probably going well beyond any potential question that you had in there.

Dean Pohlman: No. That’s great.

Aaron Alexander: I’m talking, but so, then when you overlay that with statistically, what’s happening in Western culture, you and I live in the United States, and we have access culturally to the greatest health technology and innovation and health food and organic this and spirulina flakes and dehydrated kale chips and BioMats and infrared lights and cold plunges, like we had everything that the human organism possibly could at least be sold as a consumer is going to make you healthy, yet statistically, we’re gradually each year more addicted to pharmaceutical drugs of various different sorts, opiates of various different sorts. Antidepressant medication seems to just continually rise, antianxiety medication. Self-harm, suicide, all of these things are gradually going up, while our access to health or the story of health and quotations is also going up in tandem, like, what’s the disconnect there?

And I think a massive elephant in the room, which is what the function and intention of the Align Method and really, like anything that I’m really thinking about, this is the broader-like thesis of everything that I give any sh*ts about is I think that the way that we move is just this massive component to the conversation that’s understated. And that’s really the intention or function of writing the Align Method. And most of the stuff I do, that’s really the big question that I have is like, how does this movement conversation play in this broader role of health?

Dean Pohlman: Yeah. So, when you were saying that, this brought up a question for me, but I’m assuming that the cues that we give off or the nonverbal cues that we give off, that if we didn’t live in the world that we live in, the modern world that we would live in, that we do live in, then subconsciously, we would just give off the appropriate nonverbal cue or we wouldn’t think about it, we would just do it. But because we do these things with our bodies on a regular basis that our body did not evolve to do, that means that our ability to just subconsciously be human is negatively impacted. So, it sounds like there’s a balance between just our overall physical fitness and the ability to subconsciously give off appropriate body language, but then the conscious ability to being conscious of those normally subconscious…

Aaron Alexander: Yes. And the way that, in that question, holds the confusion that could exist when you are paying too much attention to yourself. When you’re going back and forth and feedback and what does this mean and what does that mean, what does this mean, what does that mean, you’re lost and confused in your physical expression, and people don’t trust you, and it feels awkward and weird. And it’s like we are self-organizing systems. Our autonomic nervous system is so darn intelligent, so your body’s more like an orchestra, a complex system in systems theory compared to like a complicated system. Complicated system is like a car or an engine. Everything is the same. Everything is repetitive. If anything goes, funky is different. It’s like, oh my god, this bad news.

The human body and the human mind, we thrive on adaptation and variability, and it’s the synchronization of the whole that really is like, that’s the expression of beauty and power and flexibility and grace. And this thing is just like, wow, like when someone walks in a room or maybe you pay to see a dancer or an actor, like a Robin Williams or someone, it’s like, wow, it’s like all of the component parts integrating into this effortless expression because that individual is organizing around some peripheral point, some external point. They’re not thinking about, okay, how am I breathing right now? Where are my eyes? Where are my hips? Where are my feet? What’s the contraction of my biceps or my pecs when you get too wrapped up in what’s happening in your own physical experience? It can be really confusing.

And so, there’s a research from a woman called Dr. Gabriele Wulf that she gets in athletics, the relation of either having and being extrinsically focused or intrinsically focused. And what she/researchers around this topic have found is that having an extrinsic focus. So, if you want to hit a golf ball and you’re focusing just on getting that ball from point A to point B, or you’re maybe throwing a punch, it’s like, okay, the cue might be to find contact to the specific point, and then your body can organize around that point as opposed to saying, okay, feel the weight into your feet, and then I want you to turn your leg in and I want you to contract your pelvic floor muscles and I want you to go through this whole-systems approach of throwing a punch. It becomes very confusing.

Dean Pohlman: Yeah.

Aaron Alexander: And so, in order to get back to a point where your body self-organizes correctly, I think sometimes, certain therapies and specific, like maybe yoga practices or rehab practices or breath practices or things that start to be really helpful. And then eventually, the goal would be to let go of all of those practices and be able to actually, finally be in the moment. And so, sometimes if a person is so disorganized as a product of like just their joints not functioning properly or having some type of impingement, you just don’t have the range of motion, say, in an ankle joint, for example, or maybe a half or something of sort, and you say, okay, cool, just do this thing. Let the body self-organize. It’s like, no, I had a block in this joint that needs to be addressed. So, it’s having the awareness and the education and the know-how to go through and have a systems joint by joint approach to get the body available to access those full ranges of motions and then forget about all of that and be able to perform.

Dean Pohlman: Yeah, I mean, that was exactly what I was feeling you were leading to. So, at one point, we may have been in alignment. Modern world has thrown us completely out of alignment. Ideally, we have no systems and we move completely in line and completely in alignment, but in order to get back to alignment, we have to use systems to get there. We have to use some sort of methodology.

Aaron Alexander: Correct. Yeah. So, systems always exist. The system might be, saying, like more an ancestral lifestyle or hunter-gatherer situation or just someone that’s more tapped into nature. They’re tapped into those various systems of nature. Sun comes up, Sun comes down, the moon, weather’s coming in. It’s maybe a little bit more humid, maybe a little bit more dry. There’s a storm coming. I’m building a fire to stay warm. Suddenly, me and my family, or friends were organizing around that fire. We’re naturally attracted to organize around that fire. The reason was because we wanted to stay warm. But now, suddenly we’re coming into this almost like ceremonial, like around the dinner table-type experience where we’re talking about our feelings and talking about stories and we’re sharing wisdom with each other. So, we’re just naturally organically organizing around, in this case, a more “natural” system.

And then if we get taken out where suddenly perhaps the systems are organizing around, maybe mess with our sleep cycles. So, now, the new system, the modern system would be now it’s just sunlight out all the time until 12:30 a.m., and you finally pull your face out of your cell phone, you put it down and you have some light-disrupted sleep pattern. There’s a bunch of lights in your room at night and then there’s some light cracking through from your window and the streetlights, or maybe you have a bunch of radiation, maybe you got your cell phone pressed up against your genitals all day long, emitting radiation and shooting out the satellites and sending information. There are a lot of different things.

Maybe your visual muscles aren’t able to go out beyond the space and the cubicle that you work at all day. So, you don’t actually get to naturally exercise those visual muscles. And maybe, it’s making you feel maybe chronically stressed. And now, suddenly, that body is starting to form into these positions. You’re sitting in a chair all day long, hunched over, all these patterns that people listen to this would already be familiar with. And now, suddenly, my body’s starting to kind of form into that position. It’s almost like the body becomes a prison in a way. I feel trapped in my body.

Dean Pohlman: Yeah. You refer to Davis’s Law in your book on this.

Aaron Alexander: Yeah, that’s correct. Yeah, exactly. Yes. So, by having any type of pressures on our bones in relation to Davis’s Law, then those bones will rebuild based upon those environmental pressures and conditions. So, right now…

Dean Pohlman: You’re literally getting strong at sitting because that’s what you do.

Aaron Alexander: Yeah. So, right now, as we’re doing this, it looks like you might be standing.

Dean Pohlman: I’m standing, but I’m standing with my feet straddled slightly because I can’t get my camera to where I want it to be.

Aaron Alexander: That’s great. Yeah, so your body’s adapted to that position. Right now, as we’re talking, I’m actually sitting. I was making fun of BioMats. I’m sitting on an infrared mat and I’m cross-legged right now. I’ll probably go through a couple of other positions as we’re doing this. And I don’t think that that’s– like I almost feel embarrassed saying that out loud because I don’t mean to say it and any like, wow, like this is so innovative or I’m special. Like, I think this is so normal, this is so ridiculously normal for you to be in an active resting position, you can call it. And if you look at once again, going back into like more ancestral existences, and it’s not about you need to be a hunter-gatherer, like a Hadza tribesman to be healthy. It’s not romanticizing any of that.

It’s taking what are the fundamental consistent principles that we can derive or pull from those cultures and our history? And how can we congruently overlay that into my modern life? Like, that’s the conversation. It’s not saying modernity is bad or chairs are bad or computers are bad or anything, it’s saying there are certain positions that act as natural self-tuning mechanisms. One of those positions, well, a variety of those positions, would be just doing really anything on the ground as you are. And then when you’re on the ground, make sure your hips are up above the height of your knees to help stabilize your balance.

Dean Pohlman: Yeah, I like that tip. That was helpful.

Aaron Alexander: And so easy. Yeah, it’s so simple. And so, in the book, I recommend at least 30 minutes a day, but ideally, it’s more than that because maybe you check your emails from– you have a floor cushion and a comfy rug, and maybe you lay on your belly for a little bit, maybe later on your side a little bit, maybe you do a straddle position, cross-legged position, 90/90 position.

Dean Pohlman: Like a kid in a kindergarten class.

Aaron Alexander: It’s so simple.

Dean Pohlman: They just lie in different positions.

Aaron Alexander: Yeah, and it’s not childish. It’s incredibly intelligent. I think the thing is when you see somebody doing– if you are living in a culture that statistically speaking as a whole is veering towards sickness, it’s not vilifying Western cultures, if you just look at statistics objectively, culturally, the ship is going towards greater amounts of sickness. It’d be hard to argue that. There are lots of beautiful things, lots of intelligence, lots of sweetness, lots of love, all the things. But from that lens, it’s like, oh, interesting, we’re going in a funny direction. And you live in that culture for you to do something live in a way that is inherently, consistently, health-inducing will look funny. And that’s the thing, it’s like being okay with being at a bus stop and doing what any person in Thailand would do, they’d pop a squat.

Dean Pohlman: Yeah.

Aaron Alexander: Or any person in any culture that doesn’t suffer from losing billions of dollars each year to surgeries in relation to osteoarthritis, and medications. It’s like orthopedic surgery is such a massive industry in the United States and it’s preventable. You just need to look a little different. And what that’s going to look like is doing essentially what people might deem to be like, oh, it looks kind of like you’re doing yoga. It’s like, no, no, no, it’s not yoga. I’m doing human. This is human.

Dean Pohlman: Doing human. That’s what I’m going to tell people when I’m out in public. Marisa has gotten used to this. My wife has gotten used to this entirely. But when we go out in public, I will just do random stretches. I’m like, yeah, my back’s feeling a little stiff. I’m just going to hold a lunge for a while, or if I’m in line at the grocery store, I’m like, I’m going to work on my balance or I’m going to do some side bends. So, people would see that as weird. I see that as like, well, logically, I have nothing else to do in this moment, so I might as well do something to make my body feel better.

Aaron Alexander: The movement that you naturally would engage with in order to gather food or water or create some shelter or build a fire or any of that stuff, take care of your kids, as opposed to having someone else take care of your kids and you make lots of money on your computer while you sit in that same position and you specialize as a sitter, you have a specialized computer sitter. Very important. Very fancy car.

Dean Pohlman: What if that’s what job descriptions were written like?

Aaron Alexander: I mean, if you were to write job descriptions from a mechanical perspective, for the most part, it would be prestigious sitter.

Dean Pohlman: Yeah.

Aaron Alexander: Like I sit more prestigiously than…

Dean Pohlman: That’s a huge perspective.

Aaron Alexander: Yeah. Like, objectively, again, like get out of the stories and narratives of I’m better than you or worse than you or higher up in the socioeconomics, like what do you actually do? If you’re honest, for the most part, it’s like I’m a professional stander in place, sitter in place, repeat.

Dean Pohlman: Yeah. I mean, this conversation alone and me reading the book, this just reveals to me just how much you think about movement. Like, I think about what I’m doing when I’m sitting and looking at the computer. I don’t think about the position that I’m in. But the main way you’re looking at this, at least in this conversation, is what are you doing with your body, not what are you doing with your fingers and your eyes, but like, what’s your body doing? It’s an interesting perspective. I mean this is…

Aaron Alexander: It’s all connected.

Dean Pohlman: So, I’m really glad you brought up the sitting practices because I know that when I’m sitting more, I feel better, my hips feel a lot better, my back feels better. I like working on the floor. But the struggle here is, is I also live with other people. I have a couch. My wife’s not going to want to get rid of the couch.

Aaron Alexander: I have a couch too.

Dean Pohlman: Oh, you do. Awesome.

Aaron Alexander: My knee is touching the edge of the couch right now as I’m sitting on the BioMat on the floor.

Dean Pohlman: That’s what a couch is for, your knee is supposed to rest on the edge of the couch. You sit on the floor.

Aaron Alexander: No, I lie on the couch. The couch is right in front of a TV. I’ve got surround sound. It’s a normal house. We watch Netflix. I watch stupid, whatever, comedies and stuff like that. You would not walk into my place and be like, oh my God, this is a crazy part. It’s like…

Dean Pohlman: I thought you had monkey bars, for sure. I thought you had monkey bars.

Aaron Alexander: I have a pull-up bar in the doorway to my bathroom.

Dean Pohlman: Yeah, see, I got it.

Aaron Alexander: Yeah, super simple.

Dean Pohlman: Yeah. So, my question here is how would you recommend to start a floor practice?

Aaron Alexander: Just make it comfortable.

Dean Pohlman: Make it comfortable.

Aaron Alexander: Yeah, make it comfortable. Don’t make it weird. Like sometimes, something that I’ll notice people that are, I don’t know, maybe like emulating perhaps some of the stuff that has maybe come from like these ideas or maybe they specifically got it from Align Method stuff or maybe they didn’t or whatever. But oftentimes, what I see is it’s like it looks so goofy sometimes. And I’m like this doesn’t need to be goofy, like it can be told, like, you can have the house be totally funk straight out and have nice things and have anybody come in and say, man, this place feels so great, it feels comfortable.

And I think that if you go to a lot of different cultures and a lot of like really interior design and architecture that I prefer and I enjoy does have some of that kind of like bohemian kind of vibe, or if you go to Morocco or maybe you go to Japan or maybe you go to, I mean, those would be good examples to start from, it feels comfortable, like you come into the place, and it’s like, oh man, it’s like lots of soft fabrics and nice, earthy colors and maybe like a shag rug. It’s like inviting to come down onto, like it should be inviting. It shouldn’t be like, oh, cool, I’m an Align Method devotee. And so, if you walk into my house, it’s just hardwood floor and a yoga mat and a candle. It’s like, no, no, like, don’t do that. Do that maybe for like a retreat and release all things and do some esthetic, darkness retreat or vipassana or something where you’re like– yeah, like, I can let go of everything like that. We have that gear as well. And if you want a girlfriend, it’d probably make your place comfortable.

Dean Pohlman: Yeah, I’m still getting over the shock that you have a TV and a couch in your living space. So, thanks for giving me some time to process that.

Aaron Alexander: I have a car. I have an electric bike, so it’s like pedal-assisted electric bike.

Dean Pohlman: Do you still have the car that’s way too small for you?

Aaron Alexander: No, I got an SUV.

Dean Pohlman: Okay. Did you have a Prius?

Aaron Alexander: Yeah, in L.A., I had a Sporty Prius, yeah.

Dean Pohlman: Yeah, just for reference, you’re 6’4.

Aaron Alexander: Just around 6’5.

Dean Pohlman: Okay, so you’re super tall. And just in general, Aaron takes up a lot of space with his aura and also, with his body.

Aaron Alexander: Obnoxious.

Dean Pohlman: Obnoxiously lovable.

Aaron Alexander: I appreciate. You’re very kind.

Dean Pohlman: I’ll say. Okay, so that’s helpful for me. So, just make things comfortable. And that’s simple. Here’s one thing I’m thinking about. So, outside of the context of this book, a lot of these practices just seem right, even though they seem normal in terms of looking at basic movement and if we look at movement before modern time, a lot of this does seem weird to normal people outside of the context. So, I’m wondering, how can we make some of this stuff less weird? Like how do we go from people who currently don’t have any of these practices in their life to adding three, four, or five of these practices on a daily basis?

Aaron Alexander: I think really, the only potential I’ve reached at all is the suggestion to spend more time on the ground, which again, if you really break it down logically, it’s not really much of an ask or reach at all. If you ever do any yoga class or martial arts class or maybe dance class or anything where you’re doing kind of like meaningful things with your body, you’re already just organically getting a lot of that floor time in those positions. So, I’m just saying, “Hey, why not just integrate that into your home life?” It’s not a big deal.

And then the other things that I recommend in the book, there’s nothing in it that’s strange. It’s educating people on how to leverage their breathing patterns to either upregulate, feel more stimulated, cognitive, clear, awake or to downregulate, calm down, rest, digest, restore, all those things. So, just understanding that your body, you’ve been endowed with a whole plethora of different toggles and levers, and we call them your senses. And you can pull these different levers or these different senses if you understand how to drive them, how to operate them, to make you feel different ways.

People have been doing that with psychedelics for years. It’s like, cool. We know we have this technology. That mushroom does that. That moldy ergot stuff does that. That cannabis stuff does that. This is, again, not weird. This is biblical. This is any culture across the planet that does some type of mind-altering substance, and if they don’t have access to those substances, then they’ll do what’s called ordeal poisoning, which it’ll be either starving themselves or maybe going through some type of like pain-related ceremony or something to alter their state. That’s what humans do. Creatures do it as well, like if you are a sentient being, it’s interesting for you to alter your state.

We can do that. Breathwork practices are an obvious one, holotropic breathing, things of the sort through my meditation. But then, that’s further into the spectrum of altering your consciousness with breath. But then what about just like day to day? As I’m sitting here having this conversation, there are things that I could do to keep my nervous system and more of like a calm state. There are things that I could do to say before, say, I was really nervous to do this podcast, and I’m like, ah, hyperventilating, oh my God, I don’t want you to judge me. I’m freaking out. And so, I can feel myself kind of going into that hyperventilatory type of breathing pattern, almost, maybe I have noticed myself mouth breathing. Maybe it’s hard to get a full exhalation. I feel like there’s a resistance of my exhalation, so I can say, okay, wait, I know, I know what I can do here.

I could do what I read in the Align Method or lots of other books, but Align Method is not the first book to talk about breath, I mean. You know what? I can emphasize a long exhalation. I’m going to bring my breath back into my nose and I’m going to slow that breath down, create three times more resistance through breathing through my nose and through my mouth sort to activate these diaphragmatic muscles, an ascending indication to my autonomic nervous system that I feel calm. So, you can mechanically move your body to feel a certain way and you’re recommending…

Dean Pohlman: In your book, you write about a four-four-six-four. That’s the cadence you used.

Aaron Alexander: Yes, like a spin-off of box breathing with an emphasis on the exhalation if you want to calm down. So, when you’re, ah, that’s yoga stuff again, man. Like, what is, oh? It’s a long-as* exhalation and audible exhalation. And then how do you feel, oh, my God, I feel so spiritual, like samadhi, bro. It’s like, dude, this is physiology. So, whatever overlay you want to put on it, you can put it Western anatomical kind of scientific speak, you can put spiritual. It doesn’t matter. There are consistent truths in every medium or every kind of language of physicality.

Dean Pohlman: Yeah, that kind of brings up the question of how people experience spirituality because it always made me kind of confused, and I would go into a yoga studio and do a workout, and someone would describe it as spiritual because I come at it from the fitness background where to me, it’s like, okay, we just did a workout. Yes, I feel good, but I don’t know if I consider it a spiritual experience. Anyway, it’s kind of interesting to me that for yogis who might not have the fitness background that I do, they experience movement, as they kind of classify it as spiritual. I wouldn’t say that it’s spiritual, but in reality, we’re feeling those endorphins, we’re feeling connected to ourselves, we’re being in the present. So, we’re describing in different ways.

Aaron Alexander: So, like, Alan Watts said the biggest ego trip is dropping your ego or some language like that, cutting off your ego or releasing your ego or whatever. If you’re going in, like that’s egoic. Like the idea of, okay, this is spiritual, this is not spiritual. It’s like, if you’re that person, then I think you’re missing the reality that everything is pretty darn spiritual, and also the reality, it’s just a story, it’s a narrative. What does spiritual mean? It’s subjective. And I think that there is inherently a limitation if you’re excessively science-based because science is just another religion. Science is just another viewpoint. Science is not the law. There are some things that are pretty darn consistent in science. They seem pretty darn true, like gravity, 9.8 meters per second square. Pretty consistently, you drop a ball, it does that, but that’s just measuring and observing a pattern, an observable pattern, with the instruments that we’re observing it through.

Our consciousness is an instrument to observe this experience, and perhaps we have the availability to observe and leverage that instrument in different ways than what, say, like most college curriculums would provide us with, where it’s mostly governed by science in Western anatomical speak. So, I think that there is something to those other more like Eastern esoteric kind of metaphysical conversations that if your mind is just completely saturated in Western anatomical science-based evidence, there perhaps could be a limitation there. There’s like that the etching, it says something like if you only see the five colors, then you’re blind. If you only hear the five tones, then you’re deaf. And actually, I don’t even know if there are five tones, but whatever.

If you just hear these tones that we kind of accept as being sound, then you’re deaf. If you just see the colors we accept as being colors, you’re blind because the reality, that’s a small percentage. We hear a small percentage of the acoustic spectrum. We see a small percentage of the visual spectrum. I would suggest that in any of our senses, we have the potential to be opened up to perceiving more than what we’re taught for the most part if you go through like traditional Western school.

Dean Pohlman: Yeah. I mean, that makes sense to me. So, I want to change gears a little bit. I want to ask you a little bit more stuff about you personally. So, I’ve done squats with Aaron, and his mobility is just really good. His mobility is ridiculous. Way better than mine, I will say his. If you look at the photos in the Align Method, his shoulder mobility is incredible. You’re just very flexible. And I’m curious, have you always been flexible? Have you been inclined to be flexible? What is it? What’s been so helpful for you increasing your flexibility?

Aaron Alexander: I used to be really much more, I don’t know if I was like super stiff, but…

Dean Pohlman: You were swole.

Aaron Alexander: Yeah, I was more swole. I have these postural archetypes that are in the Align Method book. And yeah, so I was really obsessed with bodybuilding and just being bigger, just want to be bigger. And so, during that time frame, essentially for me, it’s like 13 to 20. No, I wasn’t flexible by any means. And then I moved to Hawaii, started getting more into surfing and started training jujitsu and just different things that kind of started to open, I think, my mind and body, just the way I was thinking, the way I was moving, and the things that I cared about and became less about just getting jacked and tan and swole and more about like skill acquisition and adaptability and speed and things of the sort. And then I got into yoga. I’ve been kind of like enamored by a lot of different mediums of physicality. And yeah, so this flexibility stuff, I start paying attention more to that doing like jujitsu. And so, that maybe started like 14 years ago or something. But before that, I wasn’t stretchy.

Dean Pohlman: Cool. Yeah. When we did hang out, we went to Zilker, and you were trying to teach me, I forgot, you were trying to teach me some sort of flip, some sort of side flip, jumpy side flip-type deal. And it was striking to me how difficult it was for me to do something that was unstructured because so much of what you know, I’m doing yoga a lot, I’m doing weight training now. I’m recording yoga classes, and so much of what I’m doing there is like, this is where your arm goes, this is where your knee goes, this is where your hips go. And that’s good in the sense that we all have these basic movement patterns that we should work on that just help us with full-body strength flexibility, but also, the absence of a lack of structure is also not beneficial, like that lack of structure is great for just helping. So, I’m wondering if you can speak to kind of that the benefit of lacking structure and exercise because I’ve seen you do a lot of that stuff.

Aaron Alexander: You create structure to create freedom. If you are obsessed with structure and rigidity and you you miss the opportunity for freedom, like you come to a Y in the road, you say, okay, I think I have the structure to be safe and freedom. And you say, I’m going to go deeper into structure, and then you maybe are presented that Y again and you said deeper structure and presented that Y again, deeper rigidity, presented that Y again. Eventually, that Y in the road, that fork in the road kind of stops presenting itself. And you’re like, now I’ve kind of painted myself into a corner where I’m so mechanistic with the way that I move that I haven’t really trained any form of play or improvisation or complex problem-solving. All I’ve done is essentially overlaid, it’s kind of like Western education, like Scantron teaching to the test physicality.

Dean Pohlman: I forgot about Scantron for a good three years. Thank you for reminding me of that.

Aaron Alexander: I had to bring it back. I don’t even know they still exist. I imagine they have to. And that’s the thing is if you educate a person to be a Scantron test taker, teach the test, they may present as though they are incredibly intelligent, but they probably will never have much in the way of meaningful innovation because they haven’t constructed that play muscle and that improvisation muscle and that problem-solving muscle, their problem solving is memorize this position, regurgitate here, memorize, regurgitate, memorize, regurgitate. So, that can be valuable as a foundation. And then from there, you have to write essays and you have to critically think and you have to allow your mind to bend and allow your body to bend. And that’s when you get like an Adesanya in the UFC or like a kind of McGregor or any fighter, they’re unpredictable and incredibly dangerous. And that’s what I think most dudes at least would probably prefer.

There’s some kind of sexy about that, maybe big girls would prefer that and maybe their own way or in a different way, but like, that’s the thing is being able to say, okay, Bruce Lee, be like water, whatever the equation that comes, the foundations of the way that I move, and ultimately, where they think because movement is just thinking expressed through physicality, that’s what it is, then I’m able to quickly adapt to that in a safe fashion because I have those structured fundamentals so deeply just driven into my nervous system, and I’m adaptable and flexible enough to interpret that information, split-second, boom, self-organized response, no thinking, no problem solving, just bah, and that’s a product of East, West, Western anatomical structure, linear foundation, all that. And then I’m saying east-west is like a metaphor. We can say the east is more like the kind of aqueous, free flow, creative ethereal part. I’m able to be in that aspect and I also have that foundation of structure.

Dean Pohlman: Yeah. I mean, you kind of fled right into what I was going to reiterate based on what I thought you were going. So, I don’t think I even need to say anything other than, once again, emphasizing that connection between movement, how we move and how we think, and how just kind of that line, they just kind of work in tandem.

Aaron Alexander: Yeah, movement is thinking, like I think that’s an interesting thing to stew on, and it’s like interesting. And there’s deeper, maybe not deeper, but your body can also think without the brain, like you can move without the brain. There’s myoblast. And yeah, in the spine, there’s what’s called central pattern generators that essentially, if you start walking, then your spine has neurons that automate that walking pattern. So, this is done in the equestrian, a lot of this research comes from the equestrian world working with horses, but you can see that with dogs. If you put a dog above water, they’ll just dot, dot, dot, dot, dot, dot, dot, dot, just like there’s some deeper intelligence there that the dogs are ya, ya, ya, it’s like two systems.

Dean Pohlman: I’m going to YouTube that later.

Aaron Alexander: Yeah, look up central pattern generator.

Dean Pohlman: Yes.

Aaron Alexander: And the same thing, your fascial tissue has contractile cells to be able to respond to stimulus.

Dean Pohlman: I tried that face-searching thing in the book.

Aaron Alexander: It looks so weird, but it’s actually very nice.

Dean Pohlman: Yeah. If you’re watching me right now, this is what it looks like, something like that.

Aaron Alexander: Your facial gestures, yeah, I mean, what you did there, like you’re looking up with your eyes, that’s all, again, yoga stuff. A lot of the really weird stuff that you do in some yoga class, again, there’s a Western explanation.

Dean Pohlman: Lion’s breath?

Aaron Alexander: Oh yeah.

Dean Pohlman: That’s right.

Aaron Alexander: Yeah, opening up, they mean that like Tom Myers, the Anatomy Trains is his creation, and he, among other people, but he’s done a really good job outlining the continuity of the tissue around the tongue and the throat down into the heart, the pericardium, the diaphragm, psoas, the pelvic floor, and adductor, and all the way down, like there’s continuity of connective tissue all throughout the body. So, that tongue, that deep front line, if you’re bound up in around your throat, in around your tongue, that could be associated with issues that you might be experiencing elsewhere.

So, to open up, think of if you’re getting a massage or you’re doing your own mobility practice or whatever, who differentiated what is a viable muscle to work with and what’s not, it’s kind of crazy to think, okay, cool, like biceps, pecs, delts, adductors, hammies, those are appropriate locations to work with, but throat, tongue, eyes, mandible, masseter, all these other kind of like forgotten tissues, pelvic floor muscles, like your prostate, if you’re a man, like all of these tissues, they’re viable, and even saying, like working with the prostate, people would be like, oh, it’s like, that’s so funny.

It’s like prostate cancer is not that funny. And so, starting to open up a conversation around, huh, could there be a manual conversation like a movement conversation around getting old, dysfunctional, backed-up fluids and tissues, not necessarily dysfunctional fluids, but old fluids, circulate that old stuff out to replenish with the new? Is there a movement conversation in that in any and every tissue in your body? The answer is absolutely, yes.

Dean Pohlman: Yeah, well, then we would have to face the obvious reality that fitness is, so we look good on the outside and not as much, though, is by most people in practice for internal well-being.

Aaron Alexander: Yeah, looking good is a byproduct of internal well-being. You can put lipstick on a pig, but there’s something special about someone that, Charles Bukowski calls it a free soul. Someone is like, they make you feel away when you’re around them. You can’t really explain exactly what it is, but when you’re around a free soul, it makes you feel good. And that person that has that, again, this is getting like yoga talk, like sensation of like liberation. And that’s what a lot of people are seeking, perhaps. They’re in like a yoga kind of spiritual-type space, which if you’re seeking liberation, you’re already creating a separation between you in it. So, the carrot will just keep on being pushed forward, but yeah, it’s important.

Dean Pohlman: Cool. So play, talk about the importance of play, talk about the importance of sitting. How can people start? Like, let’s just assume that I don’t have any sort of play practice. What are some easy things that I can do? Or what are some ways that I can start implementing a daily play practice?

Aaron Alexander: Play practice already kind of neuters the whole thing and like, sterilize it. Sit, so…

Dean Pohlman: So, don’t call it practice?

Aaron Alexander: No, call it if you want. But so, as long as you perceive practice is play, which that’s cool, if you do, that means you’re probably a pretty evolved coach if you can overlay that play element. Hopefully, this conversation is play. Hopefully, you hanging out with your girlfriend, you working, you’re creating a program, you’re writing a book. Hopefully, it’s this sensation of like, wow, this is like organic kind of almost effortless flow state. If people are ever in that state, it just feels almost like you’re playing an instrument or you’re being played. And so, yeah, you could practice play, and it’d still be fine. But for the most part, if it’s like you’re grabbing yourself by the neck or by the collar and you’re like, okay, we’re going to practice play, it’s oh, you’re practicing play again. It’s more like finding that organic spontaneity, it’s very nice.

Dean Pohlman: And it’s going to be different for everybody.

Aaron Alexander: Yeah, and sometimes you might need to practice play in order to get lost in play, and that’s kind of the thing, like that structure. Sometimes, you got to kind of push the rock up the hill in order to get to the point where it can kind of gain momentum and roll down the other side. So, with that, it’s like, yeah, sure, practice play, but ideally, it’s get lost in the experience and acknowledge and recognize that that potentially could be the end for the most part, like the entirety of a person’s life if they’re really doing the life thing. I don’t know. Masterfully, maybe, maybe I feel like I’m bordering on sounding kind of overly poetic or pretentious, but if you can be in that place with the way that you live, it’s pretty cool.

And so, why does play matter? Play is, one, it happens all throughout nature. Ants play, dolphins play, primates play, like all sorts of different creatures. If you look at them close enough, long enough, they’re like, I think those little mofos are just playing right now. It’s like, why is that? So, it’s probably not helping them have sex more or fight better, and as far as immediate value, it’s like a real liability. If you’re playing, you’re essentially and you’re like a creature in the woods and you’re making noise and you’re running around and you’re like laughing. Mice laugh. That’s actually a real thing. They giggle, laugh. Jaak Panksepp, this guy kind of went getting all that stuff. I referenced in the book.

That’s a huge liability. Like, you’re presenting yourself to be hunted at that point. You’re wasting time. You should be building shelter. You should be having sex. You should be fighting off predators and potential, like other creatures that could be invading your territory. You should be training, but these creatures freak and play a lot. And so, what’s happening in there is you organically are training and you organically are flirting and you organically are understanding how to be socially effective. Okay, I push the boundaries too much. Okay, I didn’t push him enough, now I’m boring, I didn’t challenge this person’s belief systems or challenged this person’s athletic ability. I got to push more. Oh, I pushed you hard. Oh, they punched me in the face. They got mad when I did that. Like that rough and tumble play is absolutely invaluable to educate a child or an adult, for that matter, how to effectively show up in culture.

Dean Pohlman: And hence why BJJ must be so popular.

Aaron Alexander: Well, yeah, I mean, a lot of things to that, but yeah, it’s a lot of play there and a lot of human contact. There’s a whole chapter in the Align Method book about touch, the power of touch as well, just a small little bit. Well, one, play stuff, Jaak Panksepp’s stuff. He is like a world-leading researcher on conversation around play, how it affects the brain/whole body. And some of the research that I referenced to him in the book is they specifically were observing 1,200 different types of genes and found that just 30 minutes of movement-based play each day affected the expression of over a third of those genes.

So, as you are in a positive direction, it’s like, oh, like, cool, that’s good. And so, that practice of playing, it’s not just something that it does innately make you better at pretty much everything. It does help with creative problem solving and it also literally changes you at a genetic level. And so, it’s like if there was some type of super-food supplement or something to take you out of, maybe say more of like an isolated, depressed-type state, like a disassociated, disconnected-type state, or to just make you feel less anxious, make you be a better problem solver, make you more creative, make you feel like there’s a freakin purpose to being here, play would be it. There’s nothing that trumps that. So, I think it’s again kind of like who I described in the book, a lot of these movement patterns that I recommend that are inherent to humanity since forever, they act as tuning mechanisms for the mind and body. Play is one of those.

Dean Pohlman: Yeah. So, for me, that brings up a struggle that I have with a lot of these things that are, let’s just say they’re good for you. Let’s just sum it up as like these things that are good for you, but only if you immerse yourself in the activity for its intrinsic benefits. Not so much as like your, oh, I’ve got to play again, got to do it because I know it’s good for me. So, my struggle is okay, like, I need to live in the present. So, I’m going to live in the present. Okay, I’m living in the present, this is good for me. Yeah, but I’m not living in the present because I’m looking at it as like, it’s a productive activity that’s going to help me be more productive, so.

Aaron Alexander: I mean, there are a few different angles. One, the big thing is listening to your body, so your body has an abundance of information that it’s continually feeding to you throughout the day, like your vagus nerve, 70% of the nerve pathways are afferent, meaning they’re feeding information from your viscera, from your organs and your body up into your brain. There’s 30% that are efferent, they’re sending information down, a large percentage of the information going from your heart, or similar concept with information going heart to the brain. Like your body is sending a lot of information up to what we think to be the dean of all of the things being your brain.

And so, when you’re in a scenario, maybe you’re at a job that makes you feel a way to check in. When I walk into the office or whatever, like, how does my body feel? How’s my stomach feel? How do my shoulders feel? How’s my jaw feel? Like have a moment and say, like, how does my body feel right now when I’m here? When you’re with a certain type of person, when you’re with your friends, with your girlfriend, with your boyfriend, when you’re in certain environments, I bet there are some environmental conditions, maybe in nature, like an easy example, because nature is really emotive for humans. So, how do you feel when you’re around mountains? How do you feel when you’re around an ocean? How do you feel when you’re around rivers? How do you feel when you’re in a city? How do you feel when you’re in a subway? And just start to listen to say, like, what is my body telling me? And say, okay, cool, like message received, I’m not going to keep putting you.

Every time I’m around that person or that job or whatever, I feel this dark, collapsed kind of just like achy way. I feel like I’m trapped inside of my body when I’m around that, could be an indication that they are a healthy trigger of sorts for you to observe and look at and say, what is it about this person? What can I learn more about this? How can I go deeper into this and gather the information? And it could also be an indication that’s cool, learned the lesson from this. The lesson is I don’t need to be around this. Change it. And then from there, ideally, throughout your day, you walk into your home and maybe you hired an interior designer. You found intelligence, like I think girls and gay guys are usually really good with designing things typically.

For me, like, I always have a girl that’s historically, if I ever have anything that looks nice, it’s because there’s been an influence from a girl. There’s like this feminine touch of like, oh, wow, like, it feels soft and it feels colorful and it feels balanced, like, wow. That makes me feel a way when I come into that space. How does your car make you feel? Just starting to pay attention to that and then start to reorient things based off of the way that your body feels and what you’ll find if you do that and you start concentrating more. A higher percentage of your day with those places, persons, things, conditions that make your body feel open, make your body feel creative, make your body feel expansive, make your body feel any of that stuff, your life will improve.

Dean Pohlman: So, what you’ve been talking about for the last few minutes, it brings up, one of the things I wanted to ask you about is an Instagram post from November 1, 2020. “I’ve been in large part, a closed-off robot for the last decade or so when it comes to any level emotional intimacy involving my own heart.” And that really resonated with me because I had to unlearn a lot of kind of the emotional walls that I put up for myself as a child. Not that I went through anything terrible or any sort of significant trauma compared to what a lot of people go through, but just things that made it so that I was more closed off.

And so, as someone who also has gone through what it sounds like, you’re kind of you’ve gone through, I’m just curious if you want to speak at all to the changes that you’ve, at least recognizing the kind of the barriers that you had it for yourself and maybe some things how you’ve gone about addressing that or some things that you’ve realized that just kind of fit in with what we’ve been talking about.

Aaron Alexander: Yeah. Well, the first interesting thing that I hear in that is the idea of like, I haven’t gone through this or that or like comparing someone’s trauma or all of that stuff to somebody else’s or, one, like asking the question, if you don’t think that you have gone through anything that might augment your capacity to feel safe with love, for example, or some of those things that make especially like men, feel like, oh, this is getting a little scary, both men and women, but men might have a little bit of a tendency of running away. Actually, that’s kind of both ways. But the interesting thing with the idea of like, I is like, you are not you, you are a continuation of your parents, and your parents are a continuation of your grandparents, and your grandparents are a continuation of your great grandparents. And all of that is informing the structure and function and physiology and the manner in which you’re wrapped.

And so, the idea of like you, you were a complete absolute continuation of all of your history. And now, the ball’s in your court. But the score of the game, that wasn’t up to you. You just got put in the game, right? So, you could have got dropped into the game, and your ancestral history team could have been up nine to one, you could have gotten dropped into the game, you could have been down 1 to 12. And it’s like, well, I, in this time, my time on the field, I have and it’s like, there’s no you, like you are a continuation of the past and you have the potential in this present moment to make it maybe like a more spacious, easy, comfortable go for your future kids. So, that idea of like I, I think, is really interesting in the first place. Does that make sense? Does that sound like some new age?

Dean Pohlman: No. I mean, I think that…

Aaron Alexander: And I know I didn’t answer the question, but that’s just an interesting thing of the idea of I.

Dean Pohlman: No, I think that we use the term I or we use the term you when we’re speaking about a general situation and I think subconsciously, we might use one or the other. But I guess my reason for saying that is to, well, one, I’m trying to be sensitive to the fact that I haven’t gone through trauma, that’s seemingly as, I mean, that’s not as significant of people who have had significant violent past or something terrible happened to them. In another way, it’s also downplaying the legitimacy of the things that I’ve gone through as a way of devaluing the necessity of dealing with some of that trauma, I think.

Aaron Alexander: Oh yeah, man. Yeah, I mean, typically like me working with– so I have a background of working with clients, doing Rolfing and various different forms of manual therapy, structural integration being like one of the primary ones, but just working with people’s bodies via training and hands-on therapy. And what I’ve found to be pretty darn consistent is the people that think that they have the least to work on often times have the most to work on.

Dean Pohlman: People who don’t need therapy need it the most.

Aaron Alexander: Yeah, I’m not projecting that on you, but just as a general, consistent pattern that I’ve gathered from people where they kind of come in, and their wife demanded that they come in to see me or something like that. I’m like, hey, Bob, like what’s going on? It’s like, oh, you know I’m pretty fine. I think things are pretty good. Wife told me, you got a command, you’re pretty good. And I’m like, okay, and it’s like, okay, there’s like a laundry list that Bob’s just hasn’t had the resources or tools or interest to really start to unpack. He doesn’t need to unpack it, whatever, he doesn’t. You’ve, depending on your belief system, like lots and lots of lifetimes, maybe, or whatever. Who cares? It doesn’t matter. Like, whatever happens is perfect, I think. You don’t need to do anything, but there’s the opportunity to do whatever you have access to.

But that person that feels like they don’t have a lot going on there oftentimes, they just haven’t had the tools endowed to them or haven’t stumbled into the tools to be able to start to kind of purge some of those resistances or maybe fears or shames or like deeply held contractions or inhibitions. And they just never got the the tools in order to kind of allow that stuff to get out. So, they’ve kind of built around this sturdy kind of like hard container. I know that I’m speaking very kind of like esoterically right now, but I mean, that’s something that I’ve consistently seen with a lot of people, a lot of people that come in with a laundry list of like all of the specific things. And I’ve got this neat thing and this hip thing and shoulder thing. And I can’t get my internal rotations, like 42 degrees, I’d really like to get it to 45. That person’s like dude, your body is just– you’re killing the game, you might be paying too much attention and creating issues out of nothing.

So, there’s a balance of feeling almost like numb in our bodies and the kind of a sensation of like, I think, it’s fine. And then there’s the other side of the balance of, I feel too much and I’m creating issues out of something like, I am actually responsible. I’m like the progenitor of the issue, like the way that I operate is I am always seeking issues. I don’t think I responded appropriately to that, but.

Dean Pohlman: I’ll ask you again. But what was striking in the response was, you so fluidly transitioned from talking about emotional trauma to physical, and there wasn’t even a transition, you’re just this is the one and the same, and that’s that. And that was interesting to me. Just for you to be that is so present in your mind, that’s just the way that you think so much that there wasn’t even like an explanation to the transition. You just immediately went body, also emotion like flawlessly.

Aaron Alexander: Yeah, your body’s like a chapter book. So, if any time, like an example would be say you rolled your ankle, or if you roll your ankle, we could see you rolled your ankle, like you didn’t roll your ankle and then suddenly like it has gone. We can’t say you’re limping for some reason. Say, maybe you had like an emotional ankle roll kind of situation where maybe you came home and I don’t know, your dad was abusive to your mom or something, and that’s like this sensation of, I’m afraid, maybe I want to cry, maybe I want to fight, maybe I want to, ah, uh, but I don’t have the resources to do anything about this, so I’ll just kind of swallow this. It’s not safe to cry so I feel like this diaphragmatic contraction that, oh, oh, oh, like, I’m sucking at that emoting up and swallowing it back down. And then I move forward. I say, everything’s fine, everything’s fine, everything’s fine.

Dean Pohlman: I was really good at that for a while.

Aaron Alexander: Yeah.

Dean Pohlman: Still good at it, unfortunately.

Aaron Alexander: I mean, my guess based off of like what you’re saying is there’s some of that for you to explore if you so choose to do, would be might just like my guess. And for, I think, anybody, especially men, like to learn that is…

Dean Pohlman: I did want to ask you about your specific experience with that.

Aaron Alexander: Yeah, sure.

Dean Pohlman: What were some practices or some just things that you uncover that you feel comfortable sharing, or maybe just the practices that you kind of utilize to help with opening yourself up?

Aaron Alexander: I think I still have so much work to do. I think that I’m so well. Yeah, I’m like very much in process. So, it feels kind of almost inauthentic for me to be like, well, this is what you do. I am like also a hot mess, just like anybody. And that’s the thing that makes us, we have that in common. Most people, we’re like adults or children wearing adult costumes.

Dean Pohlman: Or children in adult bodies, absolutely.

Aaron Alexander: And we’re all be kind for everyone is fighting a great battle. I don’t know who said that, but that’s like if you’re in a physical form, you probably have a lot of internal twists and turns and resistances and shames and fears and love and joy and art, like you’re all of it. And so, some of the stuff that has been helpful for me to kind of start to maybe like disarm would be placing myself into situations that are incredibly safe to be incredibly vulnerable. I’m placing myself around people that exhibit that and model that and aren’t just a bunch of weak, kind of like unstable-type people, but it’s like, oh, no, you’re strong and you’re strong through your vulnerability.

Like that, to me, I think, and especially for men in general, like being able to find that, I’m happy to be able to say that I have several friends that stand out like that, that it’s like if there was ever any type of physical confrontation, you literally would win the confrontation with 99.99% of humans on the planet. And you’re incredibly tapped into your emotions and vulnerability and you will cry and hug and love and express when you’re afraid, and that’s just like, wow. So, having exposure to that, I think, is really invaluable.

Dean Pohlman: Do you feel drawn to those types of people?

Aaron Alexander: Yeah, for sure. Yeah, yeah, when people are just stuck up and being like a dudebro, it’s fine. I mean that sometimes, dude brothers are really funny, or they can be helpful in certain things or like, I can appreciate that part of them. But as far as the people that are the inner cabinet kind of people’s like, oh, you’re like my brother or sister or whatever, typically, is that person.

Dean Pohlman: Yeah, not so much like you’re choosing to hang out with one guy or to hang out with this other guy, but you just feel like a pole, you feel like a natural inclination to spend more time, kind of like you were discussing earlier. If you’re with a certain person or you’re in a certain situation where it just feels like darkness is enclosing you versus you’re with other people…

Aaron Alexander: And that could be you, like that’s the important thing is if you run away from every time that you have an internal anxiety or internal contraction or resistance or any of those sensations, your heart rate starts to go up, oh, like okay, right away, you could just be re-perpetuating the same pattern of being of whatever, victim or running away or whatever the thing is. It’s like there is also the potential that you could start to change the script up and say, oh, those are the things, actually, from a sovereign, empowered way, I seek those out.

Dean Pohlman: So, those situations that you’re feeling uncomfortable in, those are the ones that you feel uncomfortable, but another part of you feels this is what I need to explore, this is what I need to kind of draw myself into because it’s making me feel, it’s that sense of discomfort that says this is scary, this is new, but I also feel drawn toward it because I know I’m going to feel better if I can do it.

Aaron Alexander: Yeah, exactly. For the most part, if you live a life where you just feel “good” all the time, it’s probably a pretty boring life. For the most part, the cave you fear to enter holds the treasure you seek. It’s a Joseph Campbell quote. And if you’re going to enter caves that you fear, it may also be wise to have a good resource group and bring a flashlight and tell somebody on another line, say, “Hey, close friend, whatever, like at three o’clock p.m., Tuesday, the 12th, I went into this cave. If I don’t come out, please send help.”

Dean Pohlman: Yeah. Well, I think your answer of finding strong friends, finding situations where you can be emotionally vulnerable, I love that because it’s practical, it’s like I can, okay, I know what to look for. So, that’s really cool. So, thank you. Last big question I want to ask you, what do you think is the biggest challenge facing men and their well-being in today’s world?

Aaron Alexander: Men.

Dean Pohlman: I know, men in particular.

Aaron Alexander: I think probably all the stuff we talked about, probably like the idea, I think both men and women, there’s been a cultural push. I just did a podcast that went out a handful of days ago. I was with my friend Chris Williamson, and in the conversation, we were talking about, he was talking about largely, but how men and women have been influenced to express what culture to be accepted is like masculine tendencies. So, be strong, conquer, be organized, build the empire. He’s English. He said, boss b*tches clapping back. Girls are like, got to be a boss babe. You got to be able to get in the boardroom, handle your sh*t. There are lots of other fish in the sea, dump her, get on hinge, and just run through, like keep going, knock walls down.

I think that story for men and women is if that’s your story and you don’t also have access to, whether you have a penis or a vagina or whatever you got, having equal access to also being a good listener, having like being supportive, being soft, being restorative, like self-care, take a bubble bath, talk about your feelings, like you need to be both if you want to be whole. So, I would say, man or woman, I think having an access in any one direction, you could be so feminine that maybe you could use a little bit more solidity and a little bit more containment and a little bit more support. So, I think, really, just man or woman, it’s having a balance.

And if you’ve learned that it’s not okay to have emotions or be afraid or feel ashamed or feel uncomfortable, that’s all like weakness, and you just keep packing that down and moving forward, sometimes there’s a role in that. Sometimes you might be a Navy SEAL and you’re about to do some mission, and it’s like, okay, your feelings in this 42-minute period, I don’t really need your feelings right now. We have a task, your feelings might get us all killed. I need you to do the objective. We need to get this done.

And then, from there, saying, okay, now, we need to rest and digest and restore and be open and be able to purge and say, oh my God, during that 42-minute period, I was terrified and I thought I was going to die. And I thought you were going to die. And I wanted to cry. And being able to have a place to be able to actually fill up, purge, fill up, purge, masculine, feminine, like both of those are invaluable.

Dean Pohlman: Yeah, I like that idea. I like the fill up, purge. That’s a good way of describing it. But yeah, recognizing that there’s a time and place for both of those, but I think we get into the habit of if we never are vulnerable, then it gets hard to practice them, even in the situations that they are appropriate, or we don’t learn when those situations are appropriate.

Aaron Alexander: And sometimes, vulnerability can be kind of obnoxious. Like sometimes, it’s like the same thing. Like, we have such limited skills on a skill set around how to express ourselves in an organically vulnerable way that sometimes you see this on social media and such and a lot of like me, like new age bro world, one that brought so much just like the neutral, where it’s almost like nauseating the vulnerability. It’s like, oh.

Dean Pohlman: It’s too much.

Aaron Alexander: Yeah, like, bro, I get that you’re trying to get laid by that crystal spiritual chick, but it’s a little much, pull back, like chop some wood, dude.

Dean Pohlman: Yeah.

Aaron Alexander: And then the irony with that is then that crystal spiritual chick, she actually wants to hook up with the dude that chops some wood because ultimately, we’re all seeking polarity. So, if you’re a…

Dean Pohlman: I like seeing that in action. Finding like the super masculine guy and finding the super feminine. I have one friend like that in particular. It’s almost like, what do they talk about?

Aaron Alexander: That’s the bane of male-feminine modern dating dynamics. If you are, as Chris said on my podcast, boss babe clapping back or whatever, you likely won the term for this, of women wanting to date across or above socioeconomic status and men wanting to date across below, the term for that’s called hypergamy. It’s like a natural thing that happens in nature, humans across the board and women across the board, but at least happens in humans, a lot places in nature. Within that, if you are striving to be the boss babe and you have more education, higher socioeconomic status, you just got the fancy car, big place, big entrepreneur, don’t need no man, totally sovereign queen archetype gal, boss babe archetype gal, it might be not so easy. Suddenly, your pool of men that can fulfill that masculine role in your life becomes perhaps more limited based off of both of your guys’ value systems and stories of relationship.

And so, it can be kind of an interesting dynamic. And if you are that girl, ultimately, what you want is you want a strong masculine presence in your life because I think that’s inherent with most women, femininity. Probably, you have the tools to have a baby, like inherently, there’s probably some urge somewhere in there to procreate and make a child and make a nest and keep the child warm and fed and like, that’s so beautiful. But if you’ve been so effective at being the boss babe clapping back, suddenly, the only guys that would be fitting to polarize you because you’ve already occupied that kind of defender, I’ll take care of everything space so well, the only guys that would really fit would be kind of more like soft, feminine-type fellas because they’re like, well, me is this effeminate dude, I could really use some support and stability. And like, well, this girl, she’s that, and the girl is like, well, I could really use some support and stability. It’s like, well, you’ve already flexed that support and stability muscles so hard, it’s like hard to meet you.

Dean Pohlman: Yeah, I can definitely see that. I think that definitely, some women just naturally are inclined that way.

Aaron Alexander: Nothing wrong with it. It’s not right or wrong.

Dean Pohlman: Yeah. But I’d be lying if I did not say that I think that many women who probably aren’t better off suited leaning in that direction are doing it because this society is just, I don’t know how to describe it, but there is a social pressure to be less feminine.

Aaron Alexander: Oh, yeah. Yeah, yeah. And it’s going to swing back. I mean, depending upon what circles you’re on, and it’s swinging back right now. And that’s the way it goes. Democrat, Republican, masculine, feminine, they’re like, whoa, too much, new president. They’re like, whoa, too much, like more meditation and essential oils. That’s what we do. We’re just creatures trying to figure this thing out.

Dean Pohlman: Yeah. If only more of us recognize that we were just going to swing back and forth between these things and we– I don’t know, but then that wouldn’t be human, would it?

Aaron Alexander: No. And who’s to say?

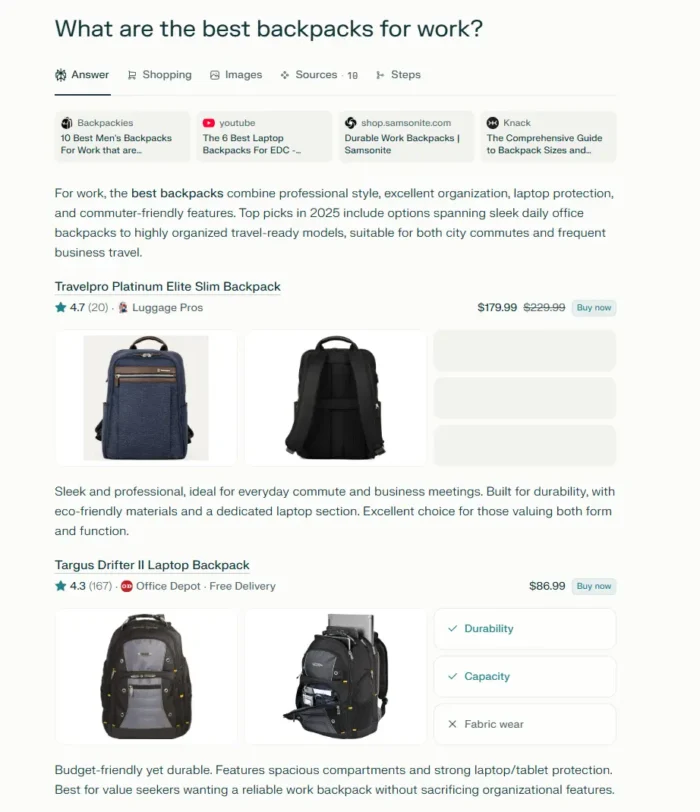

Dean Pohlman: I don’t know. So, alright. If you guys haven’t already, then go buy this book. It’s amazing. Aaron Alexander, The Align Method. This is the second edition of the book. So, what have you updated in the book, by the way?

Aaron Alexander: So, revised a ton of stuff throughout, just throughout the entirety of it, which is great to be able to come back a couple of years later and be like, oh, like, this could be better. So, there’s a ton of little micro additions and removals throughout this. I think it’s just a way cleaner read and way more like in my voice. When I first wrote it, there’s a little bit of, I think, pressure from the– just my own kind of stories of pressure, but from publishers and things that start to kind of like make it be for somebody else as opposed to just making it be like the most interesting expression that I would be interested in reading, essentially.

And then we added a whole chapter at the end that’s exclusively movement-based. So, taking people’s interests. It’s like a 45-minute or so movement sequence that gets through and gets into all the nooks and crannies of all your joints and connective tissues.

Dean Pohlman: Awesome. Yeah. And again, what I really like about it is, is that there’s just so much in here, but it really does seem like comprehensive. Like this seems like your– if you wanted to just have a conversation with Aaron, I feel like this does a fantastic job of doing that. Make sure you review it too. Those reviews are helpful.

Aaron Alexander: That’s true.

Dean Pohlman: So, how can people get more of you? What’s the best way to keep up with you, learn more about you, do some of your courses?

Aaron Alexander: So, yes, we have, if people want to go through– so, the book, to find the book, you just go to TheAlignBook.com, and that’ll take you to the page for it. It’s obviously on Amazon, all that stuff. The new version is the paperback version. That’s the revised expanded one. And then most people will probably just go to social media, so Instagram is @alignpodcast. I host a podcast called The Align Podcast. And as far as programs, you can find all that stuff through social media and the website and all that. But we do, if people are interested in going deeper into actually, have like video instructionals, like a curriculum, you can also find all that stuff at AlignPodcast.com.

Dean Pohlman: Perfect. Awesome. Alright. I think that’s it. Anything else you want to say?

Aaron Alexander: No. It’s really fun. Thanks for doing this, man. I appreciate getting to make this happen. I love that we’re recording remotely, even though we’re like 10 minutes from each other.

Dean Pohlman: I know, right?

Aaron Alexander: It’s actually worked out oddly well.

Dean Pohlman: Yeah, I know. I need to get the in-person thing setup.

Aaron Alexander: There’s something about proximity. It’s kind of interesting. I think just knowing that you’re like 10 minutes down the street, like it kind of almost feels like we’re in person.

Dean Pohlman: Yeah. If we needed to, we could very quickly be in person. And thank you for being one of my first guests. So, I really appreciate having you on here. Guys, again, Aaron Alexander, The Align Method Second Edition is out. Thank you so much for joining me on the Man Flow Yoga podcast, and have a great day. See you on the next piece of content I’m on. [END]

MikeTyes

MikeTyes