Alternatives to “Seated” Meditation: Dance, Stand, Drum, Chant, and Move Your Way to Active Enlightenment — Taking a Stand: Activity Yogas

In Buddhism, we tend to use the word “practice” for our meditation sessions. Contrary to the cliche of the seated vajra-posture, eyes half-closed in contemplation, most “practices” involve activities: prostration, sutra or mantra recitation (speech), walking, drumming, chanting, chiming,...

Fortunately, Buddha spent much of his time walking from teaching to teaching — not always seated in meditation. Here, a would-be killer tries to attack him on the road. No matter how fast the killer runs, Buddha’s walking keeps him out of reach. Ultimately, the killer gives up and becomes one of Buddha’s disciples. Aside from the symbolism, one of the things we learn from this teaching is walking and fitness are important practices to a sound mind.

Fortunately, Buddha spent much of his time walking from teaching to teaching — not always seated in meditation. Here, a would-be killer tries to attack him on the road. No matter how fast the killer runs, Buddha’s walking keeps him out of reach. Ultimately, the killer gives up and becomes one of Buddha’s disciples. Aside from the symbolism, one of the things we learn from this teaching is walking and fitness are important practices to a sound mind.In Buddhism, we tend to use the word “practice” for our meditation sessions. Contrary to the cliche of the seated vajra-posture, eyes half-closed in contemplation, most “practices” involve activities: prostration, sutra or mantra recitation (speech), walking, drumming, chanting, chiming, performing mudras — even dancing.

In Zen, these activities might include sutra recitation, fish drum, and gong, walking meditation, or a good “whack” with a stick by the teacher. In other forms of Mahayana Buddhism, the activities are even more diverse: Chod practice, martial arts, music, dance. In Vajrayana Buddhism there are countless activities: mandala offerings, thangka painting and sand mandalas, water bowl offerings, circumambulation of stupas, prayer wheel spinning, karma yoga (volunteer activities for charity, etc) and more.

Shaolin Kung Fu is actually a “yoga” or meditation practice, in Buddhism, not just a defensive art.

Shaolin Kung Fu is actually a “yoga” or meditation practice, in Buddhism, not just a defensive art.

This may come as a relief to those of us who suffer from issues such as arthritis, injuries or just, simply, aging.

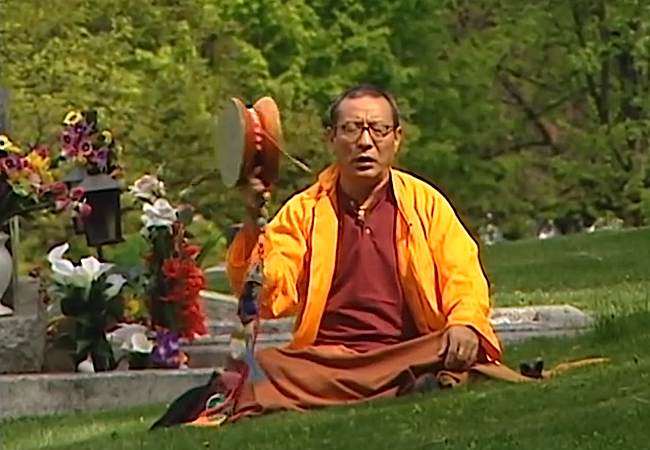

Chod practice is another very “active” form of meditation, albeit seated

Chod practice is another very “active” form of meditation, albeit seated

The Majority of Buddhist Practice Does Not Involve Sitting

The vast majority of Buddhist practice does not involve “seated” meditation, despite phrases such as “just sit” for Zen Buddhists, or “vajra posture” during Sadhanas in Vajrayana. Seated practice can be a “pain in the meditation cushion” for some people with disabling conditions. Although I’m quoting out of context, it can be helpful to remember the words of Buddhist teacher Anne Carolyn Klein[3]:

“Too often we stand in the way, and worry and obsess. It becomes a real interference with practice.”

Activity Yogas, such as Prostration and circumambulation — both shown in this image from the great stupa in Katmandu, Nepal — are ways that Buddhist practitioners can remain active while meditating and visualizing.

Activity Yogas, such as Prostration and circumambulation — both shown in this image from the great stupa in Katmandu, Nepal — are ways that Buddhist practitioners can remain active while meditating and visualizing.Typical activities include mudras, mantras, stupa or Holy Object circumambulation, prayer wheel spinning, walking meditation, prostrations, blessing objects, offerings — for example: pouring tea offering, water bowl offerings, mandalas. Many of the “foundation practices” for example, in Vajrayana Buddhism, involve activity yogas, such as mandala offerings, making tsa-tsas, prostrations, and mantra recitations.

Mandala offerings are very active forms of veneration and meditation. For a feature on Mandala offerings, see>>

Mandala offerings are very active forms of veneration and meditation. For a feature on Mandala offerings, see>>Movement and Buddhist Meditation

Although there are various meditation “modalities” such as “walking meditation” and “standing meditation” these are not necessarily core practices. For some people, such as myself, debilitating physical conditions such as arthritis, may necessitate alternatives to “just sitting.” Instead of full lotus, half lotus, quarter lotus, Seiza, Burmese or Vajra postures — various forms of somewhat uncomfortable seated postures — many ancient practices not only sanction motion, drumming, standing and dancing activities, they encourage them.

Mantra, for example, is active meditation with voice and breath, which can be performed while walking, standing, sitting, or any activity. Prostrations are active practices of devotion.

Prayer Wheel practice is a major daily “activity yoga” in Tibetan Buddhism. The wheel contains thousands of written mantras. The practitioner walks or stands or sits while rotating the wheel and visualizing the mantras going out to all sentient beings, blessing them. For a feature on Prayer Wheel Practice, see>> and here>>

Prayer Wheel practice is a major daily “activity yoga” in Tibetan Buddhism. The wheel contains thousands of written mantras. The practitioner walks or stands or sits while rotating the wheel and visualizing the mantras going out to all sentient beings, blessing them. For a feature on Prayer Wheel Practice, see>> and here>>

Many practices deliberately incorporate all of body-speech and mind, such as a combination of motion (walking or circumambulating), speech (for example reciting mantras or sutras) and mind in the form of visualization.

The meditator able to do all three at the same time is managing a complex meditative modality. In the Highest Yoga Tantra practices, notably the 11 Yogas of Naropa, even our daily activities are meditation. In this highly advanced practice, which typically requires a teacher, we are taught to view all sounds as mantras, all sentient beings as Buddhas, and all visual phenomenon as Pure Lands.

Spinning the giant prayer wheels, filled with hundreds of thousands of mantras each is a daily practice for many. Here, a devotee -meditator spins the wheels at Labrang Monastery, Tibet.

Spinning the giant prayer wheels, filled with hundreds of thousands of mantras each is a daily practice for many. Here, a devotee -meditator spins the wheels at Labrang Monastery, Tibet.

Activity — a More Complete Practice

Activity, standing, or dancing meditation, in other words, can be a superior method — not just a compromised alternative to sitting. If you can manage three activities of body-speech and mind together, you involve more concentration, which can be invaluable in our busy, modern lives. As Larry Mermelstein said, in a feature on modern-day Vajrayana:

“Our world is moving a lot faster than it probably was back in those days and so, yes, the stresses and complexities seem to be much greater than centuries ago. But so what? The very choicelessness of it is good for us. We have to do everything we can to incorporate the teachings on a continual basis in our lives.” [4]

Siddartha Buddha was an expert in martial arts. It developed mental discipline, focus and good health — all needed for meditation practices.

Siddartha Buddha was an expert in martial arts. It developed mental discipline, focus and good health — all needed for meditation practices.One of the methods we can incorporate the teachings into our lives is to adopt “no guilt” alternatives to traditional “sitting.” Walking has a long history in Buddhist practice, for example, circumambulating stupas while reciting mantras, but what about alternatives to formal seated methods — for example, during pujas and sadhana practices? Activities are already a part of these practices, albeit in restrained demonstrations such as prostrations, mudras, and mandala offerings. What if, however, a serious practitioner simply cannot “sit” during? What are the alternatives?

A monk meditates while walking at a monastery. In any environment, teachers often recommend walking meditation as an alternative to sitting meditation, especially to offset physical issues with long seated practice.

A monk meditates while walking at a monastery. In any environment, teachers often recommend walking meditation as an alternative to sitting meditation, especially to offset physical issues with long seated practice.No Guilt Alternatives to “Sitting”

There can be a sense of “guilt” or inferiority for someone who practices traditionally, but is unable to sit still due to infirmity or debility. There needn’t be. Here, I argue, with support of various practices, that “motion, dance, and stance” are equal to sitting practice — not compromises or inferior methods. Notable among these methods, are various meditative martial arts, exemplified in Shaolin Kung Fu or Zen Archery or Yogic exercises. In fact, motion and activity can enhance practice, even for people who could quite comfortably sit zazen all day.

Chanting and drumming are activity meditation methods in many schools of Zen. Here, Zen students chant with the famous “fish drum” or Mokugyo. This practice is about “drumming for a Wakeful Mind.” The Wooden Fish Drum’s unique sound is virtually iconic of Zen. For a feature on Fish Drums see>>

Chanting and drumming are activity meditation methods in many schools of Zen. Here, Zen students chant with the famous “fish drum” or Mokugyo. This practice is about “drumming for a Wakeful Mind.” The Wooden Fish Drum’s unique sound is virtually iconic of Zen. For a feature on Fish Drums see>>

Drumming, walking, standing…

Stillness of the mind (mindfulness) and or even visualization may seem to align naturally with “just sitting and breathing” but the opposite can be true for people where activities are the breakthrough method for overcoming conditioning. For example, active drumming is a powerful “mindfulness” meditation. Walking, listening, or even sports such as archery can be powerful “mindfulness” methods.

Chod practice by many monks. This active form of practice drumming is an advanced practice, combining activities with chanting mantras and visualizations.

Chod practice by many monks. This active form of practice drumming is an advanced practice, combining activities with chanting mantras and visualizations.

“You can meditate walking, standing, sitting or lying down,” said Buddhist monk Noah Yuttadhammo. “Each requires a different degree of effort as opposed to degree of concentration. Walking meditation having the highest degree of effort, lying meditation having the highest degree of concentration.” [2]

Related

For a feature on “Drumming for Mindfulness, see>> For a feature on “Dharma in Motion” and Martial Arts in Buddhism, see>> For a feature on Meditating with the Monkey Mind, see>> For a feature on Standing Meditation, see “The Better Way: Standing Meditation?”Zhang San Feng once said, “the chi goes where the mind goes” which was later paraphrased by body-builder Arnold Schwarzenegger, “Where the mind goes, the body follows” [1] This principle can be applied to our activities while meditating. Instead of simply visualizing without activities, we can help reinforce our visualization with a motion — especially for those of us who aren’t advanced Yogis or Yoginis.

Shaolin kung fu is almost synonymous with the Buddhist monastic discipline. For a feature on martial arts as a Buddhist practice, Dharma in Motion, see>>

Shaolin kung fu is almost synonymous with the Buddhist monastic discipline. For a feature on martial arts as a Buddhist practice, Dharma in Motion, see>>

There is an added benefit. One of the reasons the great Bodhidharma introduced martial arts into practice is to offset the damage to the health of monks and nuns who sit all day. However, in Shaolin practice, Kung Fu wasn’t just about making sure “monks stayed healthy and safe”; it was considered a core meditation practice and discipline.

Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh leads walking meditation at the Mahabodhi Temple in Bodhgaya India. For a feature on Thich Nhat Hanh, see>>

Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh leads walking meditation at the Mahabodhi Temple in Bodhgaya India. For a feature on Thich Nhat Hanh, see>>

Vajrayana: Standing, Dancing and Flying to Enlightenment

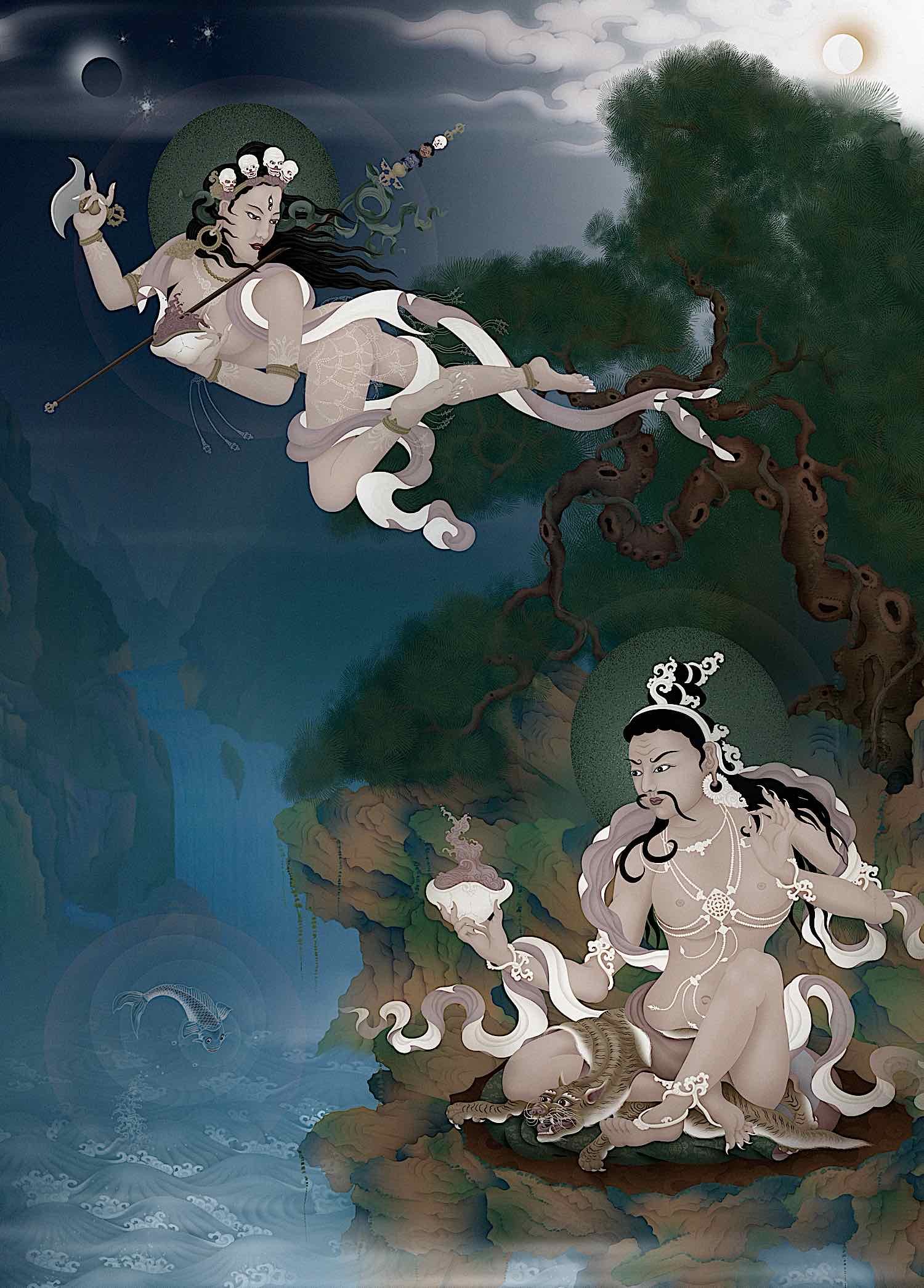

Especially in Vajrayana Buddhism, Enlightened aspects of Buddhas are often depicted dancing, standing, or riding in Thangkas. Most of the “Higher Yoga” aspects of Enlightened Beings are moving, not simply standing — which connotes activities. Nearly every Highest Yoga Tantra visualized Yidam is standing: Chakrasamvara, Vajrayogini, Yamantaka Vajrabhairva, Hevajra, Kalachakra, Ekajata, and so on. Activities become even more important when visualizing completion practices and yogas that prepare us for those practices.

In this Wangdu Thanka, the entire Padma (Amitabha) family — all aspects of Compassion — demonstrates different poses. Only some, notably Amitabha, Vajradharma and Avalokiteshvara are seated. Hayagriva (Amitabha’s fiercest emanation as a meditational aspect) Vajrayogini / Vajravarahi, Kurukulle, and the other “red” Yidam aspects are standing or dancing. Meditating on Compassion in its various forms is one of the powerful aspects of Vajrayana visualization.

In this Wangdu Thanka, the entire Padma (Amitabha) family — all aspects of Compassion — demonstrates different poses. Only some, notably Amitabha, Vajradharma and Avalokiteshvara are seated. Hayagriva (Amitabha’s fiercest emanation as a meditational aspect) Vajrayogini / Vajravarahi, Kurukulle, and the other “red” Yidam aspects are standing or dancing. Meditating on Compassion in its various forms is one of the powerful aspects of Vajrayana visualization.

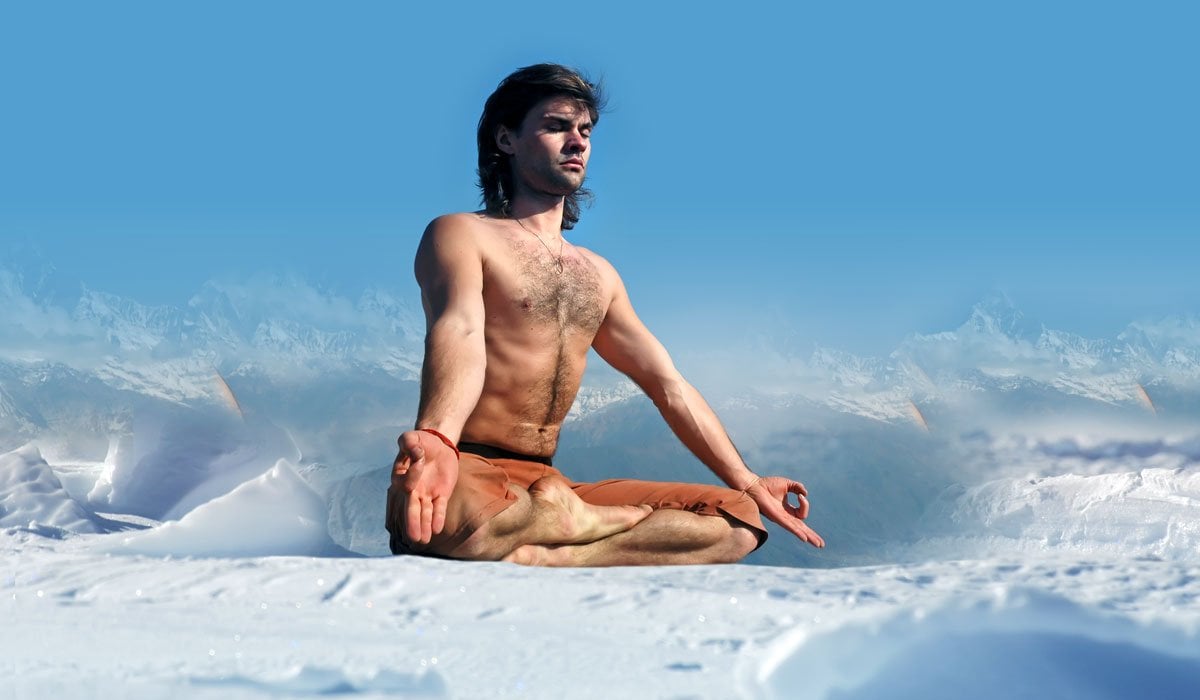

In Vajrayana Buddhist practices, even when we do sit, we are often instructed to visualize activities. In breathing meditation, we might visualize prana or chi interacting with our “inner bodies”. Body mandala practice is the ultimate “inner activity” visualization, which can manifest tangibly as generated body heat known as Tummo. [For a feature on Body Mandala practice, see>>]

Tummo “inner fire” meditation is a Vajrayana high practice. The control over the body is similar to that achieved by great masters of “chi” in kung fu. Although the practitioner here is seated, he is enabling inner activities in the inner body. The heat generated keeps him warm even in the sub-zero weather. (NOTE: Only under the guidance of a teacher!) For a feature on Tummo, see>>

Tummo “inner fire” meditation is a Vajrayana high practice. The control over the body is similar to that achieved by great masters of “chi” in kung fu. Although the practitioner here is seated, he is enabling inner activities in the inner body. The heat generated keeps him warm even in the sub-zero weather. (NOTE: Only under the guidance of a teacher!) For a feature on Tummo, see>>

In deity practice, which is an ultimately very empowering wisdom practice, we visualize ourselves in symbolic poses and appearances, and activities. As Vajrayogini or any of the Dakinis are inevitably depicted flying or dancing. Dakini can literally translate as “sky dancer.”

Stunning thangka detail of Tilopa visualizing a flying Dakini Enlightened deity. These great Mahasiddas and yogis reputedly could fly, walk through stone walls, and many other activities symbolic of Enlightened Mind. See more of Jampay Dorje’s stunning art at his website>>

Stunning thangka detail of Tilopa visualizing a flying Dakini Enlightened deity. These great Mahasiddas and yogis reputedly could fly, walk through stone walls, and many other activities symbolic of Enlightened Mind. See more of Jampay Dorje’s stunning art at his website>>The great biographies of the Enlightened Yogis more often describe them walking, flying, shooting arrows into rocks — often more akin to martial arts than classical “seated” practice.

Even during seated meditation, Vajrayana practices are filled with choreographed movements, such as mandala offerings, mudras, and other repetitive activities.

Venerable Zasep Tulku Rinpoche practicing Chod in a cemetery — from the movie “Come Again.” “The Chod practice dispels negative mental states, which are our “demons.” The Chod practice transforms mental defilement into the wisdom of Bodhichitta and Shunyata.” — from a description of an Chod initiation event and teaching from Zasep Tulku Rinpoche at Gaden Choling in Toronto. For a feature video Buddha Weekly documentary on Chod, see>>

Venerable Zasep Tulku Rinpoche practicing Chod in a cemetery — from the movie “Come Again.” “The Chod practice dispels negative mental states, which are our “demons.” The Chod practice transforms mental defilement into the wisdom of Bodhichitta and Shunyata.” — from a description of an Chod initiation event and teaching from Zasep Tulku Rinpoche at Gaden Choling in Toronto. For a feature video Buddha Weekly documentary on Chod, see>>

In Zen or Chan, drumming repetitively on the “fish drum.” In Zazen, our guide-instructor may occasionally whack us with a stick to “wake us up.” Of course, various yogas have always incorporated poses, positions and activities in practice. When working with the “energetic” body” many extraordinary activities can manifest, such as Tummo heat, where a naked yogi can actually comfortably meditate in the middle of winter. Even the “formless” meditations, such as Mahamudra and Dzogchen, still involve some ritualized activity.

A Buddhist monk performing formal walking meditation on a forest path. For a feature on “walking meditation” see>>

A Buddhist monk performing formal walking meditation on a forest path. For a feature on “walking meditation” see>>“You can meditate walking, standing, sitting or lying down,” said Buddhist monk Noah Yuttadhammo. “Each requires a different degree of effort as opposed to degree of concentration. Walking meditation having the highest degree of effort, lying meditation having the highest degree of concentration.” [5]

There is even a full Sutra, taught by Buddha, instructing on walking meditation. Full feature here>>

Practice for Arthritis: Standing or Moving

Recently, I re-arranged my little meditation area to allow for standing, posing and moving practice. I still have a chair, but rarely use it now, even for Highest Yoga Tantra Visualization Sadhanas. Fortunately, in my case, the practice I visualize is an Enlightened form who is always standing — actually dancing (Thangkas are misleading since they are a static moment in time) — so it feels natural for me to not just visualize myself standing and moving, but to actually “do it” while reciting the practices and visualizing the activities.

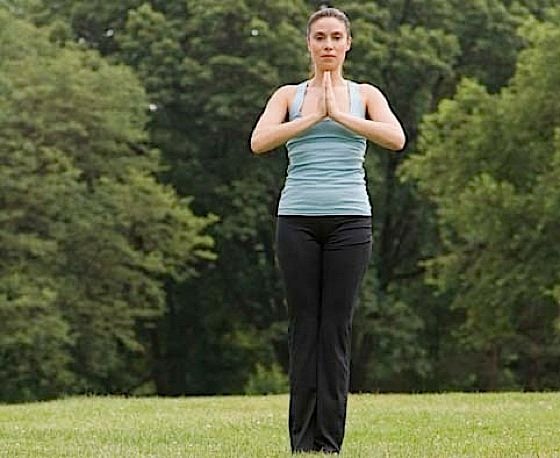

Standing meditation is a helpful technique for those who can’t “sit still”—people with the “monkey mind” or people suffering from painful conditions such as arthritis.

Standing meditation is a helpful technique for those who can’t “sit still”—people with the “monkey mind” or people suffering from painful conditions such as arthritis.I rarely, if ever, sit now. Although I began this practice due to pain and arthritis (particularly knees), I now find it enhances my practice. By adding the activates and motion I find it easier to visualize — in the same way as a hand mudra can symbolize an offering activity.

Zen Mindfulness can be achieved many ways, including concentrated activities such as skateboarding or martial arts. To see this feature on the Zen of Skateboarding, see>>

Zen Mindfulness can be achieved many ways, including concentrated activities such as skateboarding or martial arts. To see this feature on the Zen of Skateboarding, see>>

NOTES

[1] Body mandala practice in Vajrayana Tantric Buddhism — and riding the winds of the inner body “Where mind goes, the body follows” https://buddhaweekly.com/body-mandala-practice-in-vajrayana-tantric-buddhism-and-riding-the-winds-of-the-inner-body-where-mind-goes-the-body-follows/

[2] From feature on Standing Meditation: The Better Way: Standing Meditation? For those with injuries, arthritis or a sleepy mind, standing can help us achieve mindfulness

[3] In the quote, she was actually referring to visualization. Anne Klein

is founding director and resident teacher at Dawn Mountain Tibetan Temple, Community Center, and Research Institute in Houston, Texas. Quoted from:

“Forum: The Myths, Challenges, and Rewards of Tantra” in Lions Roar https://www.lionsroar.com/forum-the-myths-challenges-and-rewards-of-tantra/

[4] Larry Mermelstein, executive director of the Nalanda Translation Committee, and an acharya, or senior teacher, in Shambhala International, from “Forum: The Myths, Challenges, and Rewards of Tantra” in Lions Roar https://www.lionsroar.com/forum-the-myths-challenges-and-rewards-of-tantra/

[5] Standing meditation, the better way

Koichiko

Koichiko

![Language101 Review: I Wouldn`t Recommend At All [2021]!](https://www.dumblittleman.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Language101-Review.png)

.jpeg?trim=0,89,0,88&width=1200&height=800&crop=1200:800)