Appreciating Life and Creating a Life Worth Appreciating

Ann Tashi Slater talks with best-selling author Bianca Bosker about how art helps us live more expansively and brings us closer together. The post Appreciating Life and Creating a Life Worth Appreciating appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

Between-States: Conversations About Bardo and Life

In Tibetan Buddhism, “bardo” is a between-state. The passage from death to rebirth is a bardo, as well as the journey from birth to death. The conversations in “Between-States” explore bardo concepts like acceptance, interconnectedness, and impermanence in relation to children and parents, marriage and friendship, and work and creativity, illuminating the possibilities for discovering new ways of seeing and finding lasting happiness as we travel through life.

***

“In the everyday act of looking, our brains shape what we see,” says Bianca Bosker. “Art helps us break out of those well-worn pathways.” Bosker’s latest book, the New York Times best seller Get the Picture: A Mind-Bending Journey Among the Inspired Artists and Obsessive Art Fiends Who Taught Me How to See, explores what art is and how it can lead us to fresh perspectives.

Bosker’s research for the book took her deep into the New York art world, where she sold art in galleries, assisted artists in their studios, and worked as a security guard at the Guggenheim Museum. “I got drugged, dared, shamed, shushed, and befriended by art obsessives who treat paintings like vital organs and know how to find beauty where we least expect it,” Bosker writes. “In the process I discovered another existence, one where the act of looking is an adventure.”

Born in Portland, Oregon, Bosker is a contributing writer at the Atlantic. Her work appears in the New Yorker, the New York Times, the Guardian, and the Wall Street Journal, among others, and she’s the author of Cork Dork (2017), an insider’s look at the world of wine. “Both of my books grew out of a fear of death,” Bosker says. “Cork Dork is nominally about wine, but it’s also about our forgotten senses of taste and smell. Get the Picture is about art, but it’s also about learning to live life more expansively.”

From her home in Manhattan, Bosker talked with me about how changing our approach to art can “tweak our humanity,” freeing us to engage with ourselves and the world around us in a new way.

*

What was the inspiration for Get the Picture? One day, I was cleaning out my mother’s basement in Oregon and I found a watercolor my late grandmother had painted of dancing carrots. It was inspired by her time in a displaced-persons camp in Austria after World War II—she was a Jew in Warsaw when Hitler invaded Poland. At the camp, she used to tell me, she taught art to the children and organized a dance performance in which the kids dressed up as carrots. The moral of her story was that art is absolutely fundamental, even when the world as you know it has fallen apart.

Along with my grandmother’s painting, I found artwork that I’d done as a girl, when I dreamed of being an artist. Seeing it made me feel like I’d abandoned parts of myself by turning my back on art.

Even though you were having a lot of success as a writer. I’d had more success than I’d ever dreamed of with Cork Dork, and I felt good about my life. But at the same time, I realized I was doing work I loved with a mindset like Charlie Chaplin’s in Modern Times, always on the clock. Waiting for the elevator was an opportunity to respond to an email. In the toilet, I’d listen to a podcast on double speed while texting.

That day in my mother’s basement, I felt like I was missing out on something because I’d given up art for this hyperoptimized existence. That feeling, together with the reminder that art was what my grandmother turned to after she’d seen unimaginable horrors, motivated me to embark on the journey that became Get the Picture. The two questions I was looking to answer as I researched were, “Why does art matter?” and, “How do we engage with art more deeply?”

Some of the most important insights you had while working on the book are related to attention, which is a central concept in the Tibetan Book of the Dead. When we pay attention, the bardo teachings tell us, we can see the world with new eyes. What did you discover about attention? Paying attention to art helps us fight the reducing tendencies of our minds. We think we see like video cameras, objectively recording everything around us, but what’s actually happening is we have filters of expectation that dismiss, prioritize, and categorize all the raw data coming in, compressing our reality. Art helps us yank off the filters by introducing novel experiences and images that knock our brains off their axes and make our minds jump the curb.

One of the gallerists you worked with suggested that to really see a work of art, we should pay attention to context, an approach you describe as: “Look past the object till you catch sight of the idea, then gaze upon the identity of the artist.” An artist you interviewed proposed a different approach, telling you: “Just walk up to a piece and try to think of five things it brings up.” Which method have you found most effective for pulling off the filters? There’s a prominent mindset in the art world of basing your judgment of a work more in the context than in the object itself: who the artist is friends with, who the artist is sleeping with, where they went to school, who owns the work. Many art connoisseurs will tell you that without the context, you can’t understand what you’re looking at. When I encountered this, I felt like I was being encouraged to outsource my opinions to the hive mind, and that didn’t sit well with me.

I’ve found that the “think of five things” approach is a simple but helpful way to experience the full potency of a work of art. A lot of us feel like we have to have a PhD in art history or be a museum curator to have a meaningful experience with art. We spend more time reading the wall label than looking at the work itself because we think the label contains the “right” answer to how to understand the piece. The key is to learn to trust your own eye—to develop what artists call “visual literacy.” When you go to a museum or gallery, instead of trying to see everything, find one work that speaks to you and focus on what it brings up. Notice five things. Pay attention to the artist’s decisions.

If you’re willing to spend time with art, it will work its magic on you.

In bardo, we shape our experiences with our choices. Not just big choices but day-to-day choices that have far-reaching effects. Is spending focused time with a work of art an example of this? Yes, because it’s a choice you can make that can change how you see the world. I suggest that when you’re looking at art, you stay in the work itself, slowing down and noticing things about it. Studies show we spend an average of four to seventeen seconds with a work of art. Spend five minutes, fifteen minutes, maybe even fifty minutes. The things you notice don’t have to be grandiose, like, “This piece explores male-female relations in the post-internet age.” They can simply be observations: “This pink reminds me of a nipple,” or “That yellow is painted like a feather.” If you’re willing to spend time with art, it will work its magic on you.

Immersing myself in art in this way opened me up to discovering more beauty and depth in the world at large. I started doing this when I was researching Get the Picture, and I’d leave the gallery where I was working, or the Guggenheim, or a show, and feel the street scene of Manhattan completely transformed. Hot dog carts looked like sculptures; a tree twisting up from the sidewalk was a commentary on nature and the city.

What’s another way that a piece of art has changed your perspective? There are so many examples, but one was a work by a performance artist named Mandy allFIRE, who explores desire and the objectification of the female body. She issued an invitation to her hundreds of thousands of fans to come to a gallery to have their faces sat on until they “couldn’t take it anymore.” I went to the opening and allowed her—this nearly naked stranger—to sit on my face for about ten minutes. I was extremely skeptical of her work at the outset, but afterward I couldn’t stop thinking about it. AllFIRE’s work raises difficult questions, like: What is art? What is good art?

We go to a museum and look at a white canvas, let’s say by Rauschenberg, and think, I could do that. How come he got millions for it? Or we see Picasso’s bull’s head, which he made with a bicycle seat and handlebars, and we think, I can make that! I have an old bike seat and handlebars out in the garage. And anybody can sit on somebody’s face. How do we know if something is “art” and whether it’s worth spending time with? That was a huge question I had. I’d experienced going to a museum and seeing a bunch of people contemplating a sculpture of decaying vegetables on a stained mattress, and feeling like I was on Candid Camera.

I’ve come to think that art is a handshake between the creator and the viewer, where someone creates something, and then you, as a viewer, either pick it up as art or not. I’m willing to pick up allFIRE’s work as art. It has stuck with me more than countless, better-behaved pieces that I’ve seen at galleries. It has challenged my assumptions. It has made me uncomfortable. It has widened my perspective. These are all things that a great work of art can do. I’ve also discussed it with many different people, and everyone has an opinion. A piece that can get people debating what art is? That’s exciting.

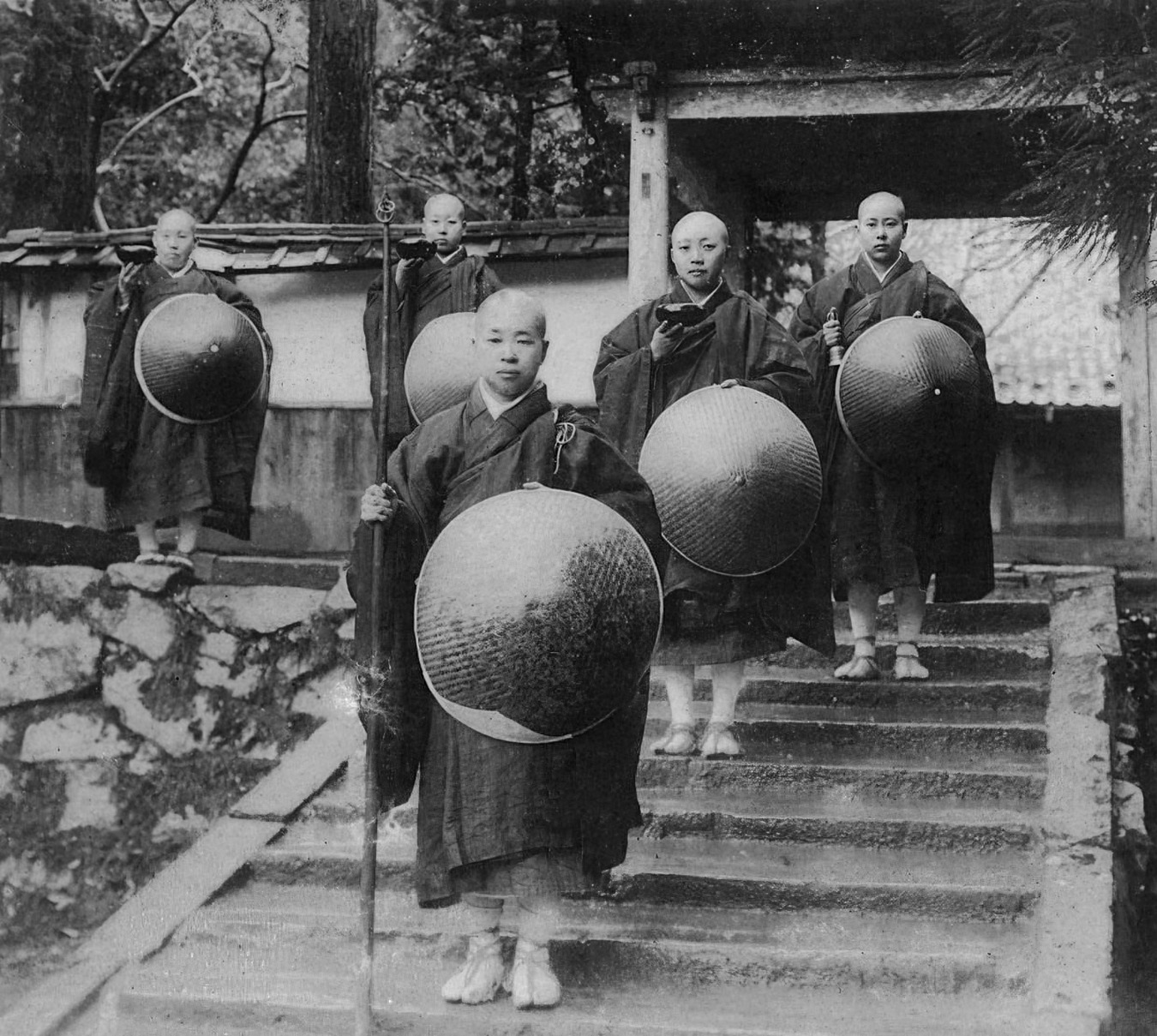

In Get the Picture, you say that—discussions about what is or isn’t art aside—art is a biological predisposition that increases our odds of not only surviving but thriving. How does it do this? Art is one of our oldest forms of expression and one of our most universal urges, not some pastime we came up with once we figured out how to live beyond 20 and ran out of things to do. There are various hypotheses for how it helps us survive and thrive as a species. One is that it binds communities together. With this definition, art could be a Super Bowl halftime show. It could be a tea ceremony. It could be a video game. The theory is that, whether it’s gathering around a fire in a cave to look at bison painted on the wall or going to a gallery to see a performance artist, art helps us make it in this world because it brings us closer together.

In your book, you say that art can also help us “fight against complacency,” which resonates with the idea in the bardo teachings that our time on the planet is limited and we should embrace life. How can art lead us to live more fully? There’s an artist, E’wao Kagoshima, whose work I was introduced to early on in my immersion in the art world, and I couldn’t understand why gallerists were so obsessed with it. I felt like it was an example of the arbitrariness and delusion of the art world. But I have not stopped thinking about his work, and when I finally finished Get the Picture, the first piece of art my husband and I purchased was by Kagoshima. It’s a painting of a woman holding a drink, nursing a fish on one breast, and this wild hairy dog, with a painted frame. I’m obsessed with it, and I just want to wake up to the moment of surprise and inspiration that it offers day after day.

Kagoshima’s painting reminds me that art is a choice. It’s a decision to live a life that’s more beautiful, more complex, and more nuanced. Ultimately, art is about appreciating life, but it’s also about creating a life worth appreciating.

AbJimroe

AbJimroe