Are Branched-Chain Amino Acids Good for Us?

I discuss why we may not want to exceed the recommended intake of protein. Diabetes isn’t just about the amount of body fat, but also […]

I discuss why we may not want to exceed the recommended intake of protein.

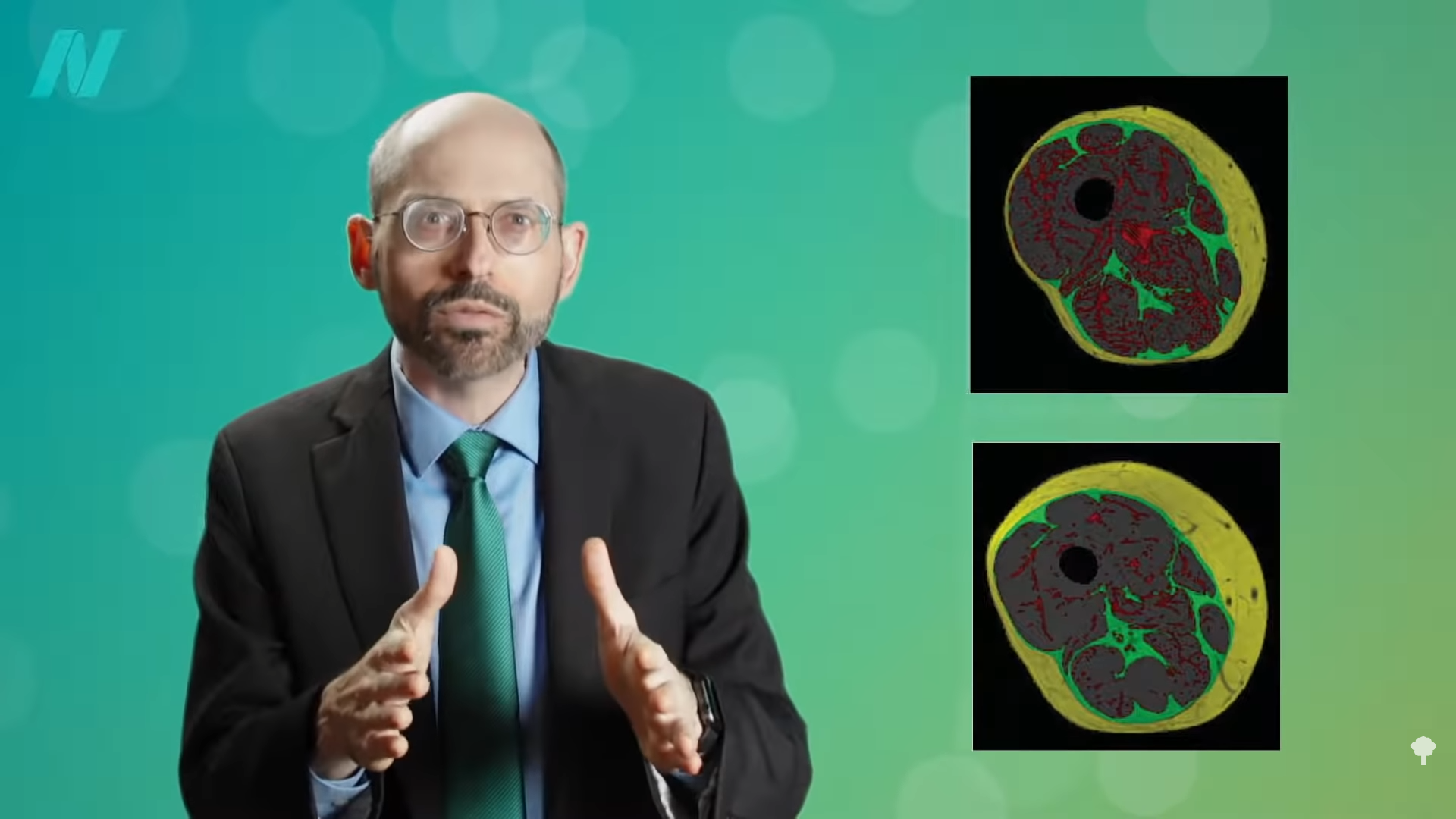

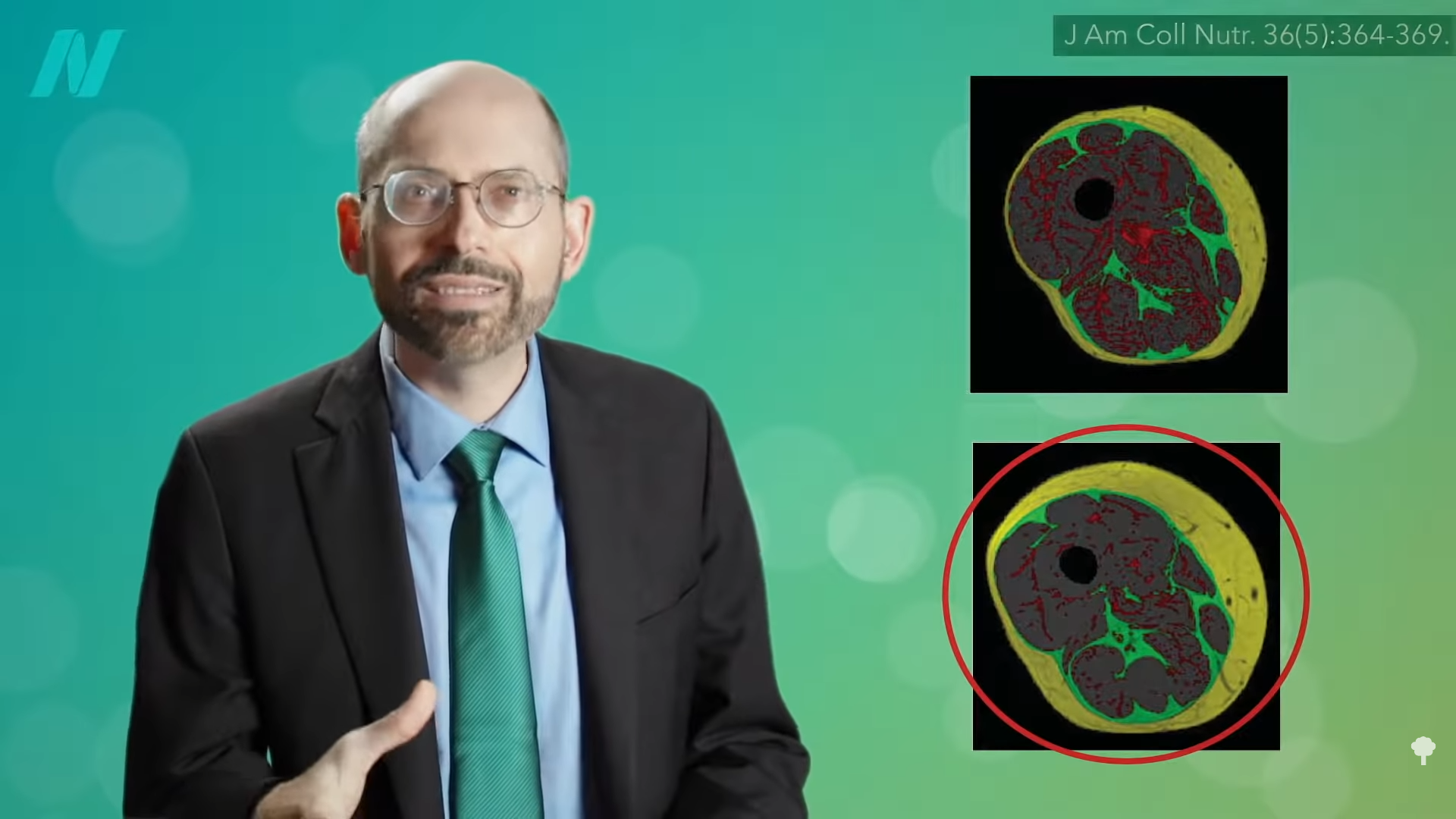

Diabetes isn’t just about the amount of body fat, but also the distribution of body fat. At 0:26 in my video Are BCAA (Branched-Chain Amino Acids) Healthy?, you can view cross-sections of thighs from two different patients using MRI. In the images, the fat shows up as white and the thigh muscle is black. At first glance, you might think the bottom cross-section has more fat since it’s ringed with more white. That is the subcutaneous fat, the fat under the skin. But, if you look at the top cross-section, you’ll see how the middle of the thigh muscle is more marbled with fat, like those really fatty Japanese beef steaks. That is the fat infiltrating into the muscle. In the graph below and at 0:48 in my video, the two cross sections are colored so you can see the different types of fat: the fat infiltrating the muscle in red, the fat between the muscles in green, and subcutaneous fat outside of the muscles and under the skin in yellow. If you add up all three types of fat, both of those thighs actually have the same amount of fat—just distributed differently.

This seems to be the critical factor in terms of determining insulin resistance, the cause of type 2 diabetes. Researchers found that the subcutaneous adipose tissue, the fat right under the skin, was not associated with insulin resistance. Going back to the two cross sections, as seen below and at 1:20 in my video, it is healthier to have the bottom thigh with the thicker ring of subcutaneous fat but less fat infiltrating muscle than the top thigh with more fat present in the muscle.

Is it possible a more plant-based diet also affects a more healthful distribution of fat?

We now know the effect of a vegetarian diet versus a conventional diabetic diet on thigh fat distribution in patients with type 2 diabetes. Researchers took 74 people with diabetes and randomly assigned them to follow either a vegetarian diet or a conventional diabetic diet. Both diets were calorie-restricted by the same number of calories. The vegetarian diet was also egg-free, and dairy was limited to a maximum of one serving of low-fat yogurt a day. What did the researchers find? The reduction in the more benign subcutaneous fat was comparable; it was about the same in both groups. However, the more dangerous fat—the fat lodged inside the muscle itself—“was reduced only in response to a vegetarian diet.” So, even getting the same number of calories, there can be a healthier weight loss on a more plant-based diet.

Those eating strictly plant-based also had lower levels of fat stuck inside the individual muscle fibers themselves, which may help explain why vegans in particular are often found to have the lowest odds of diabetes. It is not just because vegans are generally slimmer either. Even if you match subjects pound for pound, there is significantly less fat inside the muscle cells of vegans compared to omnivores. This is a good thing, since storing fat in muscle cells “may be one of the primary causes of insulin resistance,” which is what’s behind both prediabetes and type 2 diabetes. On the other hand, if you put someone on a high-fat diet, the fat in their muscle cells shoots up by 54 percent in just a single week.

What about a high-protein diet? That may undermine one of the principal benefits of weight loss: eliminating the weight-loss-induced improvement in insulin resistance. Researchers put obese individuals on a calorie-restricted diet of less than 1,400 calories a day until they lost 10 percent of their body weight. Half of the participants were getting more of a regular protein intake (73 grams a day), and the other half were on a higher-protein diet (about 105 daily grams). Normally, if you lose 10 percent of your body weight, your insulin resistance improves. That’s why it is so critical for obese individuals with type 2 diabetes to lose weight. However, the beneficial effect of a 10 percent weight loss was eliminated by the high protein intake. Those extra 32 grams of protein a day abolished the weight-loss benefit. “The failure to improve…insulin sensitivity in the WL-HP [weight-loss high-protein] group is clinically important because it reflects a failure to improve a major pathophysiological [cause-and-effect] mechanism involved in the development of T2D,” type 2 diabetes. In summary, the researchers concluded that they demonstrated “the protein content of a weight loss diet can have profound effects on metabolic function.”

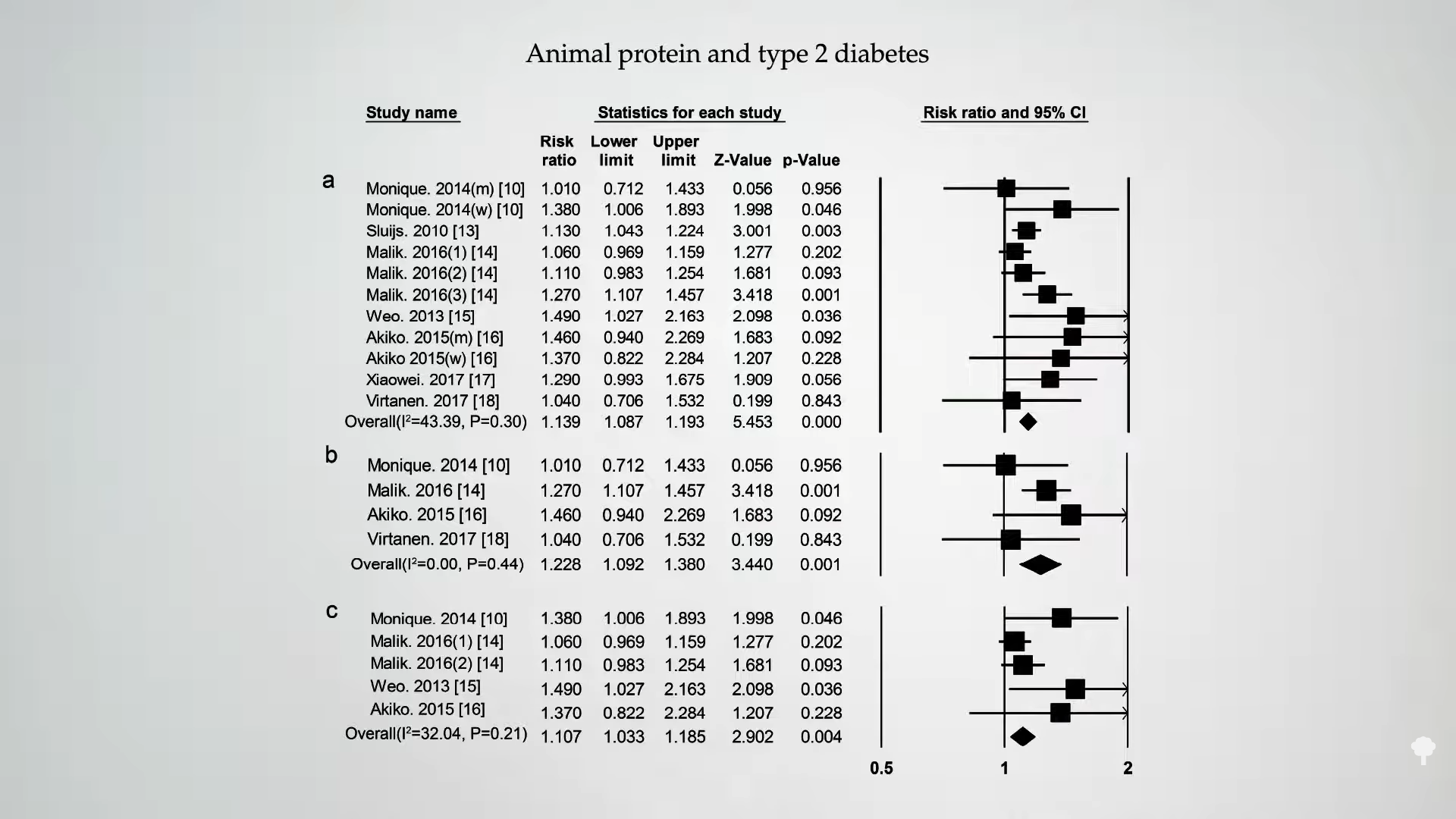

Is this true of any protein? As you can see below and at 4:19 in my video, if you split it between animal protein versus plant protein, following people over time, intake of animal protein is associated with an increased risk of diabetes in most studies.

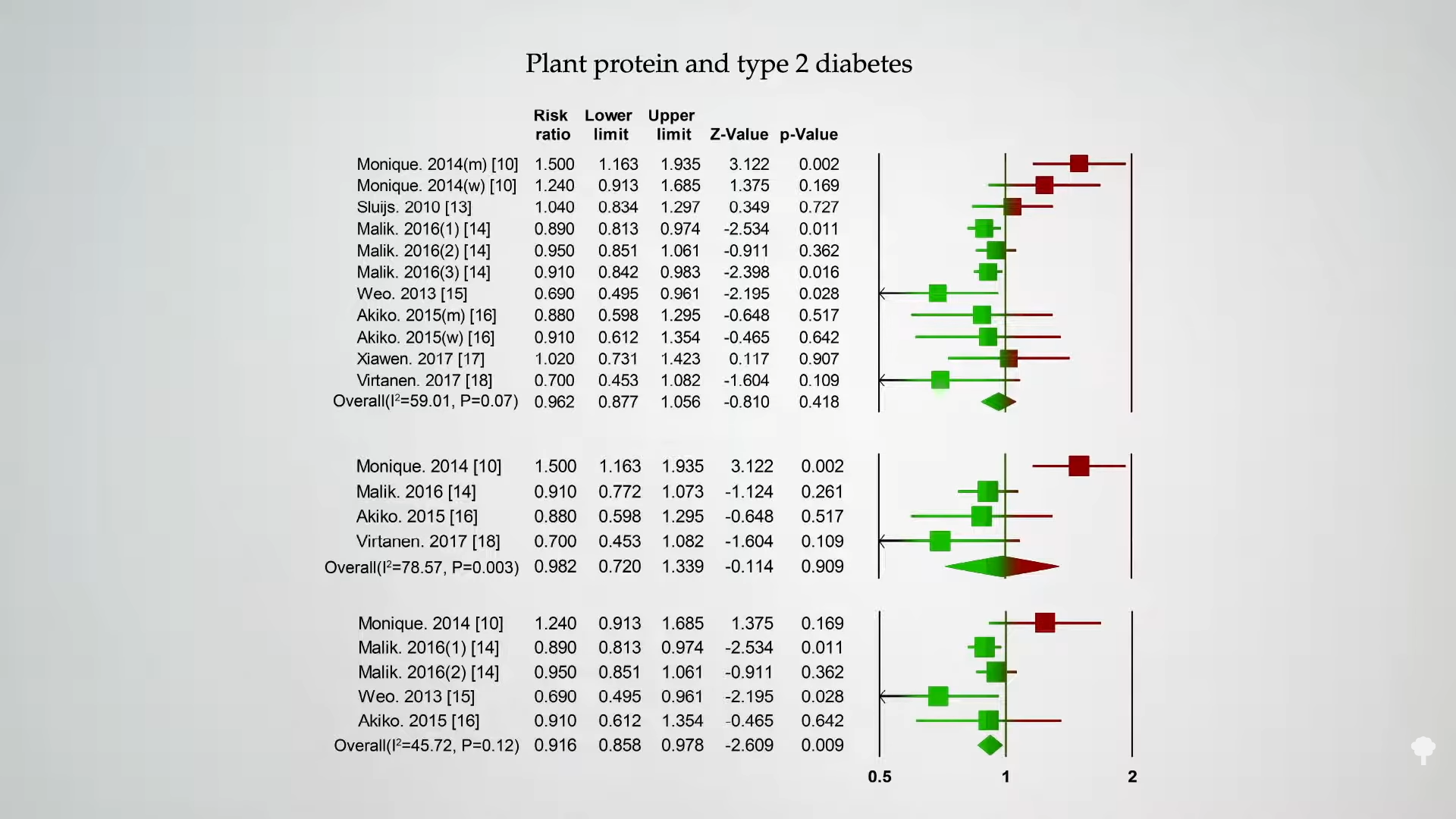

Intake of plant protein, however, appears to have either a neutral or even protective association with diabetes, as shown below and at 4:25 in my video.

Those were just observational studies, though. People who eat a lot of animal protein might have many unhealthy behaviors. However, you see the same thing in randomized, controlled, interventional trials, where you can improve blood sugar control just by replacing sources of animal protein with plant protein.

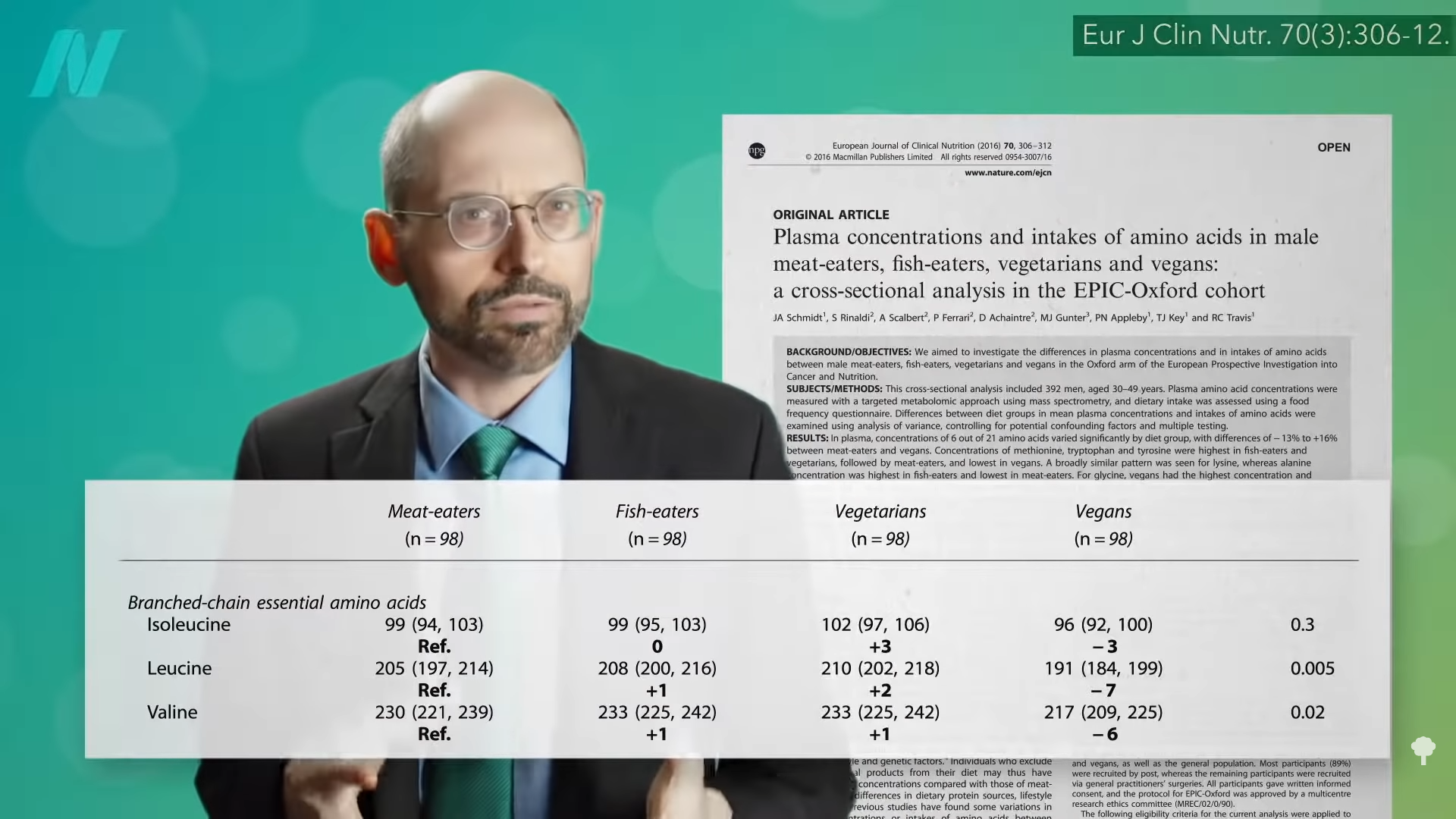

We think it may be the branched-chain amino acids concentrated in animal protein. Higher levels in the bloodstream are associated with obesity and the development of insulin resistance. As you can see below and at 5:00 in my video, we may be able to drop our levels by sticking to plant proteins, but you don’t know if that has metabolic effects until you put it to the test.

Ruining the suspense, researchers titled their study: “Decreased Consumption of Branched-Chain Amino Acids Improves Metabolic Health.” They demonstrated that “a moderate reduction in total dietary protein or selected amino acids can rapidly improve metabolic health,” and this included improving blood sugar control, while also decreasing body mass index (BMI) and body fat. As you can see at 5:27 in my video, the protein-restricted group was eating hundreds more calories per day, significantly more calories than the control group, so they should have gained weight. But, no. They lost weight! After about a month and a half, they were eating more calories but lost more weight—about five more pounds than participants in the control group who were eating fewer calories, as you can see at 5:38 in my video. What’s more, this “protein restriction” had people eat the recommended amount of protein per day, about 56 daily grams. They should have been called the normal protein group or the recommended protein group instead, and the group eating more typically American protein levels and suffering because of it should have been called the excess protein group. Just sticking to the recommended protein intake doubled the levels of a pro-longevity hormone called FGF21, too, but we’ll save that for another discussion.

To better understand the negative impact of omnivores getting too much protein relative to vegetarians, see my video Flashback Friday: Do Vegetarians Get Enough Protein?.

I have several additional videos and blogs that may help explain some of the benefits of plant-based proteins. Check in the related posts below.

Of course, the best way to treat type 2 diabetes is to get rid of it by treating the underlying cause, as described in my video How Not to Die from Diabetes.

Tekef

Tekef