Asian American & Buddhist

What are the challenges, joys, and practices of today’s Asian American Buddhists? And what does the future hold for Asian American dharma communities? Mihiri Tillakaratne, Renato Almanzor, sujatha baliga, Chenxing Han, and Rev. Marvin Harada engage with these and...

Mihiri Tillakaratne: What can Buddhism offer Asian American practitioners? Are there aspects of your sangha or community that you love and wish to see continue?

Renato Almanzor: At the East Bay Meditation Center in Oakland, California, a core pillar is radical inclusivity, which allows me to connect with various people of color, those with physical disabilities, and neurodivergent individuals. It’s beautiful to be together.

Another pillar is shared leadership: fostering a sense of belonging to and ownership of our sangha. There’s joy in living a spiritual practice that embraces who I am. When I falter, I practice my “oops” and “ouches,” learning to apologize, make amends, and inform people when they’ve harmed me. We are committed to repair, striving to be whole and accountable to our most divine selves.

sujatha baliga: The buddhadharma offers Asian Americans the same thing it offers everybody: the possibility of collective liberation. When I was growing up in rural Pennsylvania, my friends thought the buddhas and gods on my family’s altar were weird. Today, they’re proudly displayed throughout my house.

I’m focusing on embodiment—working on practices with body, speech, and mind—in ways that Western manifestations of Buddhism often don’t. While I was ashamed of my body and of our cultural practices as a child, today I love embodying my practice in my brown body, for example, while doing prostrations at the Gyuto Monastery.

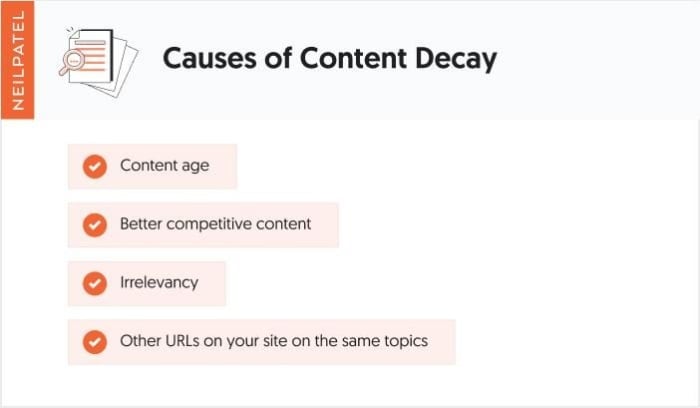

Calligrapher and peace activist Kazuaki Tanahashi once said, “If each stroke is our entire breath, how dare we correct it?”

Calligrapher and peace activist Kazuaki Tanahashi once said, “If each stroke is our entire breath, how dare we correct it?”“Miracles of Each Moment” by Kazuaki Tanahashi

Chenxing Han: For the past twenty years, I’ve been blessed to encounter the dharma through various communities, since frequent moves have prevented me from attending one temple regularly. I’m indebted to the Buddhist Churches of America (the BCA); numerous Cambodian, Vietnamese, Chinese, Taiwanese, Thai, and Lao temples; and places like the East Bay Meditation Center, for showing me the breadth and diversity of American Buddhism.

Asian Buddhist communities in the U.S. offer feelings of homecoming and refuge-making. They include intergenerational spaces, chants, rituals, liturgies, multiple languages, generosity, and ethics. Powerful women leaders, lay and monastic, are often the foundation of these temples and make these spaces feel like home. And the food! How could you not talk about the food?

Marvin Harada: Chenxing’s experiences offer valuable lessons. Sometimes, we stay within our tradition, but visiting other Buddhist traditions can broaden our perspective and understanding.

Mihiri Tillakaratne: What generational changes are seen in our communities? How can Asian American Buddhist communities foster multigenerational spaces?

Renato Almanzor: At East Bay Meditation Center, there’s a desire for both generational-

specific and multigenerational gatherings, including teen and family sanghas. These gatherings aim to cultivate and nurture our moral and ethical capabilities in a community with mutual accountability. Unlike the “do as I say, not as I do” approach of my parents, our sangha embraces, “Please tell me if I’m not living according with my aspirations.”

sujatha baliga: Most days, the monastery where I practice is a space for Tibetan Buddhists. On Sundays, it’s a diverse mix: mostly Asians of all flavors, some Tibetans, and the rest are Black, Latino, and white folks who’ve taken refuge or are interested in Buddhism.

The Tibetans bring children, who run around the grounds. The Asians are comfortable with it, knowing it’s a Tibetan Buddhist space. And we’re grateful we’re provided translation. Some folks who weren’t culturally used to children in these spaces initially gave the side-eye to the Tibetan families, but seeing our teacher’s loving, welcoming way with families pacified them. Each time that happened, it made me confident I’d done right by bringing my child to temple ever since he was born.

We also make structural accommodations for elders, like having chairs for those unable to sit on the floor. My mother sits on a chair up front while I lead meditation on Mondays, and our interaction in Konkani enriches the experience for others. Having my son and mother at temple offers a sense of longevity, showing these are lifetime practices.

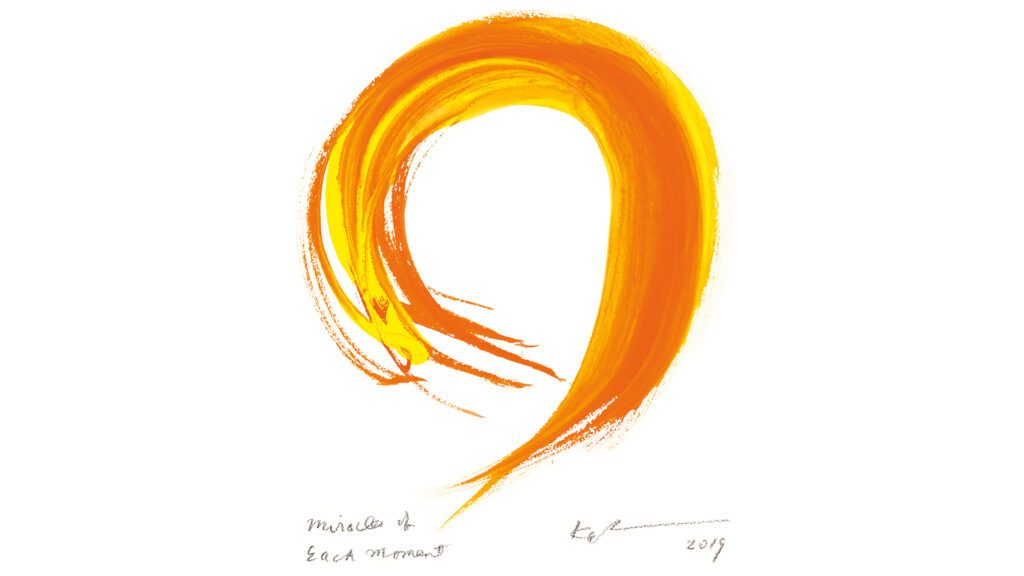

Wanxin Zhang’s sculptures are inspired by Chinese history, but he’s attempting to raise timeless questions. “Disciple #8” by Wanxin Zhang, courtesy of Catharine Clark Gallery, San Francisco

Wanxin Zhang’s sculptures are inspired by Chinese history, but he’s attempting to raise timeless questions. “Disciple #8” by Wanxin Zhang, courtesy of Catharine Clark Gallery, San FranciscoChenxing Han: So much of my thinking about generational change among Asian American Buddhists is shaped by Jodo Shinshu Buddhists who’ve been here for generations. Some of the same dynamics are happening with more recent immigrants.

There are language “barriers” or multilingualism, especially when younger generations are more comfortable with English. We see how this works over time: we still chant in Japanese at BCA temples, but dharma talks are usually in English now. Access is possible thanks to the extraordinary bridge people who have served as translators. Buddhism wouldn’t exist without 2,600 years of translation.

Generational changes outside Buddhist spaces happen within them, too, sometimes leading to tension. For instance, young people at home with gender fluidity may encounter traditions still organized by gender binaries. Political tensions, like those around Gaza and Israel, can cause generational strife. With today’s phones and social media, we might have to remind students to be present together.

I appreciate the question, “How can we foster more inclusive sanghas?” It’s easy to dwell on problems, but there are proactive steps we can take. Much of my joy comes from bridging lineages and traditions, learning from each other.

Marvin Harada: Shin Buddhism has always been cross-generational. Recently, many temples have aging sanghas and lack younger members. Some rural temples consist entirely of people in their seventies and eighties. The challenge is to reach younger people so we’ll have continuity.

I heard a minister say, “A sangha without the sound of a crying baby during the service is a temple without a future. Don’t think of that crying baby as an annoying sound, but as our future.” When I was a minister in Orange County, we created a cry room for parents with children to minimize service disruption. We encourage attendance from infancy. Older people learn from younger people’s enthusiasm and questioning.

Mihiri Tillakaratne: Besides generational issues, what challenges do our communities face, and how do we address them?

sujatha baliga: This is challenging for me to answer because I practice in a Tibetan cultural space but am of Indian descent, so I don’t want to speak for Tibetans. However, it’s important to acknowledge their struggles.

The Tibetan community is a refugee community facing the decimation of their culture and existence. Talking about it brings me to tears—the razed temples, stolen children, and forced boarding schools. What’s happening in Tibet always ranks amongst the top human rights violations on the planet. The growth of nunneries and the equal education of women in Tibetan Buddhism is a thrilling development, but the preservation of Tibetan culture itself is one of the greatest risks.

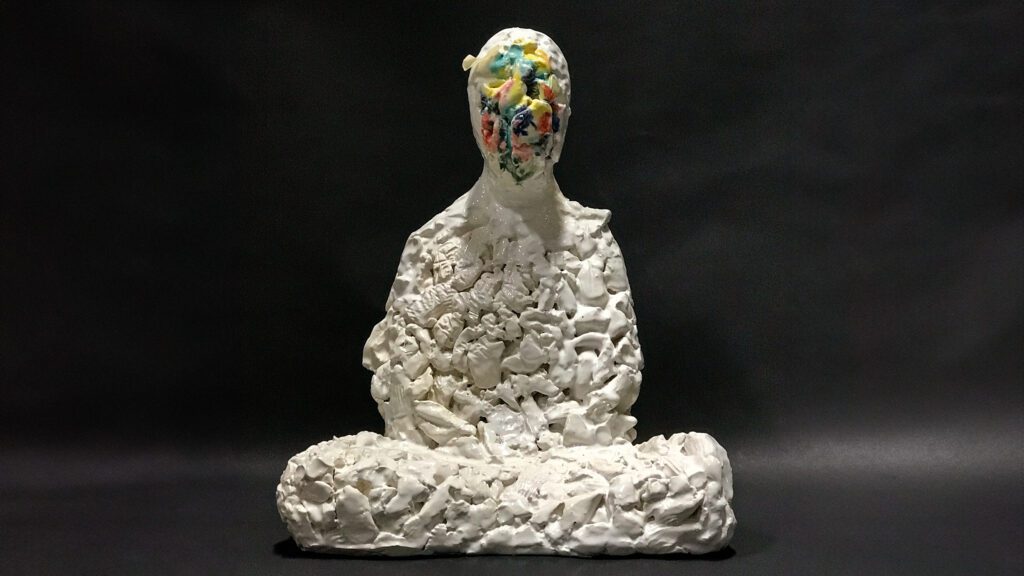

In her art, Miya Ando centers the natural world and expresses the Buddhist concepts of impermanence

In her art, Miya Ando centers the natural world and expresses the Buddhist concepts of impermanenceand interdependence. Photo of “Obon (The Returning of The Spirits),” installation by Miya Ando

Chenxing Han: As sujatha’s response illustrates, concerns in Asian American communities extend beyond America’s borders, involving transnational issues. Sri Lankan and Burmese Americans, for example, grapple with Buddhist nationalism in their home countries, similar to how others deal with Hindu nationalism. These conversations are difficult, but rising fundamentalism affects our Buddhist spaces, showing how interconnected everything is.

Structurally, much is missing. In hospitals, where chaplaincy training is most developed, for instance, the dominance of Christianity—the lack of Asian and Buddhist literacy—means many Asian-language-speaking patients die without receiving the Buddhist spiritual care they want or need.

There is also the challenge of discrimination and violence. Historically, the incarceration of Japanese Americans during WWII, as Duncan Williams’s work illustrates, was racially and religiously motivated. Today, Buddhism is still often erased, denigrated, or seen as a cult. Many majority-Asian Buddhist temples have experienced theft, sometimes in the form of violent robberies, reflecting the rise in anti-Asian violence. It’s frightening to think about these incidents, which put the lives and precious resources of fellow Buddhists at risk.

Marvin Harada: Some internal and external challenges can be seen as opportunities. For example, my friend became a Protestant minister, and in their tradition, the LGBTQ issue was really divisive. I said, “That’s not an issue with us!” LGBTQ people who aren’t accepted in other traditions can find a spiritual home in Buddhism.

How our predecessors handled great internal and external challenges is also important. Duncan Williams, in his book American Sutra, talks about how when Japanese Americans were put into internment camps, they wanted to celebrate the birth of the Buddha, but in an internment camp, nobody had a statue. So, someone carved a baby Buddha out of a carrot! We just make do, embracing challenges and moving forward with what we’ve learned from our predecessors.

Renato Almanzor: I’m not always sure it’s Buddhism that attracts people to our center. We have a sensibility—an engaged spirituality—that attracts folks committed to activism. I think often they find a place of refuge within EBMC, because it’s where they may be able to address their traumas. What’s challenging is we’re not necessarily equipped to deal with everyone’s processes.

Hurt people hurt people. So, we need to heal faster than the harm being done. Our center’s practice must be not just trauma-informed, but healing-centered. Our spiritual practices enable this, but our trauma responses of fight, flight, and freeze seem to still be habitual. We practice being with who and how we are, compassionately holding ourselves while experiencing trauma-related emotions without letting them dictate interactions with others.

We constantly discuss the three jewels (the Buddha, dharma, and sangha) and three poisons (greed, hatred, and delusion). Greed is facilitated by capitalism, hatred by oppression and racism, and delusion by dogma. None of us have escaped these forces. We must explore how—not if—we’re being racist or exclusive.

EBMC just bought a building in downtown Oakland, which has been gentrifying. We pride ourselves on diversity—ethnic, socioeconomic, gender, sexual orientation, and physical abilities—so collectively navigating the gentrification is tough. Being in sangha compels us to ask, “What does this mean, not just for me, but for you?”

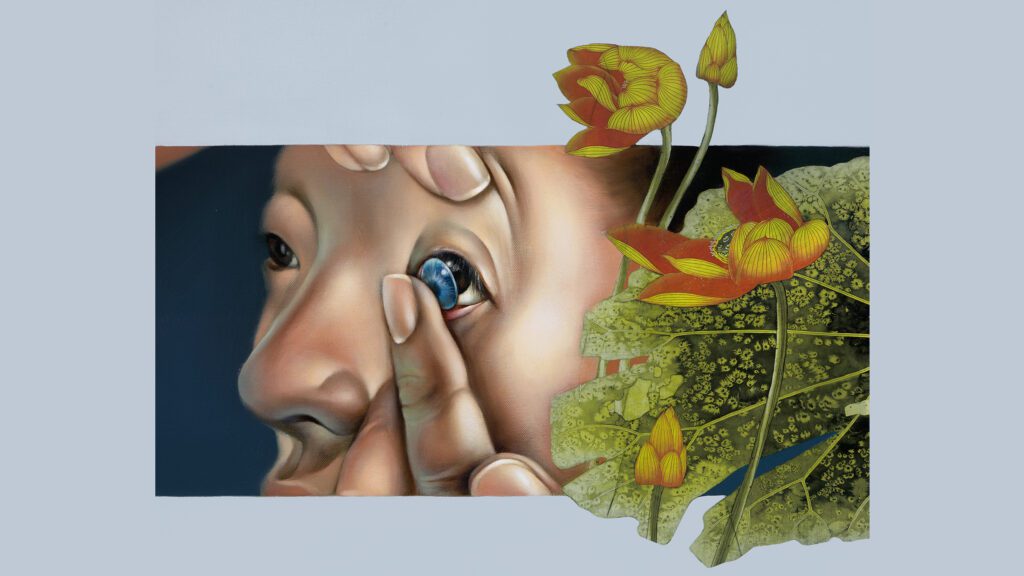

Buddhist artist Phung Huynh explores how Asian women are under pressure to conform to Western beauty standards. “Blue” by Phung Huynh

Buddhist artist Phung Huynh explores how Asian women are under pressure to conform to Western beauty standards. “Blue” by Phung HuynhMihiri Tillakaratne: What can Asian American “legacy” and “heritage” Buddhists learn from the experiences of Asian American convert Buddhists and vice versa?

Chenxing Han: I want to honor Aaron Lee, the “Angry Asian Buddhist” blogger who brought attention to the white-centric views of English-language Buddhist media. It’s hard to believe it’s been seven years since his passing. Many of us are indebted to his writing and legacy. I remember him grappling with heritage/convert distinctions, being Jewish through his mother and having a Buddhist grandmother.

These binaries are increasingly tricky, especially when talking to young people who may feel like a mix of heritage and convert, including second- and third-generation Black, White, Latinx, and Native Buddhists. There’s so much to learn from each other! In my work, I see the beauty in having a mix of people who feel more “culturally” Buddhist and those who are new to the practice.

Marvin Harada: As a minister at Orange County Buddhist Church for thirty-three years, I was fortunate to see legacy Buddhists welcoming newcomers, which greatly influenced whether they stayed. One elderly lady gave a young convert the collected works of Shinran—which cost fifty dollars—saying, “Here, you’ll need this someday.” He was so touched, and eventually he pursued the ministry.

Newcomers add much to our discussions, asking questions those raised in the tradition have never considered! Their curiosity and beginner’s mind remind us to maintain our own beginner’s mind.

Renato Almanzor: Being Asian American, there’s always a sense of not fitting in, of being part of something but not enough. My hair wouldn’t feather in the seventies, my nose looked a certain way, or my lips were too thick. With my dad in the Navy, we moved around a lot, and sometimes I was one of only four Filipinos—me and my three brothers. These feelings resurfaced when I started practicing Buddhism.

I met Chenxing at The Future of American Buddhism Conference at the Garrison Institute in 2022, and it was there that I wondered, “Am I Buddhist enough?” Despite my doubts, the curious and welcoming people at the conference contributed to my identity and development. There was camaraderie in honoring tradition without being bound by it. I was attracted to the practice, not obligated toward it.

sujatha baliga: For me, the challenge with the binary is that for some of us South Asians, especially South Indians and Nepalis, the line between Buddhism and Hinduism is blurry. There are three major differences that set Buddhism apart: one is that there’s no God, two is emptiness, and three is the bodhisattva vow. But everything else, like pujas and tantric practice, is essentially the same.

Yes, technically I’m a convert, but in the lineage I’ve landed in, I’ve never felt more at home culturally. It’s the closest thing in the United States to how I’d practiced in India.

The blessing for anyone teaching, formally or informally, is remembering why we do what we do. When someone unfamiliar with cultural aspects of spiritual practice asks questions, it reminds us of the reasons behind our practices. And those new to the practice can stop, listen, and learn why we do what we do, respecting cultural spaces without immediately thinking of making changes to make it more comfortable for themselves.

Mihiri Tillakaratne: What’s a concrete action Lion’s Roar readers can take to secure the future of their Buddhist communities?

Chenxing Han: Visit a local temple and observe what they’re doing. Bow, light incense, or make a donation—whether of money, time, food, or kindness. Stay for the meal and befriend someone. The most important part is to enjoy forming this karmic connection and spiritual friendship with others.

Marvin Harada: I’d say the same: Join a sangha. If any Lion’s Roar readers are “nightstand Buddhists” who’ve only read about Buddhism, I encourage them to experience sangha, either online or ideally in person. This helps the Buddhist centers, churches, or temples continue to transmit the dharma in this country.

Renato Almanzor: Examine how you are being inclusive or exclusive, and how your actions are healing or harming. Sometimes it’s about noticing what you’re already doing. Remember, you have options: choose to do something transformative and liberatory. It begins with knowing who and how you are now.

sujatha baliga: For those of us practicing within our own cultural traditions: Be proud! Love ourselves. Especially young people: don’t be ashamed of your heritage. Practice and explore Buddhism, and recognize the blessing of being connected to your cultural roots.

For Asians interested in other Asian traditions: help each other flourish. Visit temples and celebrate each tradition without being sectarian. Be excited about all the paths up the mountain, as they all lead to the top.

Welcome others without erasing ourselves. Sometimes we erase ourselves or water things down to make it palatable to other folks. Stand proud, make necessary adjustments for people of all races, but don’t abandon our identity in order to be accommodating. I don’t want to sift out the best of what we have to offer.

For non-Asians: For decades in the media, it’s been okay to mock Asians and our accents. “You love our food, but not us” kind of thing. Understand it’s a blessing to be invited into our spaces. Reflect on and remove the word “weird” from your language. Embrace the diversity and richness of our traditions, and recognize discomfort as a teaching moment rather than projecting it onto others.

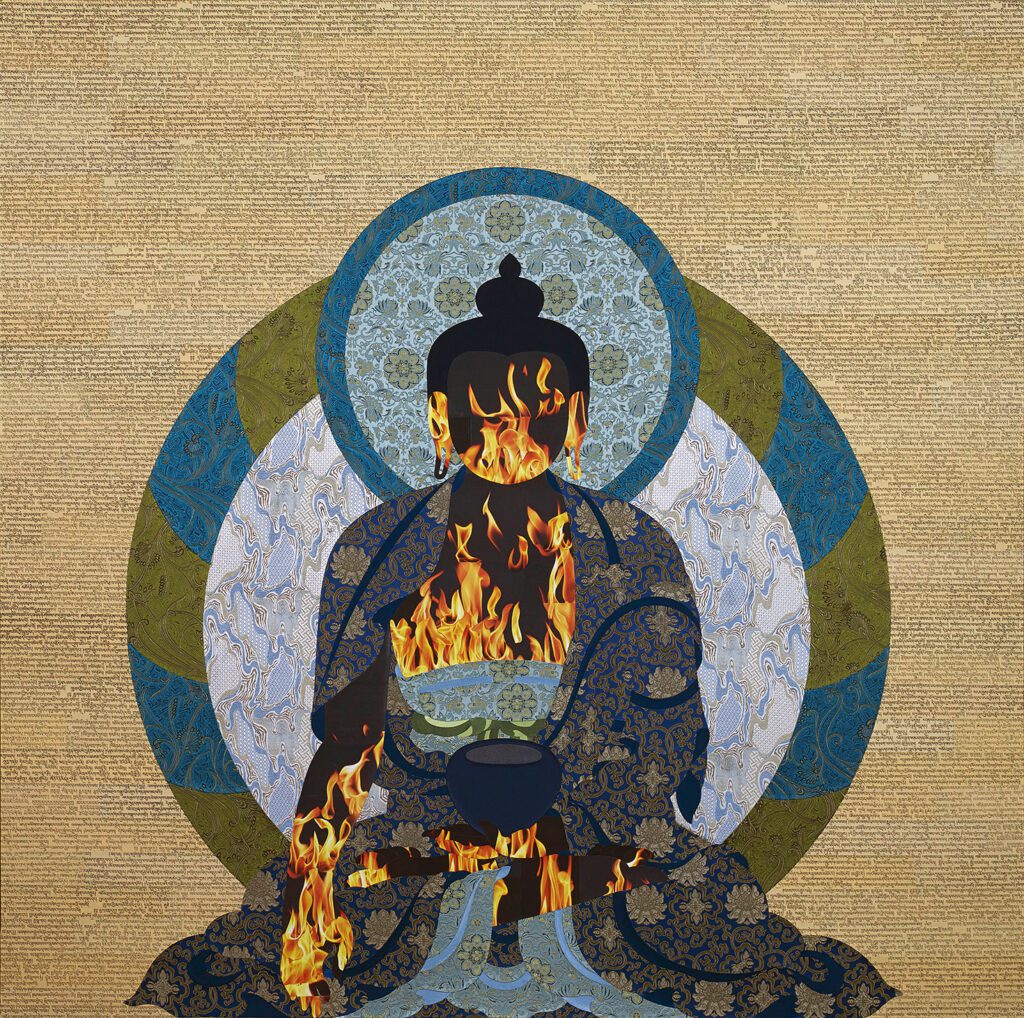

Self-immolation is used to protest the Chinese occupation of Tibet. “Both courageous and tragic, self-immolations challenge us, as witnesses, to either take action or to practice indifference,” says artist Tenzing Rigdol. Self-immolation is used to protest the Chinese occupation of Tibet. “Both courageous and tragic, self-immolations challenge us, as witnesses, to either take action or to practice indifference,” says artist Tenzing Rigdol.

Self-immolation is used to protest the Chinese occupation of Tibet. “Both courageous and tragic, self-immolations challenge us, as witnesses, to either take action or to practice indifference,” says artist Tenzing Rigdol. Self-immolation is used to protest the Chinese occupation of Tibet. “Both courageous and tragic, self-immolations challenge us, as witnesses, to either take action or to practice indifference,” says artist Tenzing Rigdol.Mihiri Tillakaratne: How do you envision the future of Asian American Buddhist communities?

Marvin Harada: I hope Buddhism reaches as many people as possible, including Asian American, African American, and Hispanic communities. I’d love to see our sanghas become more diverse. We’re not truly Buddhist if we think the dharma is only for certain communities. We’ll continue our tradition, but it must evolve to resonate with people of all backgrounds.

sujatha baliga: I’ve watched the buddhadharma flourish in the West in a way where it often loses the best of what it is. The best of our practices is beautifully entwined with our cultural traditions. Could we do it differently? Sure. But why not try the Asian way sometimes? These practices have been successful for 2,600 years! Maybe try our way for a minute?

Chenxing Han: The future of Asian American Buddhist communities is inseparable from the future of American Buddhism, which has often been reduced to white-convert Buddhism. The future of American Buddhism very much includes the future of Asian American Buddhism.

We should continue questioning: What does it mean to be American? To inhabit Turtle Island? To be immigrants here or once indigenous elsewhere? To be in a tradition that recognizes constant change and impermanence? To be Buddhist? What does enoughness look like?

There are as many ways to be Buddhist as there are Buddhists. Labels can either limit or expand possibilities. I hope we choose the expansive route, so that Asian American Buddhism becomes a home and refuge for everyone, even those who don’t identify as Asian American or Buddhist. When that happens, we’ll realize the liberatory potential of Asian American Buddhism.

Mihiri Tillakaratne (she/her) is an associate editor at Lion’s Roar. She has a PhD in Ethnic Studies and Gender, Women, and Sexuality (UC Berkeley), a M.A. in Ethnic Studies (UC Berkeley), and a M.A. in Asian American Studies (UCLA). She learned Pali and studied Sinhala Buddhist nationalism in post-independence Sri Lanka at Harvard. Mihiri is the director of I Take Refuge, a documentary on Sri Lankan American Buddhist identity, and the founder of Sri Lankan Americans for Social Justice.

Chenxing Han’s publications have appeared in Buddhadharma, Journal of Global Buddhism, Lion’s Roar, Pacific World, Tricycle, and elsewhere. Her first book, Be the Refuge: Raising the Voices of Asian American Buddhists, was published by North Atlantic Books in January 2021. www.chenxinghan.com

Rev. Marvin Harada serves as Bishop of the Buddhist Churches of America at the Jodo Shinshu Center in Berkeley.

Renato Almanzor, PhD, endeavors to be a transformation catalyst. He has over twenty-five years of experience developing leaders committed to equitable communities, multicultural organizations, and social justice.

As director of the Restorative Justice Project, sujatha baliga helped communities across the nation implement restorative justice alternatives to juvenile detention and zero-tolerance school discipline policies. She was a 2019 MacArthur Fellow.

JaneWalter

JaneWalter