Best of the Haiku Challenge (June 2025)

Announcing the winning poems from Tricycle’s monthly challenge The post Best of the Haiku Challenge (June 2025) appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

Announcing the winning poems from Tricycle’s monthly challenge

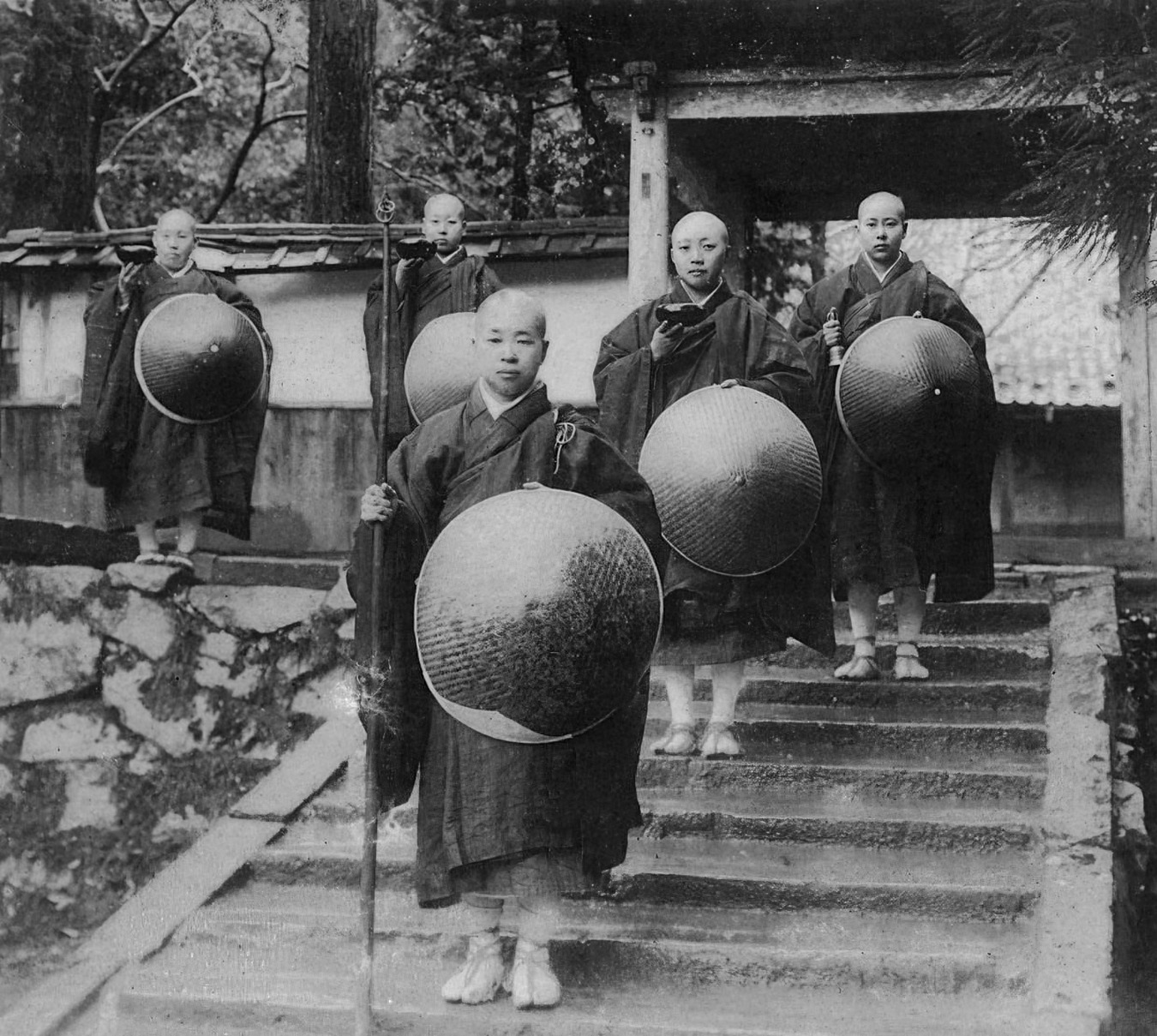

By Clark Strand Aug 01, 2025 Illustration by Jing Li

Illustration by Jing LiSummer lakes partake of the symbolism of water in general—one of the most complex and multifaceted symbols in all of literature. The association of summer lakes with leisure activity narrows the focus somewhat, but we may still find ourselves “in over our heads” in haiku on this theme. Each of the winning and honorable mention poems for last month’s challenge explored the unexpected depths of this otherwise mild, fair weather season word.

Marcia Burton’s poetic eye notices “the heads of swimmers” visible above the water, even as her heart registers their vulnerability. Kelly Shaw considers the possibility of spontaneous healing as he listens to the water lapping gently at the “summer lake’s edges.” Valerie Rosenfeld laughs “at how wrong it was” to feel burdened by life’s heaviness as she floats weightless at the top of the water.Congratulations to all! To read additional poems of merit from recent months, visit our Tricycle Haiku Challenge group on Facebook.

You can submit a haiku for the current challenge here.

Summer Season Word: Summer Lake

WINNER:

the heads of swimmers

the only things not swallowed

by the summer lake

— Marcia Burton

Why does a poem like last month’s winning haiku linger in the imagination after we read it? Why do we get the impression that it means so much more than it says?

The poem offers a literal, just-the-facts description of swimmers submerged in a summer lake so that only their heads are visible above the water. Were you to make that observation to someone standing beside you on the shore, they might assume you were thinking of painting the scene. On its surface, the image is of little more than visual interest to the eye. But one word changes everything.

On first reading, we might think, “Well, of course the swimmers’ heads aren’t swallowed by the summer lake—otherwise, they would drown.” Only after reading the poem for a second or third time does the word “swallowed” register as deliberately discordant with the relaxed, recreational tone of the poem.

Water is a life-giving natural resource, essential to the survival of plants and animals of every kind. But the symbolism of bodies of water is ambiguous at best. We can boat on a summer lake or ocean, or swim across its surface, but we are ultimately at its mercy. Its nature is to swallow things: people, ships, fortunes, occasionally entire cities. In the course of history, entire civilizations have vanished beneath the waves.

We suppress that knowledge when we embark on a journey by sea. And it goes without saying that we must put it out of our minds to enjoy a refreshing swim in a summer lake. But it can return in an instant. It only takes losing sight of one of those heads bobbing on the surface to bring back one of the oldest, deepest fears in the human repertoire.

That fear sits at the emotional center of this deceptively simple haiku, where it serves as a hidden counterweight to the joy that comes so easily in this season of relaxation and ease, as the waters that could swallow us lift our bodies and our spirits instead.

HONORABLE MENTIONS:

the lapping water

at the summer lake’s edges

am I being cured

— Kelly Shaw

all that heaviness

laughing at how wrong it was

in the summer lake

— Valerie Rosenfeld

◆

You can find more on June’s season word, as well as relevant haiku tips, in last month’s challenge below:

Summer season word: “Summer Lake”

promise me the moon

i say to the summer lake

the water says yes

We rented a house on a lake in Vermont. Knowing the moon would be full on the night we arrived, I walked to the end of the dock and waited. Finally, it rose above the mountains, casting its light on the still water. — Clark Strand

Submit as many haiku as you please on the season word “summer lake.” Your poems must be written in three lines of 5, 7, and 5 syllables, respectively, and should focus on a single moment of time happening now.

Be straightforward in your description and try to limit your subject matter. Haiku are nearly always better when they don’t have too many ideas or images. So make your focus the season word* and try to stay close to that.

*REMEMBER: To qualify for the challenge, your haiku must be written in 5-7-5 syllables and include the words “summer lake.”

Haiku Tip: Mix It Up!

Broadly speaking, there are two contradictory impulses at play in haiku poetry. The first is to preserve its basic elements: the 5-7-5 syllable form and the use of season words. The second is to mess things up a bit within those parameters.

You can’t have a short, accessible form that anyone can write in and expect the experts to have their way. Quite the opposite, in fact. Among the Honorable Mentions for last month’s challenge on “spring rain” was the following haiku by Scott Moore:

How to make spring rain:

Boil an ocean. Gather steam.

Misplace your jacket.

The poem is 5-7-5 syllables in form and has a season word, but in most other respects it flouts the conventions of haiku. And yet, Moore’s tongue-in-cheek parody of DIY culture is in keeping with one of the oldest teachings in the tradition.

The school established by Matsuo Bashō in the late 17th century revitalized haiku poetry by mixing “the high and the low,” combining the more elegant themes of classical linked verse with images and phrases drawn from ordinary life. Bashō was wary of burdening haiku with the kinds of rules that, while they might appeal to the literati, would narrow the range of its popular appeal.

The vast majority of haiku being written in English today (upwards of 90%, if not more) belong to the “Popular” genre—so called because they are written by non-specialists whose knowledge of haiku is limited to its 5-7-5 syllable form. That is the only rule for Popular Haiku, which means it’s all over the place in terms of content and style.

Moore’s poem is a bit of a hybrid. Its literary core (a portrait of the water cycle) is the stuff of Classical Haiku, while its comical phrasing (“Boil an ocean. Gather steam.”) is more typical of the Popular side of the genre. The purist might dismiss a verse like this as “definitely not a haiku.” In reality, it takes haiku back to its roots in comical literature as a form that mixes orthodox and unorthodox styles of writing.

A note on summer lake: Summer lakes are usually associated with recreation in haiku poetry—as a place to swim, boat, or fish during the warmer months of the year. But people also visit them to appreciate their natural beauty, or to relax in the cooler air along their shores. Lakes are more inviting in summer than at other times of year. In summer, lakes are also more likely to be tranquil or still.

![]()

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.

Astrong

Astrong