Best of the Haiku Challenge (September 2023)

Announcing the winning poems from Tricycle’s monthly challenge The post Best of the Haiku Challenge (September 2023) appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

Announcing the winning poems from Tricycle’s monthly challenge

By Clark Strand Oct 28, 2023 Illustration by Jing Li

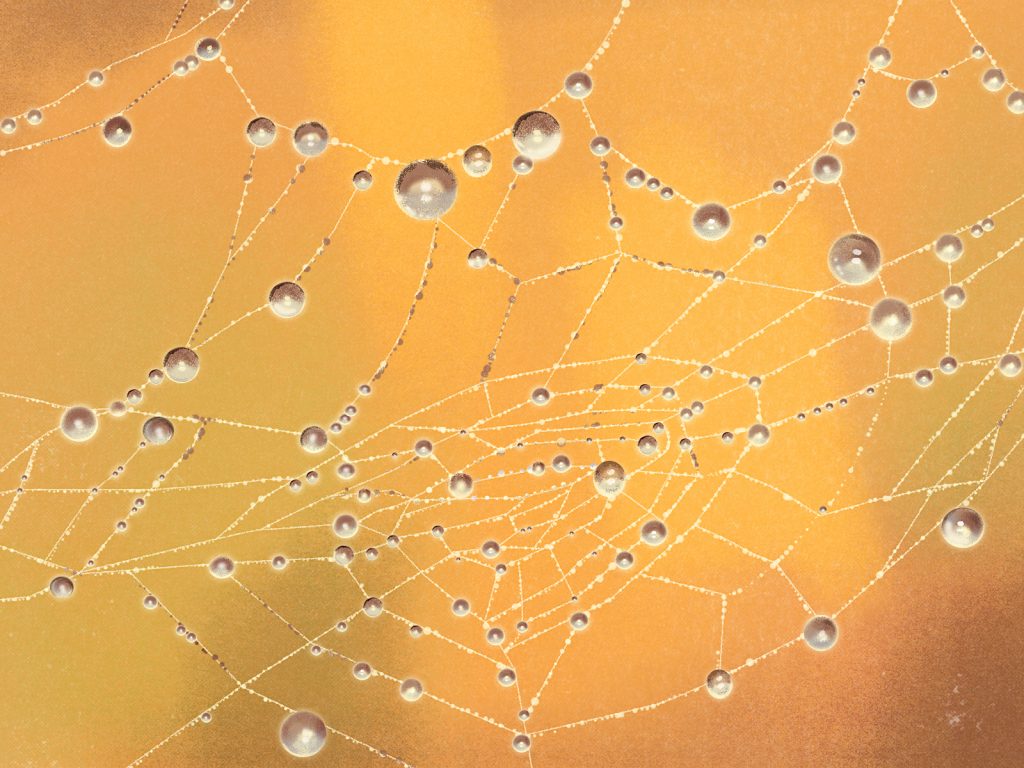

Illustration by Jing LiA season word is a repository for cultural memory as such memory relates to the changing seasons. Each word has a range of associations within that collective memory, but one of those associations is usually dominant. Because it vanishes by midmorning, the most common theme for “dew” is the passage of time. The winning and honorable mention poems for last month’s challenge each explored that theme—some with heartbreak, some with humor, and some with a mixture of both.

Valerie Rosenfeld addresses one of the oldest themes in poetry—the way life vanishes at death, seemingly without a trace. Gregory Tullock’s dew finds it expedient to practice nonattachment, given that it lives for “only one morning.”Nancy Winkler offers a satirical apology to leftover dewdrops for causing them to “miss the Rapture.”

Congratulations to all! To read additional poems of merit from recent months, visit our Tricycle Haiku Challenge group on Facebook.

You can submit a haiku for the October challenge here.

***

WINNER:

only morning dew

when I come to visit you

but no headstone yet

— Valerie Rosenfeld

In the five decades since I discovered haiku, I have returned to one lesson more often than any other: less is more. But “less” doesn’t mean fewer words or syllables. The point of haiku is not to strip language down to its bare essentials, but to use language to show how full one moment of life can be.

Our winning haiku for the September Tricycle Haiku Challenge employs a classical “hinge” in the final line. Only then does the door of the poem swing open to reveal the scene: a cemetery in the early morning, with the dew still wet on the grass.

A gravestone is more than a marker or a memorial. It serves as a portal between the world of the living and the world of the dead—the place we go to pay our respects, to offer flowers or prayers, or perhaps to converse with the dead. But what if the grave is so fresh that no stone has been set in place? Where is the portal then?

One of the oldest genres in Western poetry is a formal lament where each stanza begins with the words “Where are they now?” One can still find those Latin words, Ubi sunt, inscribed on gravestones in older cemeteries. For thousands of years poets have been asking, “Where are they now—the powerful, the beloved, the beautiful, or the wise?” But the question is always rhetorical. The answer is the grave.

Except when it’s not.

The brilliance of last month’s winning haiku lies in its simple, understated refutation of that age-old assumption. Where are they now? The answer is morning dew.

That image strikes a balance between beauty and heartbreak. Standing at the grave, the poet notices the small drops clinging to the grass blades surrounding the fresh dirt. There is no sign of the beloved’s presence apart from these. And yet, in their tiny bodies catching the morning light, is there not also something eternally present and made new?

On the one hand, there is “no headstone yet.” On the other, that stone, once set in place, will eventually wear away. The dewdrops are forever. Such thoughts are unavoidable for the haiku poet who celebrates the endless return of the seasons on their circular journey through time.

HONORABLE MENTIONS:

only one morning

the dew refuses to cling

to any future

— Gregory Tullock

an apology

to dew drops trapped in my shoes

missing the Rapture

— Nancy Winkler

♦

You can find more on September’s season word, as well as relevant haiku tips, in last month’s challenge below:

Fall season word: “Dew”

to a blade of grass

the dew has attached itself

using just water

Dewdrops were clinging to an upright grass blade. But, somehow, they didn’t slide down. I found it remarkable that the dew could form such a strong bond using only water.

Submit as many haiku as you wish that include the season word “dew.” Your poems must be written in three lines of 5, 7, and 5 syllables, respectively, and should focus on a single moment of time happening now.

Be straightforward in your description and try to limit your subject matter. Haiku are nearly always better when they don’t have too many ideas or images. So make your focus the season word* and try to stay close to that.

* REMEMBER: To qualify for the challenge, your haiku must be written in 5-7-5 syllables and include the word “dew.”

Haiku Tip: Raise the Bar for Zen Poetry!

Dewdrops have a long history in Japanese literature—especially in haiku poetry. Basho smiled at the sight of a mushroom covered in dew, still young and in its prime; Buson found dewdrops glistening at the tip of each bramble thorn; and Issa mourned the death of his infant daughter with a haiku that nearly every Japanese person now knows by heart:

the things of this world

are like dewdrops…yes, like dew—

and yet…and yet…

The most celebrated modern dewdrop haiku was written by Kawabata Bosha (1897–1941).

like a diamond

drop of dew sitting alone

on top of a stone

A Zen Buddhist monk who devoted himself to the intense observation of nature, according to the translator Makoto Ueda, “Bosha never tired of watching cats, butterflies, spiders and dewdrops; and, as he watched them closely, he sensed the workings of a superhuman will that made them behave as they did.”

In selecting material for his 2018 anthology Well-Versed: Exploring Modern Japanese Haiku, Ozawa Minoru chose Bosha’s dewdrop haiku as his most representative poem. He writes:

Dew of course is made of water, but here it is perceived as being as hard as a diamond, as the Zen priest Dogen (1200–1253) said of the Buddha dharma: “Frozen, it becomes harder than diamonds, who could break it?”

Ozawa cites a modern critic who suggested that Bosha had absorbed Dogen’s way of thinking, only to step beyond it. Anyone can see that ice is hard. To understand the indestructibility of a dewdrop requires a more ecologically-grounded perspective on the world. Perhaps Bosha was thinking of Basho’s advice to his own disciples: “Do not seek after the sages of the past. Seek what they sought.”

A note on dew: In his book Haiku World, William J. Higginson writes, “Autumn dew presages winter frost, and [signifies] the fleetingness of this life since it is usually gone by midmorning.” Season word editor Becka Chester offers a more naturalistic description of the theme: “Dew is like rain because both are formed by condensing water. As vapor cools in autumn’s night air, it slows down and its molecules collect across cool objects, such as foliage. In the morning, after a cool autumn night, we often find dew sprinkled lightly across grass, tree leaves, and other objects outdoors. If we’re lucky, we can find it suspended like tiny pearls in a spider’s web.”

![]()

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.

This article is only for Subscribers!

Subscribe now to read this article and get immediate access to everything else.

Already a subscriber? Log in.

BigThink

BigThink