Bond yields to climb 'for the wrong reasons' next year — and it will affect stocks, strategist says

"Something is interesting in the bond market ... and I think we have to be wary of it next year," said Peter Toogood, chief investment officer at Embark Group.

LONDON — Government bond yields are likely to rise in 2023 "for the wrong reasons," according to Peter Toogood, chief investment officer at Embark Group, as central banks step up efforts to reduce their balance sheets.

Central banks around the world have shifted over the past year from quantitative easing — which sees them buy bonds to drive up prices and keep yields low, in theory reducing borrowing costs and supporting spending in the economy — to quantitative tightening, including the sale of assets to have the opposite effect and, most importantly, rein in inflation. Bond yields move inversely to prices.

Much of the movement in both stock and bond markets over recent months has centered around investors' hopes, or lack thereof, for a so-called "pivot" from the U.S. Federal Reserve and other central banks away from aggressive monetary policy tightening and interest rate hikes.

Markets have enjoyed brief rallies over the past few weeks on data indicating that inflation may have peaked across many major economies.

"The inflation data is great, my main concern next year remains the same. I still think bond yields will shift higher for the wrong reasons ... I still think September this year was a nice warning about what can come if governments carry on spending," Toogood told CNBC's "Squawk Box Europe" on Thursday.

September saw U.S. Treasury yields spike, with the 10-year yield at one point crossing 4% as investors attempted to predict the Fed's next moves. Meanwhile, U.K. government bond yields jumped so aggressively that the Bank of England was forced to intervene to ensure the country's financial stability and prevent a widespread collapse of British final salary pension funds.

Toogood suggested that the transition from quantitative easing to quantitative tightening (or QE to QT) in 2023 will push bond yields higher because governments will be issuing debt that central banks are no longer buying.

He said the ECB had bought "every single European sovereign bond for the last six years" and, "suddenly next year ... they're not doing that anymore."

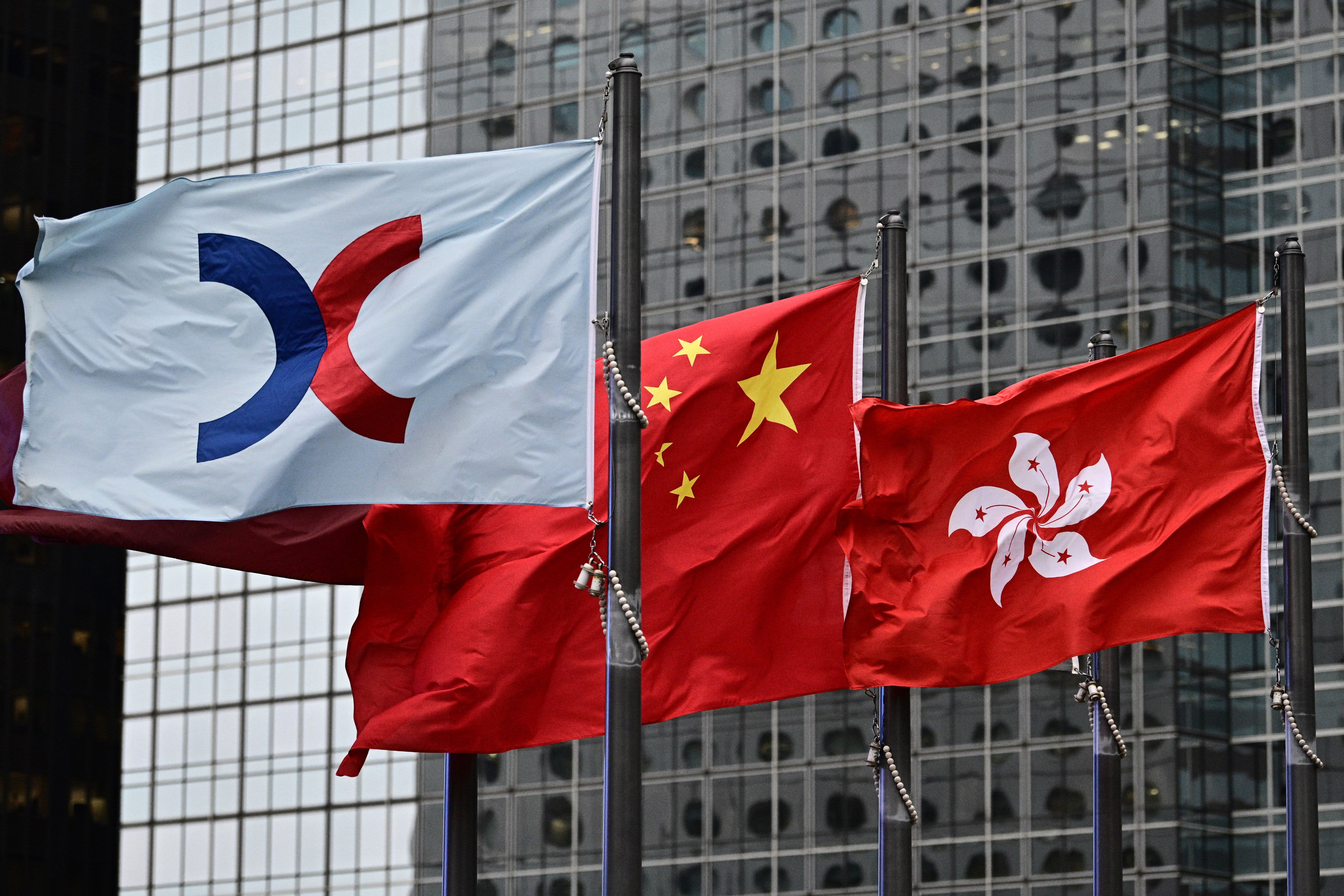

John Zich | Bloomberg | Getty Images

The European Central Bank has vowed to begin offloading its 5 trillion euros ($5.3 trillion) of bond holdings from March next year. The Bank of England, meanwhile, has upped the pace of its asset sales and said it will sell £9.75 billion of gilts in the first quarter of 2023.

But governments will continue issuing sovereign bonds. "All of this is going to be shifted into a market where the central banks are notionally not buying it anymore," he added.

Toogood said this change in issuance dynamics will be just as important to investors as a Fed "pivot" next year.

Stock picks and investing trends from CNBC Pro:

"You notice bond yields, are they collapsing when the market falls 2-3%? No, they are not, so something is interesting in the bond market and the equity market and they are correlating, and I think that was the theme of this year and I think we have to be wary of it next year."

He added that the persistence of higher borrowing costs will continue to correlate with the equity market by punishing "non-profitable growth stocks," and driving rotations toward value sectors of the market.

Some strategists have suggested that with financial conditions reaching peak tightness, the amount of liquidity in financial markets should improve next year, which could benefit bonds.

However, Toogood suggested that most investors and institutions operating in the sovereign bond market have already made their move and re-entered, leaving little upside for prices next year.

He said that after holding 40 meetings with bond managers last month: "Everyone joined the party in September, October."

UsenB

UsenB