Eating to Help Control Cancer Metastasis

Randomized controlled trials show that lowering saturated fat intake can lead to improved breast cancer survival. The leading cause of cancer-related death is metastasis. Cancer […]

Randomized controlled trials show that lowering saturated fat intake can lead to improved breast cancer survival.

The leading cause of cancer-related death is metastasis. Cancer kills because cancer spreads. The five-year survival rate for women with localized breast cancer is nearly 99 percent, for example, but that falls to only 27 percent in women with metastasized cancer. Yet, “our ability to effectively treat metastatic disease has not changed significantly in the past few decades…” The desperation is evident when there are such papers as “Targeting Metastasis with Snake Toxins: Molecular Mechanisms.”

We have built-in defenses, natural killer cells that roam the body, killing off budding tumors. But, as I’ve discussed, there’s a fat receptor called CD36 that appears to be essential for cancer cells to spread, and these cancer cells respond to dietary fat intake, but not all fat.

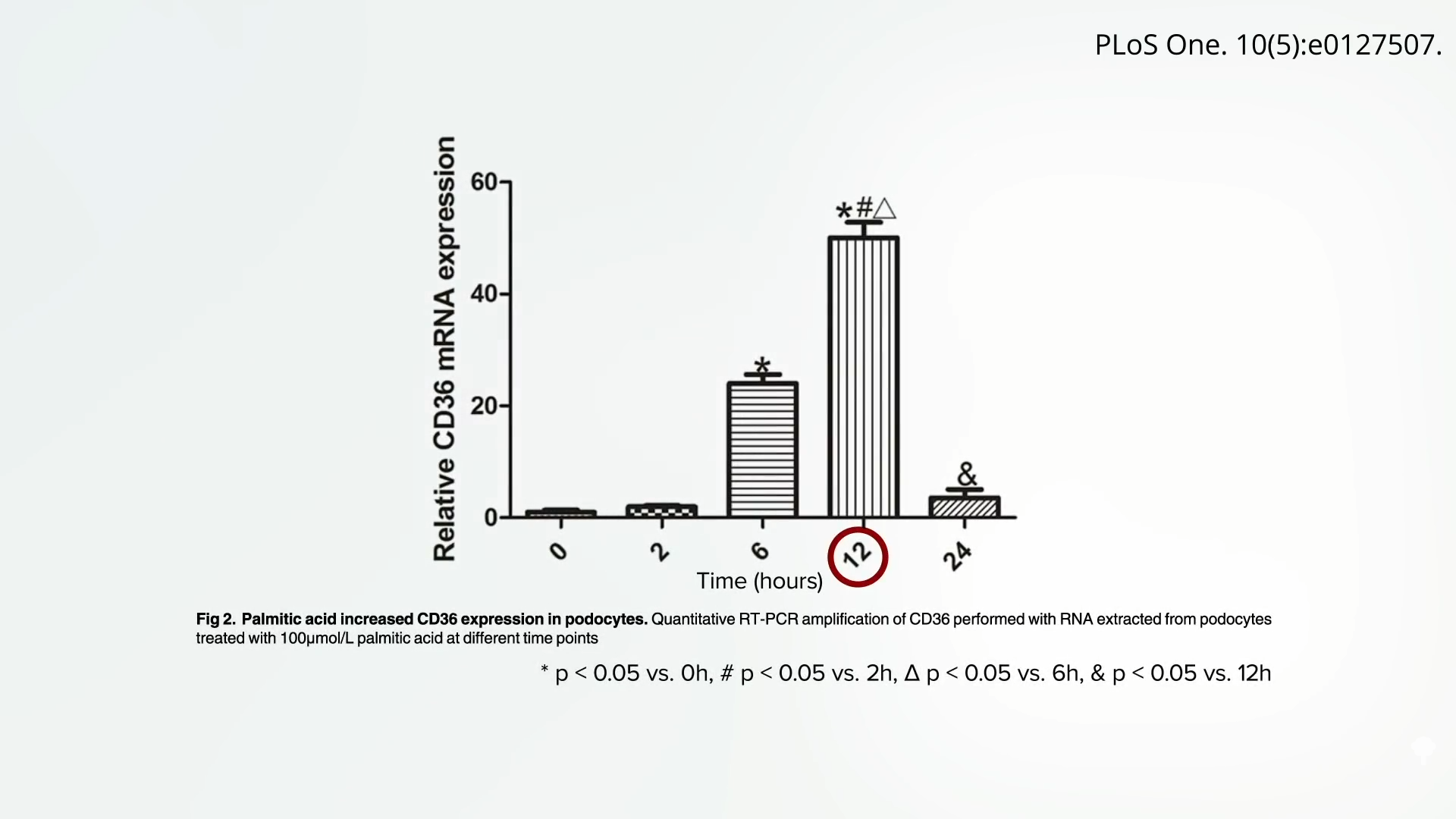

CD36 is upregulated by palmitic acid, as much as a 50-fold increase within 12 hours of consumption, as shown below and at 1:13 in my video How to Help Control Cancer Metastasis with Diet.

Palmitic acid is a saturated fat made from palm oil that can be found in junk food, but it is most concentrated in meat and dairy. This may explain why, when looking at breast cancer mortality and dietary fat, “there was no difference in risk of breast-cancer-specific death…for women in the highest versus the lowest category of total fat intake,” but there’s about a 50 percent greater likelihood of dying of breast cancer with higher intake of saturated fat. Researchers conclude: “These meta-analyses have shown that saturated fat intake negatively impacts breast cancer survival.”

This may also explain why “intake of high-fat dairy, but not low-fat dairy, was related to a higher risk of mortality after breast cancer diagnosis.” If a protein in dairy, like casein, was the problem, skim milk might be even worse, but that wasn’t the case. It’s the saturated butterfat, perhaps because it triggered that cancer-spreading mechanism induced by CD36. Women who consumed one or more daily servings of high-fat dairy had about a 50 percent higher risk of dying from breast cancer.

We see the same with dairy and its relationship to prostate cancer survival. Researchers found that “drinking high-fat milk increased the risk of dying from prostate cancer by as much as 600% in patients with localized prostate cancer. Low-fat milk was not associated with such an increase in risk.” So, it seems to be the animal fat, rather than the animal protein, and these findings are consistent with analyses from the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS) and the Physicians’ Health Study (PHS), conducted by Harvard researchers.

There is even more evidence that the fat receptor CD36 is involved. The “risk of colorectal cancer for meat consumption” increased from a doubling to an octupling—that is, the odds of getting cancer multiplied eightfold for those who carry a specific type of CD36 gene. So, “Is It Time to Give Breast Cancer Patients a Prescription for a Low-Fat Diet?” A cancer diagnosis is often referred to as a ‘teachable moment’ when patients are motivated to make changes to their lifestyle, and so provision of evidence-based guidelines is essential.”

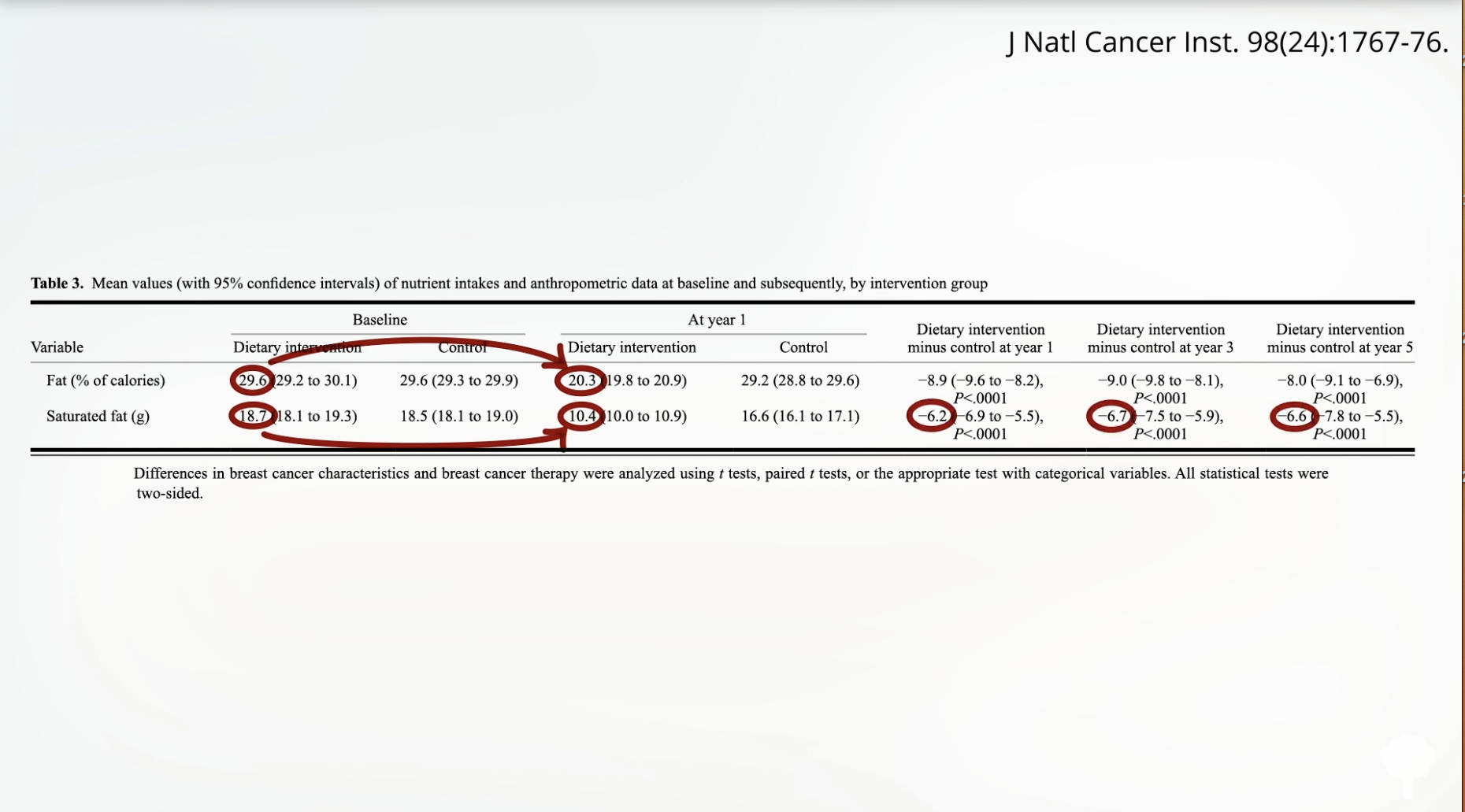

In a randomized, prospective, multicenter clinical trial, researchers set out “to test the effect of a dietary intervention designed to reduce fat intake in women with resected, early-stage breast cancer,” meaning the women had had their breast cancer surgically removed. As shown below and at 4:02 in my video, the study participants in the dietary intervention group dropped their fat intake from about 30 percent of calories down to 20 percent, reduced their saturated fat intake by about 40 percent, and maintained it for five years. “After approximately 5 years of follow-up, women in the dietary intervention group had a 24% lower risk of relapse”—a 24-percent lower risk of the cancer coming back—“than those in the control group.”

That was the WINS study, the Women’s Intervention Nutrition Study. Then there was the Women’s Health Initiative study, where, again, women were randomized to lower their fat intake down to 20 percent of calories, and, again, “those randomized to a low-fat dietary pattern had increased breast cancer overall survival. Meaning: A dietary change may be able to influence breast cancer outcome.” What’s more, not only was their breast cancer survival significantly greater, but the women also experienced a reduction in heart disease and a reduction in diabetes.

FrankLin

FrankLin