Breaking Open in the Bardo

It’s when we lose the illusion of control—a "bardo" state where we are most vulnerable and exposed—that we can discover the creative potential of our lives. The post Breaking Open in the Bardo appeared first on Lion's Roar.

It’s when we lose the illusion of control—when we’re most vulnerable and exposed—that we can discover the creative potential of our lives. Pema Khandro Rinpoche explains four essential points for understanding what it means to let go, and what is born when we do.

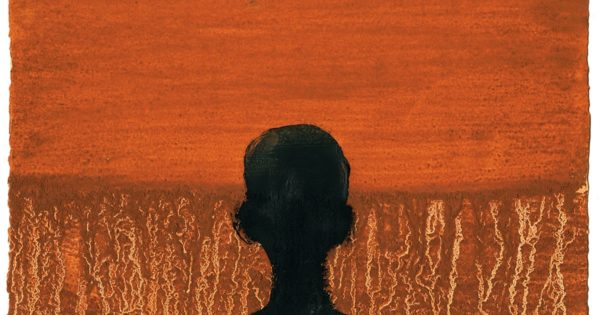

“Home & the Underworld,” by Antony Gormley, 1989. Earth, rabbit skin glue, and black pigment on paper. 28 x 38 cm.

We are always experiencing successive births and deaths. We feel the death of loved ones most acutely—there is something radical about the change in our reality. We are not given options, there is no room for negotiation, and the situation cannot be rationalized away or covered up by pretense. There is a total rupture in our who-I-am-ness, and we are forced to undergo a great and difficult transformation.

In bereavement, we come to appreciate at the deepest, most felt level exactly what it means to die while we are still alive. The Tibetan term bardo, or “intermediate state,” is not just a reference to the afterlife. It also refers more generally to these moments when gaps appear, interrupting the continuity that we otherwise project onto our lives. In American culture, we sometimes refer to this as having the rug pulled out from under us, or feeling ungrounded. These interruptions in our normal sense of certainty are what is being referred to by the term bardo. But to be precise, bardo refers to that state in which we have lost our old reality and it is no longer available to us.

Until now, we have been holding on to the idea of an inherent continuity in our lives, creating a false sense of comfort for ourselves on artificial ground. By doing so, we have been missing the very flavor of what we are.

Anyone who has experienced this kind of loss knows what it means to be disrupted, to be entombed between death and rebirth. We often label that a state of shock. In those moments, we lose our grip on the old reality and yet have no sense what a new one might be like. There is no ground, no certainty, and no reference point—there is, in a sense, no rest. This has always been the entry point in our lives for religion, because in that radical state of unreality we need profound reasoning—not just logic, but something beyond logic, something that speaks to us in a timeless, nonconceptual way. Milarepa referred to this disruption as a great marvel, singing from his cave, “The precious pot containing my riches becomes my teacher in the very moment it breaks.”

This is the Vajrayana idea behind successive deaths and rebirths, and it is the first essential point to understand: rupture. The more we learn to recognize this sense of disruption, the more willing and able we will be to let go of this notion of an inherent reality and allow that precious pot to slip out of our hands. Rupture is taking place all the time, day to day and moment to moment; in fact, as soon as we see our life in terms of these successive deaths and rebirths, we dissolve the very idea of a solid self grasping onto an inherently real life. We start to see how conditional who-I-am-ness really is, how even that does not provide reliable ground upon which to stand.

At times like this, if we can gain freedom from the eternal grasping onto who I am and how things are—our default mode—then we can get to the business of being. Until now, we have been holding on to the idea of an inherent continuity in our lives, creating a false sense of comfort for ourselves on artificial ground. By doing so, we have been missing the very flavor of what we are.

The Contrived Self

The cause of all suffering can be boiled down to grasping onto a fictional, contrived existence. But what does that mean? If we really come to understand, then there is no longer even a container to hold together our normal concepts, to make them coherent. The precious pot shatters, and all our valuables roll away like marbles on a table. Reality as we thought we knew it is disrupted; the game of contriving an ideal self is suddenly irrelevant.

This is shunyata, which gets translated in various ways, most commonly as “emptiness,” but there is no real correlate in our language, no single word or idea that can cover this ground of disrupted reality. Because “emptiness” in English has negative connotations, shunyata is sometimes translated as “voidness,” “open spaciousness,” and even “boundlessness”; Nyingmas such as Longchenpa explained emptiness in positive terms inextricably associated with presence, clarity, and compassion. But in the context of death and birth, shunyata refers to a direct experience of disruption felt at the core of our being, when there is no longer any use manufacturing artificial security.

The bardo teachings are really about recognizing the value of giving up the game, which we play without even giving it a second thought.

We’re not talking about giving up our precious human life here, of course; we’re talking about giving up on this subtle game. We hold pictures of our ideal self in an ideal world. We imagine that if we could only manipulate our circumstances or other people enough, then that ideal self could be achieved, and in the meantime, we try to pretend to have it together. It’s the game we play all the time: we keep postponing our acceptance of this moment in order to pursue reality as we think it should be.

When we suffer disruption, we find we just can’t play that game anymore. The bardo teachings are really about recognizing the value of giving up the game, which we play without even giving it a second thought. But when we are severely ill or in hospice, and we have to cede control over our own bodily functions to strangers, holding it all together is not an option.

There are times like these in our lives—such as facing death or even giving birth—when we are no longer able to manage our outer image, no longer able to suspend ourselves in pursuit of the ideal self. It’s just how it is—we’re only human beings, and in these times of crisis we just don’t have the energy to hold it all together. When things fall apart, we can only be as we are. Pretense and striving fall away, and life becomes starkly simple.

The value of such moments is this: we are shown that the game can be given up and that when it is, the emptiness that we feared, emptiness of the void, is not what is there. What is there is the bare fact of being. Simple presence remains—breathing in and out, waking up and going to sleep. The inevitability of the circumstances at hand is compelling enough that for the moment, our complexity ceases. Our compulsive manufacturing of contrived existence stops. Perhaps in that ungrounded space, we are not even comforting ourselves, not even telling ourselves everything is okay; we may be too tired to do even that. It’s just total capitulation—we’re forced into non-grasping of inherent reality. The contrived self has been emptied out along with contrived existence and the tiring treadmill of image maintenance that goes along with it. What remains is a new moment spontaneously meeting us again and again.

There is an incredible reality that opens up to us in those gaps if we just do not reject rupture. In fact, if we have some reliable idea of what is happening in that intermediate, groundless space, rupture can become rapture.

Emerging Presence

It is said that the great fourteenth-century terton in the Nyingma lineage, Karma Lingpa, soon after losing his wife and their child within just a few days of each other, extracted a treasure of teachings from the side of a mountain. Because of all the spiritual practice he had done, the disruption he experienced sparked a volcanic eruption of wisdom from which flowed The Self-Emergence of the Peaceful and Wrathful Deities from Enlightened Awareness, known here in the West as The Tibetan Book of the Dead.

If I lose all my possessions, my job, all my money, then what remains of me?

That act of revelation is in itself a key teaching, the idea that death and loss are great teachers if we can just open to the experience of profound disruption. Just like Karma Lingpa, encountering death can open us up to a basic level of being—raw, unmanaged, unmanipulated. That natural condition, that unconditioned state, is what shunyata points to.

What’s underneath all of our experience? If there is no inherent existence to hold on to, then what is ultimate reality? Even the most shallow person yearns to know this point; it’s what we’re always looking for. It’s why we fight with people we love about petty little things—because this unanswered question drives us. If we lose that fight, what’s there? What becomes of us? If we lose this relationship, what’s left? Who are we? If I lose all my possessions, my job, all my money, then what remains of me? If we don’t know the answer, then the question becomes a primordial anxiety that forms the background of all we say and do and think.

And so the third principle we can learn about death, birth, and reincarnation is this: the extent to which we know what’s underlying everything—the good, the bad, the beautiful, the ugly, that which we can control, that which we can’t—is the extent to which we can relax. To the extent that we know our presence of awareness as reality, it becomes bearable. As we gain intimacy with that ground, we can even have sanity when life is hard, even when knowing that an experience is going to be painful. Think how willing we are to bear that pain for someone we really love. It’s how life begins, after all, with our mother, through love, enduring the pain of childbirth.

Why should we be any less willing to bear the pain of death or loss or change? If we’re in touch with the ground of being, perhaps there may be ease and comfort even in dying. That ground allows us to walk the earth with a clarity that accommodates whatever arises. So when we have to lose, we can lose. And when we have to let go, at times of great loss or when we depart from this body, then something else becomes possible. This is what emerges in the bardo—presence as the ground of being.

What makes death and impermanence so painful is our idea of the strict dichotomy between existence and nonexistence. Knowing something beyond that dualism is paramount. At the moment of death, instead of being caught between the ideas of existence and nonexistence, instead of this crisis of having everything that matters to us taken away all at once, something else can open up entirely; we shift our attention to the nucleus of being, to presence itself, experiencing itself.

But when we are not in crisis, recognizing presence as our nucleus and grounding ourselves in the sense of experience itself is a difficult endeavor. The fact is that we are disassociated from our true nature. We experience it all the time—in little tastes, in the gaps between realms, between all of our many identities and roles, and even between thoughts—but since we don’t even recognize it, we don’t know how to be with it, to rest in it. We contract with our wounded sense of self and with frantic efforts to create something more ideal, more secure, more definite. In this way, we experience ourselves over and over as both confusion and wisdom—a treacherous and fantastic situation. We taste the ground here and there but can’t ingest it, which creates a dramatic friction, one that gives rise to all the mental poisons as a means of coping with this chronic cognitive dissonance between open ground and contracted being.

Confusion is the raw material of wisdom.

Without some way of managing this experience, this unsettling discontinuity punctuated by occasional disruptions to the very idea of our being, we never know if we are going to show up in the next moment as a buddha or as a demon. We’re like gods one moment, tasting the fruit of the kingdom, and hungry ghosts the next, not even able to swallow it. How confusing—and how fantastic! This confusion is the raw material of wisdom. Our path is to find presence in each of these experiences. In the case of the bardo, when presence is the only real thing left, if we are searching for security instead, wisdom can be elusive. It’s no wonder that religion becomes so poignant during times of crisis; suddenly, presence is all we are. Everything else recedes except what is right in front of us. Recognizing this opens up the potential to experience life with awareness of impermanence and the presence it illuminates.

So the first essential point is rupture. The second is emptying out the contrived self. And the third is the recognition that our experience is based on dynamic, responsive presence. Our goal as vajra yogins and yoginis is to know that ground, become familiar with it, and learn to relax into the inherent peacefulness of not knowing what comes next. When we do—and to the extent that we do—everything changes. We are no longer slaves to primordial anxiety.

Experiencing a loss can be freeing. When we are free of all our psychological heaviness, the accumulated weight of our usual momentum, we have an opportunity to know the raw presence that remains. To be a Buddhist is to dedicate our lives to abiding in that impermanent, empty, visceral presence. We can bear with greater ease those losses that we know we will inevitably face, because we identify with the thread of wakefulness that we meet in all of them. And then perhaps, when death draws near, we can relax with ease into the ground of being as we shed this skin, finally let go of this body, and experience liberation—undefended being in groundless space.

The Play of Experience

Longchenpa described the fourth essential point as “majestic utter sameness—the pure fact of being, where mind and what appears are primordially pure.”

The fourth essential point, put simply, is that the world we produce from loss can be created with a light heart as a state of play. Thinley Norbu Rinpoche wrote, “Fish play in the water. Birds play in the sky. Ordinary beings play on earth. Sublime beings play in display.” In the raw, broken-open state, this place where we let go of all games, there is actually a great sense of relief available to us, a knowledge that we don’t have to do that anymore, to be that. When someone dies, don’t we suddenly see how unreal so many things are and how visceral the present space is? There can be a feeling of getting to the heart of things, a juxtaposition of real and unreal. That’s the beauty of not grasping onto an inherent reality. If we can find ways to disrupt our own habit of clinging to our continuity story, to just strip it all down—without having to wait to lose a loved one, or get that terminal diagnosis from our doctor, or lie on that gurney—then what we find there in any bare moment is creative, instantaneous playfulness. It is this raw energy that spoke directly to Longchenpa: “All that is has me—universal creativity, pure and total presence—as its root. How things appear is my being. How things arise is my manifestation.”

Impermanence is not just an illuminator of loss. It is an illuminator of newness, the ever-unfolding present moment and its creativity.

Emerging from the bardo, we reenter the flow of life with a new sense of groundlessness: it is clear that “later” is not always a luxury that will be available to us; we are also disconnected from the past. That makes nowness starkly available. The perspective gained in the bardo cuts through petty concerns. It cuts through delusions so that whatever we contact, we do so with a raw presence, without the denial of impermanence. As long as we remain in this illumined state and still remember that grasping is futile, a new kind of openness becomes available to us. We have lost our delusions; to love and live now is to do so with nothing to lose because, for the time being, what really mattered has already been lost.

The Vajrayana idea of death, birth, and reincarnation is not just a matter of preparing for physical death, or dealing with the loss of our loved ones with rituals and prayers, or having the right attitude in mourning and grief. It is the messenger of our own uncontrived being, delivering us into the basic space of pure being. It shows us what comes after rupture. What may be the most poignant thing about the loss of a loved one is that after they have passed away, life simply keeps going. It just keeps going.

Death is connected to rebirth. The rupture of bardo inevitably leads to whatever is next. If we appreciate these successive deaths and rebirths in our lives, then we can value the bardo for what it is—the pause that makes movement apparent, the silence that makes all sounds more vivid, the end that clarifies what exactly we will now be beginning. Impermanence is not just an illuminator of loss. It is an illuminator of newness, the ever-unfolding present moment and its creativity.

Traditionally, we have three different possibilities for what happens after death. There is the default mode of rebirth with all these accumulated, bulky layers of previous karmic propensities. There is also the kind of reincarnation that great compassionate beings, such as the Dalai Lama and the Karmapa, consciously choose for the highest benefit of sentient beings in this world. But then there is something else: this more impersonal, ceaseless creativity that keeps multiplying itself in playful modes of being, like the image from the Avatamsaka Sutra of a radiant buddha oozing buddhas from every pore of his or her being, and from every pore of every one of those buddhas, more buddhas giving way to whole other universes of being. This is true compassion, a total responsiveness to what is here.

That’s the kind of life after death that Vajrayana practitioners rehearse in deity yoga. It is a practice of dying to the contrived self in order to arise in the creative space of momentary presence. It is bursting forward into life, emerging with this pure primordial creativity at play in the shifting fields of empty identities. It’s a kind of regeneration, a total recycling, a complete merging and reemerging.

It is a shifting ground, because compassionate responsiveness is not static; we never step into the same river twice. But this doesn’t mean that there is nothing there. It isn’t that there is something there, either—but it’s not nothing. Longchenpa calls it the “self-originating clear light” and says that in this light, “what appears is neither concretized nor latched onto, because what appears never becomes what it seems to be and is intrinsically free.” You see? It is not just another construct. It’s the ground that does not need to be contrived or maintained. It’s experience itself.

UsenB

UsenB